The High Court is tasked with interpreting the Constitution to determine the scope of the powers of the Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. If the High Court determines that a particular statute, or part of a statute, is outside the law-making powers of Federal Parliament per s51, then the statute, or part of it, will be constitutionally invalid.

Love v Commonwealth; Thoms v Commonwealth [2020] HCA 3 (‘Love and Thoms’) was a historic High Court decision which considered the scope of the ‘aliens’ power in respect of two non-citizen Aboriginal Australians. In this case, the High Court was tasked with ascertaining whether the scope of ‘aliens’ provided by s 51(xix) included non-citizen Aboriginal Australians.

This controversial majority decision of (4:3), made up of Justices Bell, Nettle, Gordon, and Edelman found that the ‘aliens’ power did not apply to non-citizen Aboriginal Australians. This means that, regardless of whether an Aboriginal Australian is a citizen or not, they cannot be considered an ‘alien’ under s51(xix) of the Constitution because they are subject to a new category of ‘non-citizen, no-alien’.

ALIEN CITIZEN NON-CITIZEN, NON-ALIEN

Click to Jump to Section

Background

The Commonwealth Parliament can only make laws that are within the power given to them in s51 and 52 of the Constitution. Each law they make must fall under what is called a ‘head of power’, all of which are listed in the Constitution.

One head of power, under s51(xix) of the Constitution is the ‘aliens’ power, which states:

51. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to …

xix naturalisation and aliens.

This gives the Commonwealth Parliament the ‘power to determine who has and has not the legal status of alien and to specify the legal consequences of that status. It also confers power to determine the conditions upon which a person may be ‘naturalised’, that is, become a citizen’ (Myers) (Shaw v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2003) 218 CLR 28).

In 2020, the position in common law was that a person was either:

ALIEN or CITIZEN

An alien has been held to mean ‘a person born out of Australia of parents who were not Australian citizens and who has not been naturalised under Australian law or a person who has ceased to be a citizen by an act of process of denaturalisation’ (Cunliffe v The Commonwealth (1994) 124 ALR 120).

Parliament’s power to determine who is considered an ‘alien’ cannot be expanded beyond those persons who would not ordinarily be considered as ‘aliens’ (Pochi v Macphee (1982) 151 CLR 101).

Facts of the Case

1. Plaintiffs with Aboriginal heritage were non-citizens of Australia.

Mr Thoms identifies as a Gunggari person and Mr Love identifies as a descendant of the Kamilaroi group. Mr Love’s father and Mr Thoms’ mother had Aboriginal heritage and were Australian citizens. Both plaintiffs were born outside Australia – Mr Love in Papua New Guinea and Mr Thoms in New Zealand, and were citizens of those countries.

Mr Love and Mr Thoms had been living in Australia for a significant period of time as visa holders. These visas can be revoked if an individual is non-compliant with visa conditions.

It must be noted that, since Mr Love’s father and Mr Thoms’ mother were Australian citizens, each plaintiff had the pathway to become an Australian citizen under the Citizenship Act 2007 (Cth),yet they did not exercise these rights.

2. Plaintiffs committed offences and faced removal as non-citizens.

Each Plaintiff was convicted of a criminal offence and sentenced to imprisonment of 12 months or more. Under s 501(3A) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (‘the Migration Act’), the Minister for Home Affairs has the right to cancel visas of non-citizens. The plaintiffs were liable to be removed from Australia as their criminal offences were a breach of their visa conditions.

The plaintiffs contended that they fell outside s 51(xix), and therefore both the Migration Act and the Citizenship Act, because they have a special status as ‘non-citizen, non-alien’. The plaintiffs submitted that this category of person refers to someone who is a non-citizen of Australia (ie a citizen of foreign country) and an Aboriginal Australian.

ALIEN CITIZEN NON-CITIZEN, NON-ALIEN

Legal Issue

In simple terms, this case centred around whether by race, as Aboriginal Australians with their unique connection with the land, they could be considered ‘aliens’ under s 51(xix) even if they satisfied the current tests for ‘aliens’ ie were born outside of Australia and a citizen of another state (ie a non-citizen).

Decision

On 11 February 2020, the High Court handed down seven separate judgements and split 4:3. The majority held that non-citizen Aboriginal Australians ‘were not within the reach of the ‘aliens’ power’ in s51(xix) of the Constitution. Therefore, non-citizen Aboriginal Australians could not be considered aliens and, therefore, could not be removed from Australia under s198 of the Migration Act. Each Justice had different reasoning for their decision.

In attempting to decide whether Mr Love and Mr Thoms were Aboriginal Australians, the Court utilised the Tripartite Test (Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1) to determine Aboriginality. This test states that a person’s membership of an Aboriginal people of Australia depends on 3 things:

- ‘biological descent from the Indigenous people and

- on mutual recognition of a particular person’s membership by that person; and

- by the elders or other persons enjoying traditional authority among those people.’

In the case of Mr Love, when this test was applied, the majority was unable to agree as to whether Mr Love was an Aboriginal Australian. However, the same test found that Mr Thoms was an Aboriginal Australian.

Summary of Judgements

Judgements of the Majority

Justice Bell

Bell J held that ‘the power conferred by s51(xix)…does not extend to treating an Aboriginal Australian as an alien because, despite the circumstance of birth in another country, an Aboriginal Australian cannot be said to belong to another place’ [74].

Her Honour held that there would be an inconsistency between the common law’s recognition (particularly in Mabo (No 2)) of the ‘unique connection between Aboriginal Australians and their traditional lands, and a finding that an Aboriginal Australian can be described as an alien…’ [71]. In outlining the special status of Aboriginal Australians, her Honour sought to ‘recognise the cultural and spiritual dimensions of the distinctive connection between Aboriginal peoples and their traditional lands’ [73].

Justice Nettle

Nettle J held that the Crown owes Aboriginal Australians a ‘unique obligation of protection’ and Aboriginal Australians reciprocally owe ‘permanent allegiance’ to the Crown [272], [279]. As Aboriginal Australians (those satisfying the tripartite test) have a connection with the land of Australia, His Honour held such a person is not an ‘alien’ within the meaning of s51(xix) and cannot be excluded from Australia. [272].

Justice Gordon

Gordon J observed that the term ‘alien’ ‘conveys otherness, being an ‘outsider’, foreignness’ and therefore Aboriginal Australians cannot be aliens because they are ‘the original inhabitants of the country’ [296]. Her Honour held that if the Court was to hold that Aboriginal Australians fall within the scope of ‘alien’, the Court would ‘fail to recognise the first peoples of this country’ and the ‘sui generis’ (unique) position of Aboriginal Australians in Australia [333]. Gordon J therefore held since that Aboriginal Australians are ‘descendants of the first peoples of this country’ and do not belong to another nation, they cannot be considered ‘aliens’ [335].

Justice Edelman

Edelman J held that the ‘essential meaning’ of the term ‘alien’ confers on individuals as being ‘foreign…to a political community’ [392]. His Honour states that ‘The metaphysical ties between that child and the Australian polity, by birth on Australian land and parentage, are such that the child is a non-alien, whether or not they are a statutory citizen. The same must also be true of an Aboriginal child whose genealogy and identity includes a spiritual connection forged over tens of thousands of years between person and Australian land, or ‘mother nature’ [466]’

As such, his Honour held that Aboriginal Australians cannot fall within the scope of ‘aliens’ since they have a metaphysical connection with the land and were part of the political community of Australia at the time of Federation, albeit with ‘fewer rights’ [412].

Judgements of the Minority

The three Justices comprising the minority, Kiefel CJ, and Keane and Gageler JJ, all delivered separate dissenting judgements.

The minority held that the tripartite test for Aboriginality unlawfully allows elders and the Aboriginal community to determine Aboriginal status and, therefore, whether they are non-aliens. This compromises sovereignty and is beyond the constitutional capacity of an ordinary person.

Kiefel CJ held that ‘alien’ ‘describes a person’s lack of formal legal relationship with the community or body politic of the country with which they contend to have a connection’ [18]. Similarly, Keane J noted that Mabo (No 2) does not identify formal legal status ‘between an individual and a sovereign power’, but a ‘spiritual and cultural connection’ [194].

Gageler J acknowledged the common law recognition of native title but felt that a continuing connection to land should not be a means of granting automatic citizenship.

Therefore, the minority held that the Commonwealth’s constitutional power under s 51(xix) should not be limited by race. In their judgements they held that Aboriginal Australians should not operate as an exception to the classification of ‘aliens.’

Controversy

The decision in Love and Thoms created significant controversy, suggesting that the High Court had misrepresented the common law, engaged in judicial creativity, attempted to remedy historical wrongs and override the sovereignty of the Crown.

Misrepresenting the Common Law

Love and Thoms established Mabo (No. 2) as having significance beyond native title. It has been stated that this decision represents a ‘radical departure’ from precedent and the common law. In their decisions, the majority relied upon the common law in Mabo (No.2) ‘that concerned the recognition by the common law .. of certain “native title” for the purposes of land claims.

It has been questioned whether the connection to land necessary for recognition by the common law of native title should have been used in Love and Thoms. At [31], Kiefel CJ argues it is an ‘entirely different area of law’ that has nothing to do with the usual criteria for determining whether a person is an alien as a matter of ordinary usage’ (Myers).

Judicial Creativity and the role of the High Court

There has also been controversy regarding the activism of the judges and whether they abandoned orthodox methods of constitutional interpretation (Gerangelos) and usurped the role of Parliament.

One perspective is that when the High Court considers broader social factors, rather than just applying the law, it can be dangerous because it is beyond the ‘proper role of the High Court’ which is to uphold the Constitution and interpret the law (Merritt).

Judicial creativity becomes particularly dangerous when High Court decisions take into account societal values that are ‘inconsistent with mainstream community values’ (Begg) and subsequently takes upon the role that is best left to Parliament.

Gageler J in his minority decision highlighted that to create a race-based constitutional limitation was a “supra constitutional innovation” (Myers) and a possible threat to the separation of powers.

The opposing perspective was that this approach is consistent with previous decisions by the High Court and that ‘the issues .. of indigeneity at the crossroads with aliens power, was so compelling, that it had to be resolved at a Constitutional level.. they were able to do so by reference to the type of considerations that the Court has on various occasions taken into account which go beyond purely textual, contextual and conceptual approaches, indicates that they were not engaged

in “unorthodox” techniques of interpretation but were able to do so within the broad range of mainstream approaches”’ (Gerangelos).

Attempting Legal and Political Reparations

The majority decision in Love and Thoms has been viewed by some to reflect ‘legal and political efforts at trying to remedy’ the historical constitutional discrimination against Aboriginal people (Morris).

‘Nettle J’s recognition of the ‘unique obligation of protection’ owed to Aboriginal people by the Crown in right of the Commonwealth, which may represent the beginning of a shift in Australian law towards acceptance of a broader fiduciary obligation in this context…. Parliament should take the Court’s decision, a declaration of the unique constitutional position of Aboriginal people, and build upon it.’ (Wells)

Assault on Sovereignty

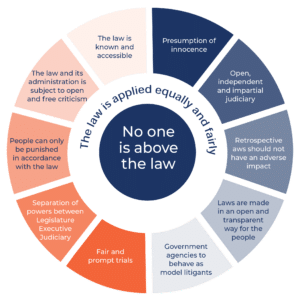

In Australia, sovereignty rests with the Crown and the Commonwealth Parliament has supreme law-making powers. This sovereignty is vital to the ‘welfare, security and integrity of the nation’ (Re MIMA Ex Parte Te (2002) 212 CLR 162) and is a critical part of the rule of law where laws are made in an open and transparent way by the people.

It has been argued that this decision seeks to give Aboriginal elders powers which ‘would supersede the sovereignty of the Crown’ (Begg) and place the elders and their law making abilities above the law. The 3-part Aboriginality test developed by Mabo (No 2), and recognised in Love and Thoms, depends upon ‘biological descent from Aboriginal people and on mutual recognition of a particular person’s membership by that person, as well as the elders or other persons enjoying traditional authority among those people’ (Begg).

Therefore, the ability of an individual to prove Indigeneity rests with the decisions of Aboriginal elders that is ‘based on an identification of race by reference to a vague criteria which are incapable of clear and objective application.’ (Myers) This is said to take away Parliament’s power, as assigned by the Constitution, and places it in the hands of a non-constitutional, non-legally-accountable group without any constitutional power.

As Keane J noted in his dissent ‘To assert that the ordinary application of laws made pursuant to s 51(xix) of the Constitution of foreign citizens born outside Australia such as the plaintiffs is displaced as a result of recognition by members of the Aboriginal group from which they claim descent, is to assert an exercise of political sovereignty by those persons’ [197].

Race Based Citizenship

The decision in Love and Thoms has led many to comment that it is inconsistent with democracy. The fact that it ‘creates another class of people’, as the Minister for Home Affairs said, (that is; the ‘non-citizen’, ‘non-alien’ category) fails to recognise the concept of equality before the law. By entrench[ing] inequality on the basis of race, many have considered that the ruling subordinates equality to the attaining social justice.

In his dissent, Gagelar J refused, as a matter of principle, the creation of a constitutional race-based distinction [133].

Arguably the most significant implication of this ruling is the notion that the ‘floodgates’ will open as every future deportee, who has committed a crime and is due to be deported, searches through their family tree to locate an Aboriginal ancestor so as to hold themselves out to be protected by the Crown and avoid deportation. This implication highlights the unequal application of the aliens power on the basis of race.

Further Reading

Begg, M. (2021). Courting Calamity. Retrieved from https://ipa.org.au/ipa-review-articles/courting-calamity

Gerangelos, P. (2021). Reflections upon constitutional interpretation and the “aliens power”: “Love v Commonwealth.” Australian Law Journal, 95(2), 109–125.

Merritt, C. (2022). High Court to Control the Indigenous Voice. Retrieved from https://ruleoflawaustralia.com.au/commentary/high-court-to-control-the-indigenous-voice/

Morris, S. (2021). Love in the High Court: Implications for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition. Federal Law Review, 2021, Vol 49(3), 410-437

Myers, A. (2023). The Thirteenth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Two Recent Constitutional Cases. Retrieved from https://www.samuelgriffith.org/2023

Wells, F. (2020). Heartbeat in the High Court: “Love v Commonwealth” (2020) 375 ALR 597. The Adelaide Law Review, 41(2), 657–670.