Defamation

Allegations of Murder and War Crimes

The paper includes a discussion of details of findings of alleged war crimes. This content is disturbing, so teachers and students must be prepared before proceeding.

To start with, I want to make one important point that is frequently over-looked about the legal proceedings involving Ben Roberts-Smith: this was not a war crimes trial or a murder trial – at least not officially.

Allegations of murder and war crimes were at the heart of the argument.

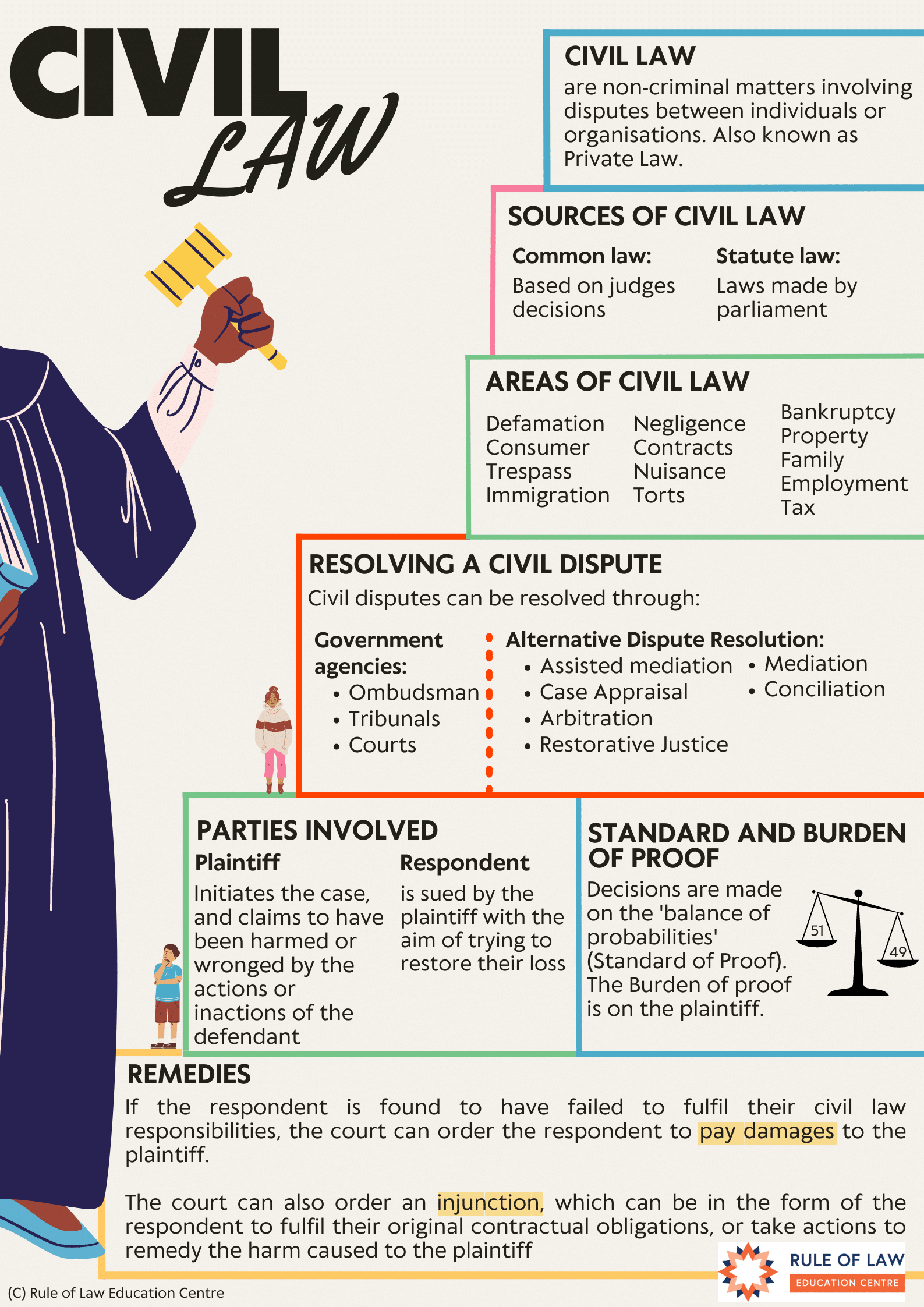

Complex Civil Dispute

But the reality is that this was merely a very expensive, very complex civil dispute in which the media successfully defended the truth of reports that this man, a recipient of the Victoria Cross, murdered people in Afghanistan.

The judge‘s decision was clear vindication for the three journalists who pursued Ben Roberts-Smith: Nick McKenzie, Chris Masters and David Wroe. But it is important to keep in mind that this affair is far from over.

The judge’s ruling is subject to appeal and media reports say Roberts-Smith – who I will refer to as BRS – is under investigation by the Office of the Special Investigator. This is the federal agency responsible for pursuing suspected war crimes and preparing briefs of evidence for the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions.

But here’s the point:

Regardless of the outcome of the appeal from the defamation case, the law will still recognise that BRS is entitled to a presumption of innocence.

That might sound incongruous or even bizarre. But it flows from one of the fundamental principles of the rule of law: that everyone is entitled to a presumption of innocence until a criminal court rules otherwise.

That has not happened. And there is no certainty it will ever happen.

The outcome of private disputes such as arguments over defamation do not negate the presumption of innocence which can be traced all the way back to Magna Carta, which was sealed in the year 1215.

This doctrine has been described as the golden thread that runs through our system of justice, and that of comparable countries such as the United States and Britain.

If there is a criminal trial…

If at some point in the future BRS is required to face a criminal court, the prosecution will bear the onus of dislodging his presumption of innocence – despite the findings in the civil case.

BRS will be entitled not just to a fair trial but to a fair trial before a tribunal that is not infected by the findings of the civil case. That, almost certainly, would rule out a jury trial.

A criminal trial would use a higher standard of proof than the standard that was applied in the defamation case.

There are also significant procedural differences in criminal justice to ensure the immense power of the state does not result in unfairness when that power is directed against individuals.

Prosecutors, for example, have a duty of fairness that requires them to disclose not just details of the prosecution case, but details that the prosecution uncovers that could benefit the accused.

The judge in the BRS case recognised these differences when he referred to arguments that his court did not have all the evidence that would ordinarily be available in a criminal trial.

That last point – about missing evidence – is troubling. It means the court made a finding of murder on the civil standard of proof without having all of the evidence that would have been available in a criminal trial.

So even if the outcome of the defamation case is upheld on appeal, any criminal prosecution would have different procedures, different rules and different evidence.

That means the prospect of a different outcome – that is, an acquittal – cannot be ruled out.

And what happens if there is an acquittal in the criminal trial?

All this puts us in a very strange position.

Journalists Nick McKenzie, Chris Masters and David Wroe have successfully defended their reports that BRS committed murder. His reputation is in tatters. But right now, he has not been charged with any office, let alone convicted.

So is it legitimate to refer to him as a murderer?

Those who choose to refer to him in that way can find support in the findings of fact in the massive judgement that was produced by the Federal Court’s Justice Anthony Besanko.

But describing BRS as a murderer, without clearly explaining the significant differences between civil and criminal justice, adds to confusion and could eventually undermine public confidence in Australian justice.

Consider the alternative: If, after the defamation case, it is legitimate to refer to BRS in an unqualified manner as a murderer, imagine the ludicrous situation that would arise if he were to be tried on criminal charges and acquitted?

He would simultaneously be a “murderer” and acquitted of murder.

What is the Difference between civil and criminal justice?

This is why it is important to be very clear about the difference between civil and criminal justice.

Soon after Justice Besanko’s decision, this point was made forcefully by Heston Russell, a retired major in the commandos who has launched defamation proceedings of his own against the ABC.

In Russell’s case, the ABC is attempting to defend a series of imputations that the Federal Court has found were conveyed in a report by journalists Mark Willacy and Joshua Robertson.

The most serious of those imputations is that Russell, when in command of a platoon in Afghanistan, was involved in the shooting and killing of an Afghan prisoner in 2012.

But let’s get back to the BRS case.

After the judgement was handed down, Russell told Sky News he was disgusted that the accusations in that case were playing out in a defamation court instead of a criminal court.

He argued that the standard of proof in the BRS case meant the media only needed to prove the truth or the substantial truth of their accusations on the balance of probabilities, which is lower than the standard used in criminal proceedings, which is beyond reasonable doubt.

But while that is true, it needs to be kept in mind that even in civil cases judges are required to adopt an approach that means the more serious the consequences of what is contested in the litigation, the more a court will have regard to the strength or weakness of the evidence.

This idea is known as the Briginshaw principle, after the name of a case in which it was applied by the High Court. It has sometimes been described incorrectly as a third standard of proof that sits somewhere between the ordinary civil standard and the more rigorous criminal standard.

It means the normal civil standard of proof continues to apply, but the seriousness of the issues at stake will affect the quality of the evidence that a court requires before coming to a conclusion.

It means that when a civil case, such as a claim for defamation, concerns the question of whether a crime has been committed, courts are also required to give weight to the presumption of innocence.

In the BRS case, the Bringshaw principle was applied and while it did not mean that a third and higher standard of proof was applied, it did mean that the judge, when he ruled against BRS, stated explicitly that he was satisfied that the proof put forward by the media was clear and cogent.

Justice Besanko made it clear he did not engage in a mere mechanical comparison of probabilities, independent of any belief in the truth of the accusations in issue.

He accepted that the Briginshaw principle meant that in matters of such gravity as accusations of murder he needed to be persuaded that what the reporters had asserted had actually taken place.

But this needs to be kept in perspective.

Even if the different standards of proof are put to one side, the judge’s finding that the murders took place was made on the available evidence – which falls short of the amount of evidence that would have been available to a criminal court.

It must therefore be less reliable than a finding by a criminal court.

The case brought by BRS did not require the reporters to defend every word of what they wrote, only the defamatory meanings – or imputations – that the judge found were present.

And even then, the main defence they used only required them to show that the imputations were substantially true, not entirely true.

They failed this test on some relatively minor matters. But the judge ruled that those accusations, which concerned a threat to a fellow soldier and an accusation of domestic violence, were covered by the defence known as contextual truth.

This meant that even though these second-order accusations could not be substantiated, they did not give rise to liability because they were less serious than the accusations that the judge found to be true.

So even though they failed to prove the truth of the second-order imputations, those accusations caused no further damage to BRS’s reputation than the imputations that were found to be true.

And those main imputations were horrific. None of them concern conduct during the heat of battle.

Here are the most serious imputations that Justice Besanko found to be substantially true:

# That BRS committed murder by kicking a handcuffed Afghan civilian, whose name was Ali Jan, off a cliff and then procuring soldiers under his command to shoot him

# That BRS committed murder by carrying a man with a prosthetic leg outside a compound and shooting him dead with a machine gun

# That BRS forced a young recruit to execute an unarmed elderly man as a form of “blooding”.

Because these findings relate to a soldier who holds Australia’s highest award for gallantry, they are a tragedy for this country. Even though they are subject to appeal they have the potential to be used maliciously by this country’s adversaries.t should be kept in mind, however, that this case also shows that in this country, unlike some others, nobody is above the law – which is another principle of the rule of law that can be traced back to Magna Carta.

The BRS case shows conclusively that the principle of equality is alive and well. Everyone is equal before the law – even a soldier who had been considered a genuine war hero.

Finding of Fact outlined in the Ruling

The events that led to the award of his Victoria Cross have now been overshadowed by the findings of fact outlined in Justice Besanko’s ruling such as the last few minutes of Ali Jan’s life.

This is what happened:

Ali Jan, who was handcuffed, was taken from a compound to a small cliff with a dry creek bed below. He was facing BRS while another soldier, identified only as Person 11, held him by the shoulder.

BRS took some steps back and then moved forward and kicked Ali Jan off the small cliff and into the dry creek bed below, injuring Ali Jan’s face and teeth.

At the direction of BRS, Ali Jan was then carried by Person 11 and another soldier identified as Person 4, from the creek bed and into a corn field on the opposite side of the creek bed.

BRS conferred briefly with Person 11 and the judge inferred that the two men agreed that Ali Jan was to be shot. Person 11 then shot Ali Jan while he was standing and handcuffed.

The handcuffs were then removed, a radio was placed on Ali Jan’s body and photographs were taken before BRS falsely reported that Ali Jan had been a spotter for insurgents and had been engaged in a shoot-out in the corn field.

For BRS, the outcome of this case has been a disaster. By initiating civil proceedings he willingly took on the risk that the accusations against him would be judged on a lower civil standard of proof instead of the higher criminal standard.

But wait there is more…

But the adverse impact on BRS is far more extensive than the destruction of his reputation. He has inadvertently helped investigators overcome some of the problems that had been hampering their efforts to prepare a criminal case against him.

His failed defamation action generated a vast amount of public evidence that will guide authorities who are investigating possible criminal charges.

Authorities are also trying to gain access to a cache of sensitive material that was used during the trial but never made public.

Late last month, the Australian Government Solicitor wrote to the parties in the defamation case informing them that the OSI – the war crimes investigator – requires access to the secret material in the Sensitive Court File that was not made public during the case.

This file contains hundreds of classified documents, the identities of all Special Air Service witnesses who gave evidence during the trial, and transcripts of all evidence given during closed-door sessions – including evidence by BRS himself.

This is likely to help ease some of the evidentiary gaps from an earlier investigation by the Australian Federal Police.

That earlier AFP investigation was abandoned because, according to media reports, it drew on evidence that had been obtained under coercion during an inquiry conducted for the Inspector General of the Australian Defence Force. For the purposes of criminal justice, evidence obtained in that manner is inadmissible for use against the person who was under coercion.

That inquiry was conducted by former judge Paul Brereton who is now head of the new National Anti-Corruption Commission.

His report concluded that there was credible information of 23 incidents in Afghanistan in which one or more non-combatants were unlawfully killed by or at the direction of members of this country’s Special Operations Task Group.

That report says this was done in circumstances which, if acceptedby a jury, would amount to the war crime of murder.

But while many people emphasise this aspect of Brereton’s report, they frequently neglect to include his caveat about the prospects of a successful criminal prosecution.

This is what Brereton said:

“In any individual case it may well be that in a forum where different standards of proof and rules of evidence apply the matter may not be proved beyond reasonable doubt.”

“The highest the inquiry’s findings rise in respect of potential criminal conduct of an individual is that there is credible information that a person has committed a certain identified war crime or disciplinary offence. This is not a finding of guilt, nor a finding (to any standard) that the crime has in fact been committed.”

Brereton’s caveats were entirely valid.

The AFP has realised that coerced testimony before his inquiry was of limited use in a court of law because of the manner in which it was obtained.

But BRS’s decision to sue for defamation has been gift for the OSI. They already have a wealth of information and are about to gain much more.

But there is still no guarantee that a criminal prosecution would succeed.

Delayed Justice: Events happened over 14 years ago

The incidents that formed the basis for Justice Besanko’s findings are now up to fourteen years old and will be much older by the time any criminal charges come to court. Memories fade with the passage of time.

The media’s successful defence in the defamation case was based, in large measure, on the oral testimony of witnesses who, in some cases gave evidence about events that took place in 2009.

The courts have long been wary about how much weight should be placed on this sort of evidence.

The late Sir Laurence Street, a former Chief Justice of NSW, expressed those suspicions cogently in a 1983 report of a commission of inquiry into events that had taken place five or six years in the past.

This is what Street wrote:

“In the intervening five or six years, rumours waxed and waned. In some cases suspicion underwent subtle change to belief, which itself progressed to reconstruction, which in turn escalated to recollection.”

In 1989 former High Court judge Michael McHugh wrote:

“The longer the period between an event and its recall, the greater the margin for error. Interference with a person’s ability to remember may also arise from talking or reading about or experiencing other events of a similar nature or from the person’s own thinking or recalling. …

“Experience . . . demonstrates only too clearly how utterly false the recollections of honest witnesses can be.”

If the material now available to the OSI results in a brief of evidence being sent to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, the prosecutors would then need to make their own independent assessment of that brief.

So if a brief were given to the DPP tomorrow, it would be startling if the prosecutors were to reach a decision within six months. If criminal charges were then laid, the preliminary jousting in court might take up to a year and that would mean a criminal trial might not start until late next year or early 2025.

At that point witnesses would be giving evidence about events that took place up to sixteen years in the past – three times longer than the delay of five or six years that so concerned Sir Laurence Street.

That sort of delay must raise a doubt about the reliability of what some witnesses might remember.

There would inevitably be arguments about whether their recollections had been influenced by subsequent events. A criminal prosecution would probably rely on many of the same witnesses who had already appeared before Paul Brereton’s inquiry and Justice Besanko’s defamation case.

Nobody knows what they were shown or told during the Brereton inquiry. But there can be little doubt that they would have been influenced by the findings of fact in Justice Besanko’s 727-page judgement. And those findings, it should be kept in mind, are not based on all the evidence.

This is copy of the paper delivered on Friday 21 Jully 2023 at a conference of the Business Educators Association of Queensland, with an extract published in the Australian Newspaper.

Further Commentary by Chris Merritt:

Special Forces Commando Heston Russell and ABC Defamation Case

July 2023

The public interest defence is a new defence for defamation law introduced in 2021 (see further details here). It has not been tested but any claims will come down to a question of reasonableness. Was it reasonable to present the material? If you look at the facts of the Russell Case, the source was not a witness to the allegation but heard something on the radio. Was this reasonable or the ABC to present this material?

Ben Roberts-Smith Defamation Case

June 2023

This decision is tragic for Australia, and it proves yet again if you are going to sue for defamation “you better line up all your ducks!”

William Duma and Australian Financial Review

February 2023

As written by Chris Merritt in the Australian (click here to read the whole article), the Australian Financial Review was ordered to pay $545,000 to the man it defamed: Papua New Guinea politician William Duma.

In the judgment, Federal Court Justice Anna Katzmann goes into excruciating detail about the journalistic methods of two AFR reporters, Angus Grigg and Jemima Whyte, who received leaked documents from confidential sources and wrote a series of articles about Duma and corruption in 2020. Grigg, the main author, contacted Duma before publication but Katzmann found Grigg’s emails had been misleading in important respects and the reporters “never invited him to respond to the allegations they intended to publish”. The judge considered it “improper, unjustifiable and lacking in bona fides” not to correct errors in the articles when they had been pointed out…

Because their articles contained “extremely serious defamatory imputations”, the judge believed they should have taken particular care to ensure the facts were fairly and accurately reported.

“The evidence disclosed they did no such thing,” the judgment says. “In several instances, and contrary to what was pleaded in the defence, the journalists testified that they did not believe that what they had written in the matters complained of was true. “In some instances, one or both of them conceded that statements they had made in the articles were not true,” the judgment says.

The media has complete control over something more decisive: its own procedures. When it comes to public interest journalism that means getting your facts right, getting the other side of the story, conducting yourself fairly and correcting errors promptly.

In the Duma case, none of those things happened at the Financial Review. That is why they lost. The newspaper did not seek to defend the truth of what it had published, choosing instead the defence of statutory qualified privilege which depended on proving that it had conducted itself reasonably.

That failed because, according to the judgement, the reporters concerned did not take proper steps to verify the accuracy of the material upon which they relied, and while they sought comment from Duma about some things they intended to publish “they initially misled him and did not fairly publish the substance of his responses”.

These failings matter because public interest journalism is vital to free societies. It is the institutional version of freedom of expression.”