Chris Dawson Case Note

How effective is the media as a non-legal measure in achieving justice? Conversely, what are the risks and challenges that the media may pose to existing legal measures used by police and courts? How does the legal system ensure that the rights of the victim, alleged offender and society are all met?

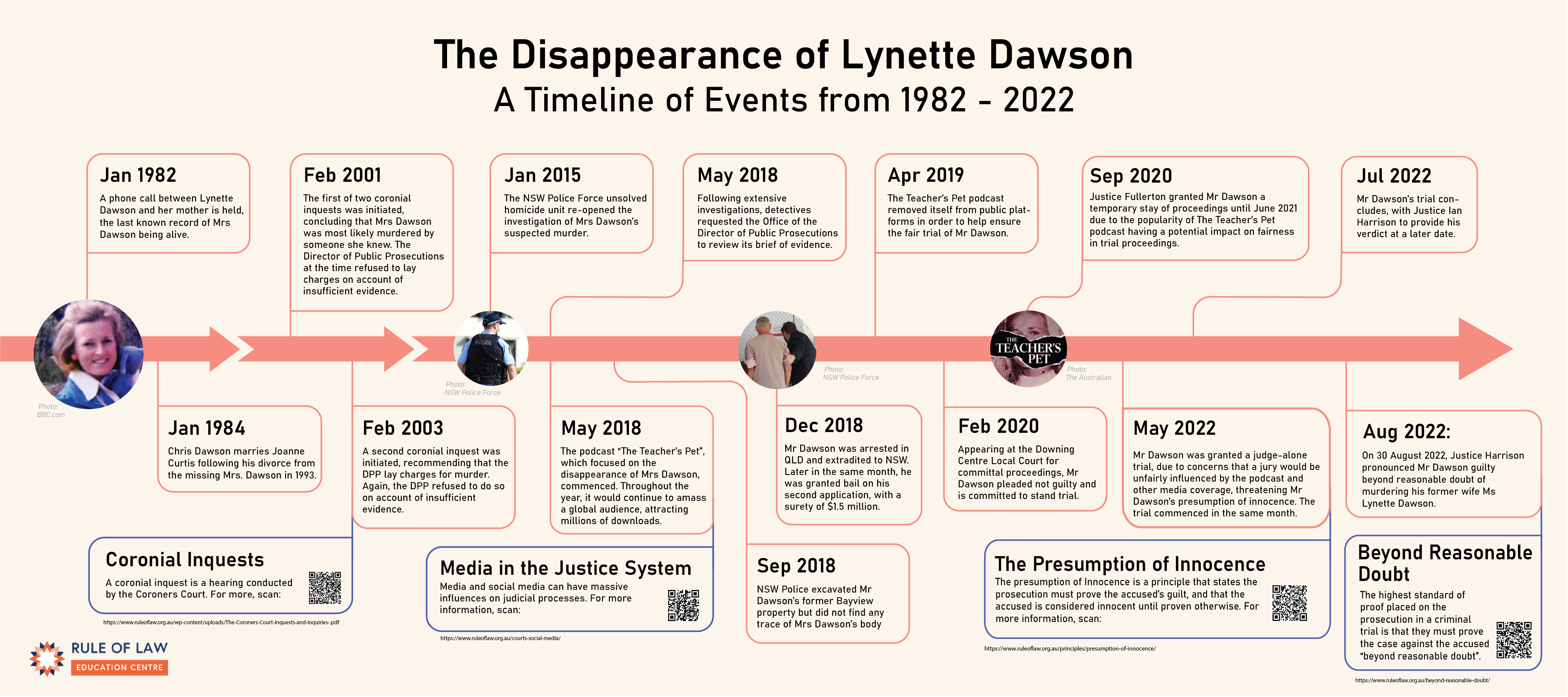

These questions were relevant in the case surrounding Lynette Dawson, whose sudden disappearance was the centre of a sporadically open forty-year investigation, as well as the subject of the globally acclaimed podcast ‘The Teacher’s Pet.’

The podcast recounted the events leading up to and following Lynette’s disappearance, strongly suggesting that her husband, Chris Dawson (Dawson), was her murderer. With Dawson’s trial commencing in 2018, the year that the podcast topped the charts in Australia, New Zealand, the UK and Canada, the courts faced new challenges in ensuring Dawson’s presumption of innocence would be preserved. In many ways, this case demonstrated the mechanisms that the judicial process has in place to ensure a fair trial is achieved in cases of extraordinary public exposure and sensitivity.

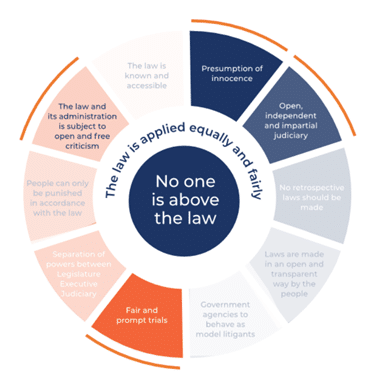

The presumption of innocence and the achievement of fair and prompt trials are principles of the rule of law. Click here to find out more

Courts and investigative bodies were met with complications in locating and acquiring evidence, partially because the disappearance of Lynette Dawson had occurred four decades prior. This resulted in the courts having to rely on circumstantial evidence.

Following Dawson’s trial, law reforms were passed through NSW Parliament in October 2022. New ‘no body, no parole’ legislation was adopted to ensure that similar future outcomes would support the rights of the victim’s family and friends.

This case note should be read together with: “Chris Dawson Trial and the Role of Media”

Case Citations

Trial Judgement: R v Dawson [2022] NSWSC 1131 (30 August 2022)

Stay of Proceedings Application: R v Dawson [2020] NSWSC 1221 (11 September 2020)

Judge-alone Application: R v Dawson [2022] NSWSC 552 (09 May 2022)

Click to Jump to Section

Facts of the case

Chris and Lynette Dawson met at a highschool function in 1965, both being 16 at the time. Five years later, the two married and raised two daughters. Dawson became a reasonably well-known and respected rugby league player and teacher within his community.

In 1980, Dawson initiated an affair with a 16-year-old student, JC, while working as a teacher in the Northern Beaches of Sydney. Over the next few years, tensions rose between Dawson and his wife, especially after JC had briefly moved in with the Dawson family in October of 1981, and Lynette discovered they were sleeping together while she was in the house. Multiple witnesses recounted evidence of Dawson committing acts of physical violence against Lynette during this period. In December of 1981, Dawson briefly left the home to be with JC, and returned to the home on Boxing Day. In January of 1982, Lynette’s co-workers witnessed more bruising, and she confides that she and Dawson were going to attend marriage counselling, which they did on January 8.

Lynette Dawson, 33, was last heard from on January 8, 1982, seemingly leaving her family and possessions behind. During his trial, Dawson claimed that Lynette left home, and he had shared phone calls with her after she had left, although the court would later conclude that this was untrue.

Dawson reported his wife’s disappearance to the police six weeks later, after being begged by Lynette’s mother, Helena. The incident would not be investigated for years due to the NSW Police’s insistence that there were no suspicious circumstances.

Dawson married JC in 1984 and the couple moved to the Gold Coast in Queensland. After a string of domestic violence incidents which caused JC to ‘fear for her life,’ the couple divorced in 1990. In the same year, Dawson met his third and current wife, Susan Dawson, while working as a casual teacher in Queensland.

Investigative History

During the first few years after Lynette’s disappearance was reported, no investigations were undertaken. She was deemed a missing person by the authorities who claimed that there was no reason to believe that her disappearance was suspicious, particularly as family friends had reported seeing her in public a week after her disappearance on the NSW Central Coast. They accepted Dawson’s accounts that she had left home.

In 1990, after continuous requests from Lynette’s family and friends, the police began to investigate Lynette’s disappearance. Police conducted a ground survey of the couple’s former Bayview home using radar technology, but nothing was found.

The case was reopened and handed to Detective Damien Loone in 1998, but because the police records had been ‘poorly’ compiled and stored, the investigation effectively had to start over. Dawson declined to be interviewed by investigators in 1999, and in 2000, police conducted a small excavation at the Bayview house, focusing on the pool surrounds. A cardigan was found but is not connected to Lynette.

In February of 2001, the first of two coronial inquests were initiated after investigations from the NSW Police remained inconclusive, with Deputy State Coroner Jan Stevenson determining that Lynette was most likely murdered by a ‘known person’. The Director of Public Prosecutions at the time did not lay charges on account of insufficient evidence.

In February of 2003, a second coronial inquest began, with Deputy State Coroner Carl Milovanovich recommending that the DPP lay charges for murder by a known person. Again, the DPP refused to do so, announcing there was ‘insufficient evidence to support any criminal charge against any person.’ The police were intermittently silent on the incident for the next 12 years until, in 2015, the NSW Police Force Unsolved Homicide Unit, led by Detective Daniel Poole, reopened the investigation of Lynette’s suspected murder.

Over the next three years, the incident was under extensive investigation, with detectives requesting the DPP review their brief of evidence. In September of 2018, the Dawsons’ former Bayview property was mapped, searched, and excavated, though no evidence could be recovered. In addition, in 2018, the podcast ‘The Teacher’s Pet’ commenced, which focused on the disappearance of Lynette Dawson. It was produced by investigative journalist Hedley Thomas of the Australian Newspaper. Throughout the year, it would continue to amass a global audience, attracting millions of downloads. Its popularity incited greater public interest in the case, allowed Lynette’s family and friends a platform from which to be heard, and invited witnesses to come forth and provide their testimonies.

Dawson was arrested in QLD on December 5, 2018 and charged with his former wife’s murder. He was extradited to NSW for further proceedings.

‘The Teacher’s Pet,’ which centred around the history of the Dawson case, was one of Australia’s most successful podcasts. Click here to find out more.

Procedural History

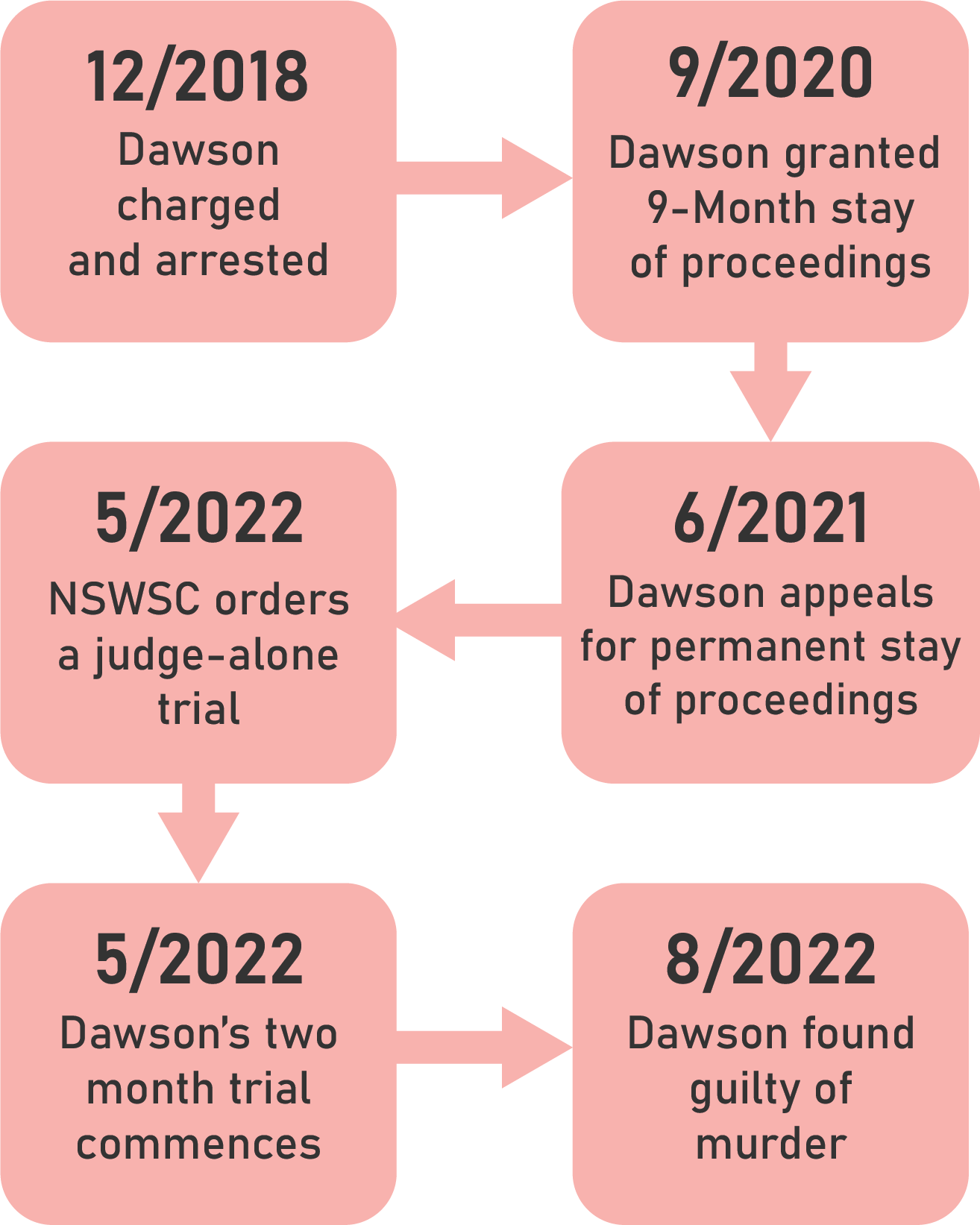

Following Dawson’s arrest in 2018, he submitted two bail applications and after the first of which was rejected, the second application was granted with a surety of $1.5m.

In his committal proceedings during February 2020, Dawson was committed to stand trial after pleading ‘not guilty’ to the charge of Lynette’s murder. At the time, his trial was set to be heard later in 2020.

However, due to the mounting popularity of ‘The Teacher’s Pet’ podcast, Dawson applied for a permanent stay of proceedings. This would have indefinitely stopped the case from continuing, on the grounds of the podcast disrupting the impartiality of a potential jury. He also claimed that the podcast ‘eroded his fundamental right to the presumption of innocence and his right to silence.’

Supreme Court Justice Fullerton rejected Dawson’s application for a permanent stay of proceedings, reasoning that the consequences of the podcast did not ‘outweigh the considerable public interest in the continuation of a trial.’ However, she granted him a temporary stay of proceedings of nine months to relieve the concerns of fairness sparked by the podcast.

Dawson’s trial was further delayed as he appealed the Supreme Court’s decision, bringing the matter to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal. In June 2021, the appeal was dismissed on the grounds that a permanent stay of proceedings should only be allowed for the ‘most extreme cases,’ which Dawson’s case did not qualify.

Dawson then attempted to appeal to the High Court of Australia but was refused to do so, Dawson’s trial was rescheduled to commence on 9 May 2022.

In May 2022, Dawson made an application for his trial to be heard by a judge without the presence of a jury. Known as a ‘judge-alone trial’, such trials are used to limit the threat of biased jurors endangering the fairness of his trial. This application was granted by Supreme Court Justice Beech-Jones and on 9 May 2022, his trial commenced as scheduled.

Dawson’s trial was heard by Justice Ian Harrison (Harrison J) and concluded in July of 2022. On the 31st of August 2022, Harrison J pronounced his verdict that Dawson was guilty of murdering his wife Lynette on or soon after January 8, 1982.

Media and the Rule of Law

The substantial influence the podcast ‘The Teacher’s Pet’ had on Chris Dawson’s judicial process makes clear the potential impact the media can have on solving ‘cold cases’. However, there are risks and benefits of media involvement within the justice system and in achieving the rule of law.

In its interaction with the judicial process, the role of the media is to act as a link between the courts and the people, while remaining compliant with the rules of the court in their commentary, so as not to harm the presumption of innocence of the accused.

The presumption of innocence imposes on the prosecution the burden of proving the charge and guaranteeing that no guilt can be presumed until the charge has been proven.

Learn more here.

How did The Teacher’s Pet achieve open justice?

One of the roles the media should aim to play is to be a facilitator of open justice. The key functions of open justice are:

- to inform the public of what is happening in the courts and how justice is being administered.

- to expose participants to public scrutiny enhancing truthfulness and ensure accountability of the courts for the decisions made.

- to provide public vindication for relevant parties and the community (the ‘therapeutic function’).

Regarding the first function, Thomas’ podcast brought the largely unknown circumstances of Lynette Dawson’s disappearance to the attention of the nation, as well as asserting that because it had been deemed a ‘cold case’ by the authorities, justice would likely never be achieved.

In doing so, the podcast fulfilled the second function of open justice by holding the relevant parties accountable. For example, in episode 8 of ‘The Teacher’s Pet’, Thomas scrutinised the conduct of some police officers and detectives throughout the history of the case.

The podcast’s success then allowed it to also achieve the third function of open justice in a direct and substantial way, by generating a massive amount of public interest, influencing the NSW police to prioritise the re-opening of the case.

Thus, considering that the disappearance of Lynette Dawson was a ‘cold case’ that was no longer being investigated by authorities, it may be conceivable that if not for Thomas’ podcast, Lynette Dawson and her family would not have received an outcome through the legal system.

The media plays an important role in the legal landscape. It has the power to provide scrutiny, accountability and transparency of legal processes. View our resources on media here.

Did The Teacher’s Pet obstruct the administration of justice?

Thomas’ ‘The Teacher’s Pet’ served as a platform that not only presented the facts of the case, but also voiced personal speculations and suspicions of Thomas, backed by statements from legal experts and comments from prior judges. The series was underpinned by Thomas’ belief that ‘Chris Dawson was responsible for Lyn’s disappearance.’ With such a strong stance reaching such a wide audience, it poses the question as to whether the podcast was fulfilling its role in assisting the administration of justice, or alternatively, obstructing justice by removing Dawson’s presumption of innocence.

The presumption of innocence is a principle central to the rule of law, which states that everyone should be regarded as innocent until they have been proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt. As Dawson had not yet been tried, was it fair, correct, or even lawful for the podcast to take such a conclusive stance on Dawson’s guilt?

Sub-judice contempt, or contempt of court, is an offence under the Local Court Act 2007 s 24 and involves conduct that interferes with or undermines the authority or performance of the courts. This law protects proceedings that are current or pending (UNSW Law Journal, 1987).

Thomas’ podcast was focused on a cold case with no proceedings pending or on appeal. ‘Thomas’s work did not interfere with criminal proceedings because there were no criminal proceedings’ (Chris Merritt, 2022). Therefore, Thomas was not in violation of the law of sub-judice contempt. (He could, however, have been at risk of defamation proceedings.)

In the interests of maintaining a fair trial for Dawson, Thomas voluntarily removed the podcast from all platforms in April of 2019. However, the popularity of the podcast had already spread in influence, resulting in some challenges regarding the fairness and promptness of Dawson’s trial.

Fair and Prompt Trials

One of the principles of the rule of law is that trials should be both fair and prompt. In the 40-year timeframe between Lynette Dawson’s disappearance and Chris Dawson’s verdict being handed down, promptness was compromised on several occasions to maintain fairness for the accused.

All people have the right to a fair and prompt trial, on the basis that all citizens are considered equal before the law. Learn more about fair and prompt trials here.

Stay of Proceedings

A stay of proceedings is a power of the courts contained within s 67 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005, allowing for the court to permanently or temporarily halt proceedings if a trial would be ‘clearly inappropriate’, or if there had been an abuse of process (Mondaq, 2022). The stay would have to be applied for by the defendant and accepted by the court.

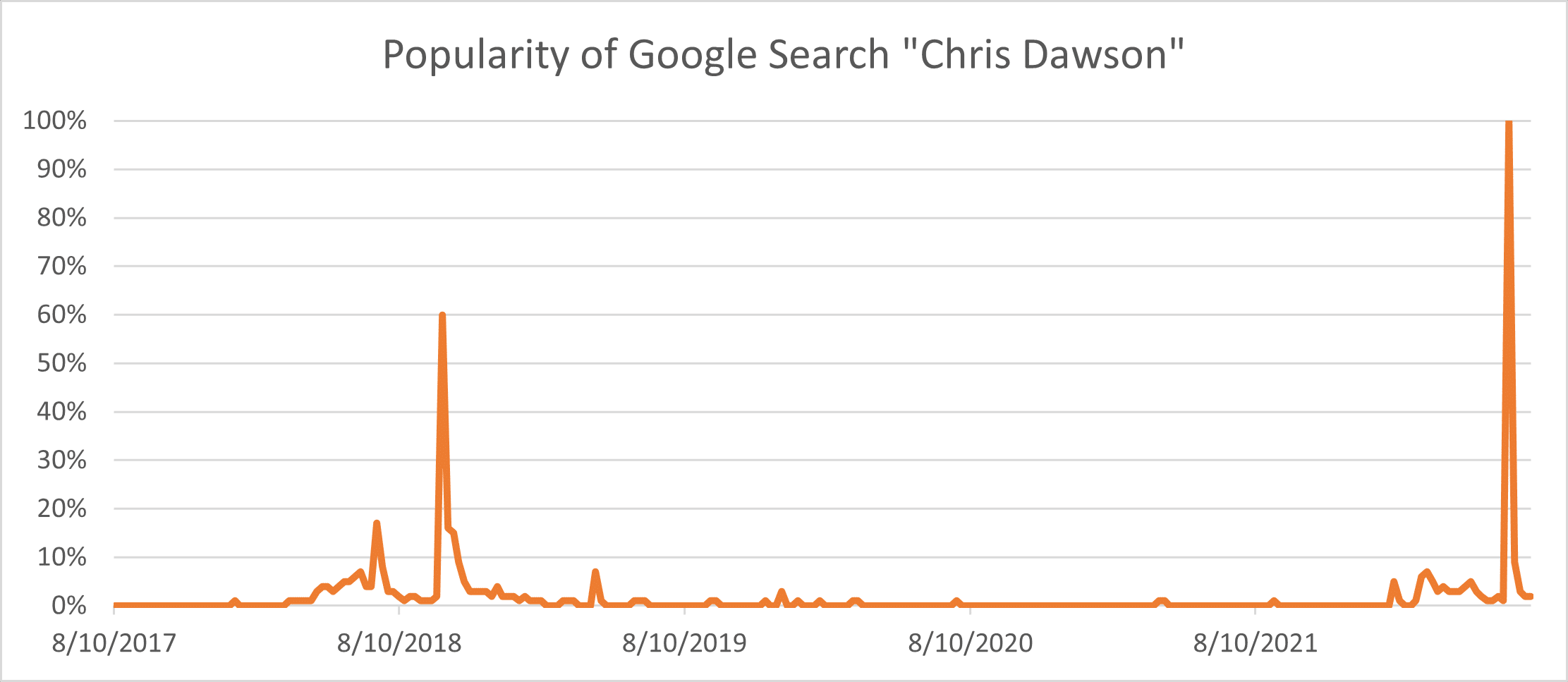

In Dawson’s case, the nine-month stay of proceedings was granted to relieve concerns that the overwhelming publicity of the case would incite prejudice against him, providing a greater opportunity for a fair trial. This temporary ‘pause’ in Dawson’s court proceedings, in conjunction with the removal of the Teacher’s Pet podcast from all streaming services, resulted in a gradual decline of public discourse surrounding the case.

This could be evidenced by the following data from Google Trends, illustrating the popularity of the Google search for “Chris Dawson” in Australia, with the two spikes occurring in December 2018, with the growth of the podcast, and again in September 2022, during Dawson’s trial:

Judge-alone Trials

When an indictable criminal offence proceeds to trial in NSW, evidence is typically presented to a judge and a jury of 12 people. The jury, complying with the directions of the judge, serves the role of deciding matters of fact based on the evidence they have heard in court. The right to a trial by jury in Federal matters is contained within s 80 of the Australian Constitution, ensuring that the community is represented in the administration of justice.

However, this may not always be the best avenue for achieving justice. In some cases, the jury may be consciously or unconsciously prejudiced against the defendant based on:

- The shocking or repulsive nature of the allegation;

- The personal prejudicial opinions of jurors;

- The possibility that jurors may become impatient with long-running cases and fail to follow due process; or

- Any pre-trial media publicity that may have influenced the jury.

Because of these factors, it may be in the interests of justice for the case to be heard only by a judge, minimising the risk of jury bias. To that end, s 132 of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 stipulates that:

- An accused person or the prosecutor in criminal proceedings in the Supreme Court or District court may apply to the court for an order that the accused person be tried by a judge alone (a “trial by judge order”).

- The court must make a trial by judge order if both the accused person and the prosecutor agree to the accused person being tried by a Judge alone.

Dawson asserted that the popularity of the podcast threatened the impartiality of the jury to such an extent that even after the nine-month stay of proceedings granted by the Supreme Court, the potential for a jury to be influenced by the media was still too great. After the prosecution came to an agreement, the order was made to have the trial heard without a jury.

The option of holding a ‘judge alone’ trial is another example of the legal measures that the courts have in place to achieve fairness and a just outcome for the accused. Moreover, there was the added benefit in this case of improving the promptness of the trial, as the order would ‘significantly reduce the length of the hearing’ compared to a jury trial. This is because a jury trial involves the judge needing to take additional care to give directions to the jury, as well as providing time for the jurors to deliberate.

Importantly, Harrison J gave detailed reasoning for his decision of returning a guilty verdict, which would not have happened in a jury trial. Along with the court’s public livestream of the judgement which attracted 25,000 viewers, the courts ensured that open and transparent justice was upheld. Therefore, public confidence in the legal system could be maintained.

Evidence

In court proceedings, evidence is needed to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt. Only then can a verdict of guilt be established.

https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1995-025Significant Forensic Disadvantage

Significant Forensic Disadvantage

‘Significant forensic disadvantage’ was a term that was frequently used throughout Dawson’s trial and, according to s 165B of the Evidence Act 1995, refers to:

- the fact that any potential witnesses have died or are not able to be located, or

- the fact that any potential evidence has been lost or is otherwise unavailable.

These two factors contributed greatly to what made the case so difficult to decide, both resulting from ‘the extraordinary delay between 8 January 1982 when the Crown alleges Dawson killed his wife and 9 May 2022 when his trial commenced.’

Throughout the 40-year period of the case, 12 witnesses that contributed evidence to the case in some way had died. This left many loose ends in the case, as the court could not test the validity of their previous claims, or ask them for additional detail.

Moreover, many articles of evidence that would have provided clarity to some of the court’s points of contention were lost or made unavailable over the years. This included telephone records, employee information from Lynette’s workplace, bank statements and often, people’s memories.

S 165B of the Evidence Act 1995 requires that when a significant forensic disadvantage has been identified by the court, the judge and jury (in this case, just the judge) needs ‘to take that disadvantage into account when considering the evidence.’

In a case such as Dawson’s in which evidence was so sparce and rarely reliable, it is important that court considers evidence circumstantially.

Circumstantial evidence

In cases where there is not enough direct evidence available to secure a conviction beyond reasonable doubt, the case is said to be circumstantial. The Crown must form their case around circumstantial evidence, that is, evidence that does not prove a fact directly, but rather ‘points to its existence.’

On the surface, the consideration of circumstantial evidence may appear less reliable or ‘concrete’ than direct evidence, and thus, might seem unfair to the Defendant. However, circumstantial evidence and direct evidence are not treated the same way when the judge is weighing up their verdict.

In a circumstantial case, the judge must use all relevant circumstances known to the court as a whole to form their judgement. This could include, among other factors:

- The relationship and history between the defendant and the victim,

- Any possible motives that could be inferred,

- Any other actions or statements made by the defendant that could indicate their guilt.

By comparison, direct evidence, such as the defendant’s fingerprints on a weapon, can be considered independently in order to come to a guilty verdict.

In Dawson, the Crown presented many pieces of circumstantial evidence to the court, including:

- Witness reports of Dawson committing acts of domestic violence against Lynette;

- The deterioration of Dawson’s marriage with Lynette;

- Dawson’s affair and infatuation with JC providing an inferable motive for Lynette’s murder;

- Witness accounts of Dawson’s ‘violent, aggressive and controlling behaviour’; and

- The unlikelihood of Lynette disappearing of her own will, leaving her children, financial access, and possessions behind.

The last of the circumstantial grounds listed above was accepted by Harrison as ‘a most compelling body of evidence’ in confirming Lynette’s death, considering that such an act would be entirely inconsistent with her character and relationship with her children.

Other pieces of evidence, such as witness recounts of seeing Lynette in passing after her disappearance, were rejected by Harrison J on the grounds that they lacked sufficient reliability or feasibility. These recounts included sightings of Lynette from afar, in a crowd, or only for a brief moment.

In his verdict, Harrison J stated that:

‘The circumstantial evidence in this case, considered as a whole, is persuasive and compelling. None of the circumstances considered alone can establish Mr Dawson’s guilt but when regard is had to their combined force I am left in no doubt… I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that [Dawson’s murder of Lynette is] the only rational inference.’ [R v Dawson [2022] NSWSC 1131].

Post-trial Law Reform

Following the trial, questions regarding the circumstances of Lynette Dawson’s murder and the current whereabouts of her body remained unanswered. The Dawson case inspired a public push for law reform in NSW, seeking a way to enforce the truthful disclosure of a victim’s remains from a convicted homicide offender.

A petition calling for a ‘no body, no parole’ law to be passed in NSW (as it has been in other states and territories) gained enormous public support, earning over 30,000 signatures. The law was proposed and subsequently passed through State Parliament on the 13th of October 2022 as an amendment of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences Act) 1999.

Under s 135 A, it requires that a ‘parole order must not be made where offender has not cooperated in locating victim’s body or remains.’

Minister for Corrections Geoff Lee said the new legislation is ‘about doing right by families and bringing them closure… The law is just and it is fair and it gives victims dignity and respect.’

To that end, this reform considers the rights of the victim’s families and friends through the enforcement of post-sentencing considerations. Dawson is scheduled to be sentenced on the 21st of November 2022.

Sentencing

On the 2nd of December 2022, Justice Harrison sentenced Chris Dawson to a maximum of 24 years in prison for the murder of his wife Lynette, with a non-parole period of 18 years. Justice Harrison asserts that the severity of this sentence is proportional to the crime committed by Chris Dawson, which he stated was “objectively very serious”. The following sentencing considerations were taken into account by Justice Harrison.

Aggravating Factors

Dawson has not admitted guilt or remorse for his offence, which constitutes an aggravating factor under the Crimes (Sentencing and Procedure) Act 1999 (CSPA), s 21A 2. Furthermore, the fact that Lynette Dawson’s body has never been located or recovered is an aggravating circumstance of the offence of murder, extending Dawson’s total sentence and his non-parole period.

Objective Seriousness

The objective seriousness of a crime is one of the foremost considerations when forming its sentence. To this end, Justice Harrison stated that Lynette was ‘unsuspecting,’ ‘faultless and undeserving of her fate’ and that Dawson’s motives for the murder were ‘selfish and cynical.’ The severity of the offence is amplified when considering its impact on Lynette’s family, friends and community, particularly regarding the fact that her murder deprived her two daughters of a mother during their childhood. Both of Lynette’s siblings, as well as one of her daughters, submitted their victim impact statements to the courts, which detailed the ‘injury, emotional harm and loss’ they had suffered as a result of Lynette’s murder. The rules surrounding the use of victim impact statements as considerations for sentencing are contained within s 28 of the CSPA.

Delay

The lengthy delay between an offender’s crime and their sentence may be a sentencing consideration under common law (R v Blanco, 1999). Justice Harrison contended that ‘Mr Dawson has enjoyed 36 years in the community unimpeded by the taint of a conviction for killing his wife or by any punishment for doing so.’ Moreover, his denial of responsibility for Lynette’s murder had provided him with the practical benefit of allowing him to remarry to JC and start a new family. As a result, Justice Harrison stated that he was ‘unable to accept that Mr Dawson can legitimately embrace the alleged burdens of any delay without simultaneously being required to accept the benefits.’

Mitigating Factors

Dawson had no record of previous convictions and according to several testimonials from his family, he is a ‘loving father, a doting grandfather and a loving and loyal husband,’ indicating evidence of his ‘good character,’ a mitigating factor contained within s 21A 3. Justice Harrison also stated his belief that Dawson has good prospects for rehabilitation, though due to his low prospects of living past his imprisonment sentence, ‘the significance of that conclusion, in this case, is necessarily reduced.’

Age

One of the complicating factors in the sentencing of this case is Dawson’s age. As of his sentencing date, Dawson is 74 years old, meaning he will be 92 by the time he is allowed parole, on account of the recent ‘no body, no parole’ laws passed in NSW. Justice Harrison stated in his handing down of Dawson’s sentence that ‘the reality is he will not live to reach the end of his non-parole period, or will alternatively, by reason of his deteriorating cognitive condition and physical capacity, become seriously disabled before then even if he does.’

Justice Harrison recognised in his judgement that Dawson would find imprisonment more difficult than most inmates on account of his age and health conditions, as well as the ‘unavoidable prospect is that Mr Dawson will probably die in jail.’ Relevantly, his age renders him ‘highly unlikely’ to re-offend. Despite this, he claimed that he is still required to impose a sentence that satisfies the community’s expectations of punishment, retribution and denunciation, which reflects the objective seriousness of Dawson’s offence. While an offender’s old age can be considered a mitigating sentencing factor under statute and common law, it is not a strict requirement and Justice Harrison chose not to grant leniency in this case because of it.

Media Attention

Dawson argued that the intense global media scrutiny following his arrest and trial had been so persistent that he had already faced punishment at a level beyond what he should expect for his conviction, and that his jail sentence should be reduced accordingly. Further, because of the infamy of his case, he faces regular ‘vilification’ and threats of violence from other inmates, which he stated should be accounted for in the severity of his sentence. Nevertheless, Justice Harrison concluded that ‘Mr Dawson is now the author of his own misfortune,’ and to grant him any degree of leniency for the media attention he attracted would be inconsistent with the purpose of sentencing to denounce criminal behaviour according to the views of society.

Sentencing Activity

Wayne Gleeson, Founding Member of the Legal Studies Association and member of the NSW Sentencing Council has written this exercise for students regarding the Dawson Sentencing. This resource was written before Dawson’s sentence was handed down, and asks students to determine an appropriate sentence for Chris Dawson. It is best if this activity is done before students know what sentence Justice Harrison imposed.

Conclusion

The case of Chris and Lynette Dawson was extraordinary from a legal perspective, displaying the effectiveness of the measures in place that seek to secure justice for victims and their families, while at the same time, preserving the rights of alleged offenders.

The non-legal response of the media, particularly ‘The Teacher’s Pet’ podcast, successfully fulfilled its role as a facilitator of open justice between the courts and the community, although at the cost of causing further delays. It is important to reflect that the podcast was only legally permissible because it centred around a case which had been suspended for a considerable length of time. Had the podcast focused on an actively ongoing case, it may have been in breach of sub-judice contempt.

The overwhelming public attention stirred by the podcast compelled the courts to take some legal measures of their own, such as the temporary stay order and the judge-alone order, which were intended as a means of balancing the importance of fairness and promptness.

Unfortunately, the Dawson case also highlighted some failings of the criminal investigation process and its administration. The 40-year long delay between Lynette’s death and the case’s resolution left her family and close friends without justice for an unnecessarily extensive period, during which time, most of the evidence that could have been conclusive was rendered unusable.

The Dawson case serves as a ground-breaking case that emphasises the need for the media and courts to work together to achieve justice through the cooperation of legal and non-legal means. This is especially true in the present age, as media reach grows and becomes an increasingly universal part of our day-to-day lives through technological advances in communication, such as social media and podcasts.

Additional Matter

Following his conviction for the murder of Lynette, Chris Dawson was charged with one count of ‘carnal knowledge by a teacher’. This is the charge that existed under s73 of the Crimes Act in 1980, specifically for fathers, step-fathers or teachers having sex with a young person between the ages of 10 and 17, when the offences were alleged to have taken place.

In the NSW legal system, offenders facing historical offence charges must be charged and tried under the law that prevailed at the time of alleged offences. This practice supports fairness for the accused as the offender is facing punishment that would be reflective of the moral and ethical standards of the time that the offence was committed. This means their actions would be judged in the context of what was considered reasonable behaviour by society’s standards at that time.

Given the vast amounts of publicity surrounding the initial release and subsequent re-release of the podcast “The Teacher’s Pet” and his murder trial, this matter was conducted as judge alone trial in the NSW District Court to protect the presumption of innocence and provide Mr Dawson a fair trial.

Judge Sarah Huggett found Mr Dawson guilty on June 28, 2023 and sentenced him to 3 years imprisonment, with a non-parole period of two years.

The Dawson case serves as a ground-breaking case that emphasises the need for the media and courts to work together to achieve justice through the cooperation of legal and non-legal means. This is especially true in the present age, as media reach grows and becomes an increasingly universal part of our day-to-day lives through technological advances in communication, such as social media and podcasts.

Appeal Against Conviction – Dawson v R [2024] NSWCCA 98

In NSW, appeals to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal (NSWCCA) can only be made on points of law, the sentence or the conviction itself. On May 13 2024, Dawson appealed his conviction of murder using the following reasons:

- 1 appeal on a point of law: Under s165b of the Evidence Act, judges are required to inform juries of the potential ‘significant forensic disadvantage’ an accused person may be subject to due to delayed prosecution, and the need to take into account that disadvantage when considering a verdict. If there is no jury, judges must take this into account.

Significant forensic disadvantage is the case where evidence may be reduced in quality due to the time that has lapsed since the commission of the crime in question, and therefore may make the accused subject to a disadvantage as the evidence is either not able to be properly tested before the court, or the quality of the evidence is not as high as it may have been closer to the commission of the crime. Among other instances, significant forensic disadvantage can arise in circumstances where a witness has died, there is an inability to locate witnesses, physical evidence is lost, has deteriorated or is not available for use any longer, or there may be a distortion of facts remembered by the complainant or witnesses due to the passage of time since events. This is designed to protect accused persons from being wrongly convicted and provide them with a fair trial.

In this appeal, Dawson claimed that he had suffered significant forensic disadvantage due to the delayed hearing of the case and that the trial judge, Justice Harrison, had erred in not instructing himself to take this into account.

- 3 appeals against conviction: The Crown case against Dawson was based on the lies of the accused on a number of occasions over the significant course of investigations and testimony. These appeals were based on whether Justice Harrison’s reliance on the lies of the accused was correct and whether it had therefore caused a substantial miscarriage of justice; and that the verdict of guilty was unreasonable in a judge alone case where the Crown case was entirely circumstantial.

The appeal was heard in the NSWCCA over three days by Justices Adamson, Payne and Ward and was dismissed on June 13, 2024.