Human Rights Videos

Interviews with Lorraine Finlay,

Human Rights Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission

Lorraine Finlay, Human Rights Commissioner with the Australian Human Rights Commission, sat down to chat on camera with one of our Paralegals, Kate, at the Rule of Law Education Centre about human rights in Australia.

The first video provides a discussion on various aspects of the promotion, protection and enforcement of rights in an Australian context and covers not only human rights basics, but also discussions on how we prioritise rights, the introduction of an Australian Bill of Rights in the Constitution, Asylum seekers, the rule of law and the recent High Court decision in the case of NZYQ, and the role of the Australian Human Rights Commission and its relationship with the Australian Government.

Three contemporary issues videos provide an examination of Modern Slavery, the impacts of Artificial Intelligence on human rights and the right to free speech in Australia. These videos also look at how in Australia we address the tensions between conflicting rights and opinions in meeting the needs of members of the Australian community.

Video 1: Human Rights Explainer

Human Rights and Modern Slavery

Human Rights and Artificial Intelligence

Human Rights and Freedom of Speech

Further Articles by Human Rights Commissioner

Transcripts and further resources on Human Rights

Understanding Human Rights in Australia

Video 1: Human Rights Explainer

Understanding Human Rights in Australia

The video is a discussion on various aspects of the promotion, protection and enforcement of rights in an Australian context and covers not only human rights basics. It also looks at how we prioritise rights, the introduction of an Australian Bill of Rights in the Constitution, Asylum seekers, the rule of law and the recent High Court decision in the case of NZYQ, and the role of the Australian Human Rights Commission and its relationship with the Australian Government

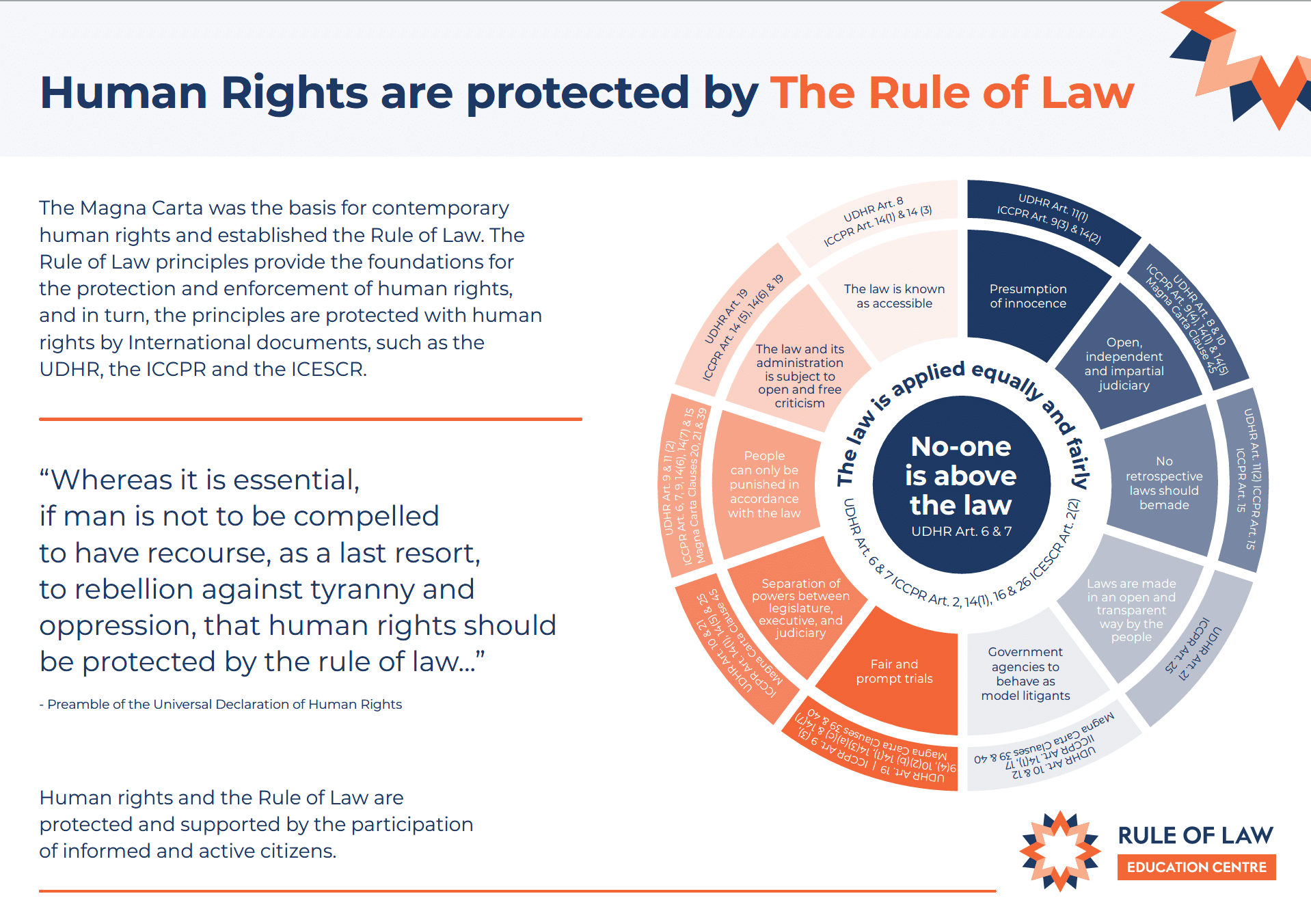

What is the relationship between human rights and the rule of law?

Human rights and the rule of law are just inextricably linked. If we look to for example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the preamble it tells us that human rights have to be protected by the rule of law, and we know that if you don’t have the rule of law – the idea that no one’s above the law and the idea that the law has to apply equally and fairly, not just to citizens but also to the government – without that, human rights can’t be properly protected, and even more importantly they can’t be properly protected for the most disadvantaged and vulnerable in our communities.

Rights in Australia are protected by a combination of the Constitution, Statute Law and Common Law. Which is the most effective way to have rights protected?

There is no one perfect way of protecting human rights and I actually think when you get down to it the most important thing isn’t the Constitution or a particular law or the common law. The most important thing is actually having citizens who believe in human rights and who are willing to see human rights enacted and part of their day-to-day lives.

I’ll give the example, if you look right around the world some of the best human rights constitutions in the world are in some of the least human rights friendly jurisdictions and it’s something that is really important for us to keep in mind, the law is an incredibly important tool it’s really important to have human rights compliant laws but in and of themselves unless you have citizens and governments that are willing to comply with the rule of law those human right protections are really not as helpful as they should be.

Should Australia have a Bill of Rights? What are the Pros and Cons?

It is a really important conversation to be having because we always need to think about how do we want to protect rights and what more can we do to better protect our human rights and so the people who argue for a Charter of Rights would point to the fact that it offers Express Clear protection. That it is a way of making human rights accessible to people it’s a way of educating people about what our rights are and it’s a way of providing clear guidelines to government – more than guidelines because they’re enforceable – but a clear outline to government of what’s expected of them and citizens with clear remedies if their rights are breached. The other side of it is that if you actually write your rights down in that way, you actually restrict them, because you’re limiting them to what’s written in the charter, and where charters really have challenges is when it comes to determining where the balance lies between conflicting rights. So, when you put a charter into place, what you’re really saying is who gets to make the final decision about conflicting rights and how we strike the right balance. In our system at the moment, that’s the Australian Parliament, with a Charter of Rights, that becomes the Australian Judiciary. So those questions are transferred from the parliament to the courts and that’s really where the debate lies. Where do you want that final decision to rest, and in my view, it is more democratic to have it resting with parliament.

What are some potential conflicting rights if Australia was to introduce a Bill of Rights?

Australia is, one of the few countries in the world that’s a western liberal democracy – in fact, the only one that doesn’t have a Bill of Rights. That doesn’t mean that the countries that do have them don’t have the same human rights challenges that we do. And I think that’s a really important point to understand. No country anywhere in the world is perfect when it comes to Human Rights, and despite the different mechanisms that different countries use, be it Constitution, statute, common law, we still all face human rights challenges and still all need to do more to make sure human rights are protected.

What are some examples of rights protected by the common law?

The common law really, from the starting point, is about protecting rights because the very first idea of the common law is that you, as an individual, are free to do anything that you want unless it’s limited expressly by law. And so the idea of the common law is, the starting point is very freedom focused, with the law then coming over top only to tell you what you can’t do and place limits around that. So the common law, from the start, is really based on the idea of freedom and rights.

It is really interesting how so many of our rights are still embedded or arrive from the common law. There’s a great example of a speech given a few years ago by Robert French, the former High Court Chief Justice, where he spoke about the common law really being the heart of Human Rights and so many of our fundamental rights and freedoms stemming from that. And increasingly we’re seeing statute law becoming more and more important, but the foundations really do lie in the common law.

Do any Government policies or laws conflict with Human Rights Acts eg in Victoria, ACT and Qld ?

Proponents of charters of Rights would tell you that the COVID example really shows how Charters can be effective because they did provide people with remedies in some cases, albeit the remedies coming a long time after the rights had been breached. But what proponents will say in Victoria, ACT, and Queensland is that those jurisdictions, all of whom have Human Rights Acts or Charters, really show how Charters have two key impacts.

The first is they give individuals direct legal remedies when their rights are breached or an opportunity to raise those issues. And the second thing is that Charters create a rights compliance culture, and particularly when you look at the dialogue models that we have in Australia. The idea being that even if an individual can’t themselves bring a legal action, hopefully, Human Rights Charters result in the public service when they’re crafting policies and crafting laws taking a more human rights-compliant approach.

What we saw in COVID is that it isn’t that straightforward, because I would say that if you look, for example, at Victoria, which has a Charter, the fact is they took the most restrictive approach of any state in Australia to the COVID-19 pandemic and restricted rights in a much tougher way and for a lot longer than other jurisdictions. So, it showed again that a charter in and of itself isn’t the single answer to any of this and that it really can’t protect rights unless you have a rights-compliant culture underneath and people wanting to see those rights.

What legal remedies are there if Australia doesn’t have a Charter of Rights?

Charters of Rights provide legal remedies – because others don’t provide a direct right to remedy. That is dependent on the type of Charter that you have. But certainly, without Charters, you still do have human rights. So, it’s not the case, for example, in the COVID-19 pandemic, that Victorian people had human rights but New South Wales people didn’t. And in actual fact, I think you can make a strong argument that rights were better protected in New South Wales without a charter because, in fact, you had a government that was focused on trying to strike a balance. And again, there’s a whole separate discussion about whether that balance was right and where rights could have been better protected during that period.

But in terms of the question of Charters or not, without Charters in Australia, we still have a constitution that doesn’t contain Express Rights – well – doesn’t contain many Express Rights or a full Bill of Rights but certainly does contain rights protective features. By that in particular, I mean when you look at the institutional framework it sets up things like the separation of powers, judicial review, federalism, responsible and representative government. There are a whole range of features in the Constitution that don’t protect or call out an individual right but provide protection for rights as a whole because of the way they limit government power and put checks and balances in place.

And then in addition to that, we’ve got a whole range of statutes that protect human rights, we’ve got the common law that protects human rights, and even down to the way that we interpret statutes using the principle of legality. There are a whole range of mechanisms that we have for protecting rights through the law. And then a whole range of mechanisms in terms of institutions like the Australian Human Rights Commission that are designed to protect and promote human rights in Australia.

What is the role of the Australian Human Rights Commission and what power do they have?

The Australian Human Rights Commission has a really important role in promoting and protecting human rights in Australia, and it does that in a number of ways.

So part of our job is education and awareness-raising in Australia, having that conversation about why human rights matter and what more we need to do. Part of it is providing recommendations and advice to government in terms of policies and laws and whether they’re compliant with rights. We hold our own inquiries and do our own research into a variety of things. So one example of that is, in my role as a Human Rights Commissioner, I engage in regular inspections of immigration detention centres to look at how they – if they – meet minimum human rights standards.

But then another thing that we do that’s really important is we have a complaints and conciliation function. So Australians have the ability under our legislation to bring certain complaints to us when their human rights are being breached. We’re not a court, we can’t make a finding determination, we can’t order remedies, but we can bring parties together to conciliate disputes and try to find a way to constructively work through those to hopefully help people realize their human rights and have them protected.

What does the Australian Human Rights Commission do to protect Human Rights?

We do a whole variety of things to promote human rights, and obviously as the Human Rights Commissioner, I have a focus on human rights generally. But in addition to myself, we have a president, and we have, in total, seven specific purpose Commissioners. So we have Commissioners who focus on particular human rights issues. For example, there’s a National Children’s Commissioner who looks particularly at children and their human rights, and we have a sex discrimination commissioner who looks particularly at ensuring gender equality within Australia. That’s just a few examples.

But what it means is that we can focus across the board on human rights, recognizing that human rights aren’t just about one group of people or one particular right, it’s about everybody in the Australian community and the full range of human rights that we want to see reflected in our country.

What is the relationship between the Australian Human Rights Commission and the Australian Government?

We are technically part of the government, but we’re independent from the government. So we’re accountable to the parliament, we report through the Attorney General’s Department to the parliament of Australia. But really importantly, our independence is protected under our statute. And what that means is we have the power to be able to be very open with government and to criticize them where that’s necessary. So we have to take a constructive role, we want to obviously work with government to make sure that human rights are protected, but where necessary, we will be critical and we are able to do that because of our independence, which is protected under law.

Does the Australian Human Rights Commission operate on an international level?

Our primary focus is human rights in Australia, but we are Australia’s national human rights institution, or NHRI as they’re called, and NHRIs exist not in every country around the world, but in a significant number of countries around the world. NHRIs, under the United Nations system, have particular roles and responsibilities that they do play, again providing an independent voice to the United Nations with respect to the country that they’re from. So we do regularly make representations to, and appear before the United Nations on a variety of issues to ensure that we provide them with up-to-date and independent information about what Australia is doing with respect to our international human rights obligations.

And again, while our focus is Australia, we work really closely with other human rights commissions and similar bodies around the world simply to recognize the fact that human rights are universal and many of the issues we’re facing are both issues that other countries have as well, so we can learn from each other, but are also issues where we need to have cooperation, because if you look at things like modern slavery, for example, no one country can deal with that problem on their own. We actually all do need to cooperate. And so we do a lot of work with our international colleagues to make sure that we are learning from each other, but we’re also cooperating to really try and maximize the impact we can have.

Are there some Human Rights that need greater protection than others?

If you go back to the foundation of human rights, the idea is they’re indivisible and they’re non-hierarchical. So no one human right is officially more important than another. We don’t rank them. But obviously, it is important to have a focus on all of them, and there are times when the direct impact of restricting a particular right will be so significant and serious that it perhaps does need to take priority over other rights where the direct impact of harm is a little bit less.

So it is a matter, when rights come into conflict with each other, of working out not which right is more important, but of how you can better balance them out to make sure you maximize rights protection across the board and minimize the harm that’s caused to people when their rights are breached.

Are there any rights that are currently being focused on by the Australian Human Rights Commission?

In terms of key human rights issues in Australia, again, there are a number of issues that have been there, unfortunately, for a really, really long time and that are significant challenges and that have been a core focus of our work at the Australian Human Rights Commission. And I guess, to look broadly at the commission as a whole, some of those key issues include things like the continued entrenched disadvantage amongst Indigenous communities in Australia, and we see that in a variety of policy areas, be it the criminal justice system, healthcare, education, housing. The list goes on.

If you look currently, the Royal Commission in relation to disability, which recently handed down findings that gave us a really clear picture of the work that Australia needs to do to meet its obligations in relation to people with disability. If we look at rates of domestic and family violence, child abuse, and neglect, there’s a whole variety of really serious issues across Australia.

But in terms of my work, I particularly focus on the work that we do to promote and protect fundamental rights and freedoms. So things like freedom of speech, freedom of movement, freedom of association. I also particularly focus on our areas of work around modern slavery, around detention practices, and in particular, torture prevention. So looking at the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture, our work around technology and human rights, business and human rights, and immigration and asylum seekers. So they’re the key areas that I focus on, but that’s more because of the way we break the work up in the commission rather than saying those areas are more important than anything else.

How is the recent High Court decision NZYQ important from a human rights and rule of law perspective?

I think that decision is really important in terms of the rule of law impacts and what it says about the government being required to comply with the law in the same way that citizens are, and that’s something we really take for granted in Australia, but it is actually a profoundly important idea that the law doesn’t just apply to each and every one of us, it also applies to the government and it limits their power and means they can’t just do whatever they want. So NZYQ, again, regardless of the fact that it’s a controversial decision and people might have different views about it, from a rule of law perspective, it’s a really important example of how those concepts apply in Australia and how even when the government might not like a decision of the Court, they do comply with it. And if you look right through the history of the High Court of Australia, even though we don’t have a Bill of Rights, human rights are an important thread in many of the cases before the court, even if not expressly from a human rights perspective, also from a constitutional perspective in terms of reinforcing those concepts around the rule of law and checks and balances on government power.

Are there any human rights that are more important for young people and what do young people need to know and do in regards to human rights?

It is really important just as a starting point for young people to have an interest in human rights and an understanding of what human rights mean to them because, again, it is something that is so easy for us to take for granted in Australia. We’re not perfect when it comes to Human Rights, but when you look comparatively around the world, we can be really proud of the country that we’ve built and the way we have got human rights at the core of that even if we don’t always meet the ideals that we set for ourselves. So I think for Australians, it’s important not to take that for granted and to understand that human rights are really important but they’re not inevitable.

So unless we’re constantly renewing and reaffirming our commitment to Human Rights, it’s so easy for them to be eroded and restricted and to fall away literally overnight. And we saw some of that happening with the Covid-19 pandemic where I think a lot of Australians were surprised at just how easily rights could be removed in Australia. And it just highlights the need for young people to actually understand what rights mean and to understand how they can impact human rights, both through their day-to-day lives. Eleanor Roosevelt famously said when the Universal Declaration was first created that human rights actually begin in small places close to home. And I think that’s really true because we often talk about government policies and big plans but actually at its heart human rights is about how we treat each other as human beings. And so for young people, I’d say the first thing is living human rights in your daily life, making sure you bring those values of kindness and respect and empathy and compassion to everything that you do in really small ways.

But the second thing is to actually be engaged as citizens in helping to build a better and fairer future. And the way to do that is by getting educated, getting informed, making sure you’re engaged and active in your community. And even simple things like not taking your right to vote for granted is really important when it comes to building the kind of society we want in the future and having human rights at the heart of that.

Video 2: Modern Slavery

Contemporary Issues in Human Rights

This video discusses what modern slavery is, how it is relevant to human rights, and whether or not modern slavery is present in Australia. Lorraine Finlay also discusses the protections and legislation surrounding modern slavery, including what can be done to improve the current protections, and make responses more effective.

What is Modern Slavery and how does it relate to human rights?

It’s an incredibly important issue, and of course, slavery is something that people often have opinions about from what they know occurred hundreds of years ago, what they’ve seen in movies of slaves being in shackles and chains. But actually, modern slavery is something that is still a continuing problem but does look a little bit different. So in Australia, we have a definition of modern slavery under section four of our Modern Slavery Act, which talks about a range of behaviours, everything from human trafficking to the worst forms of child labour.

So modern slavery is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of exploitative behaviours that really take away a person’s freedom to make their own choices and decisions. But one of the really important things to realize is that there’s no universally accepted definition of modern slavery around the world, and in fact, despite Article four of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights telling us that no one should live in slavery or servitude, we know that over half the countries around the world don’t actually at the moment have modern slavery as something that is criminalized or have laws against the enslavement of people.

Is there Modern Slavery in Australia?

The reality is modern slavery isn’t just a problem that exists in other places; it is an issue here in Australia, and the statistics are overwhelming. If you look at the most recent estimates from the Walk Free Global Slavery Index, they estimate that around the world, almost 50 million people every single day are living in conditions of modern slavery, and one in four of those victims are estimated to be children. We know that in Australia, the estimates are that 41,000 people on any given day are living in conditions of modern slavery. And that can be everything from labour exploitation to sexual trafficking, through to forced marriage. So it’s a wide variety of behaviours. But the other thing that’s really important to remember is that the statistics don’t actually tell us the full story about the human suffering and the human impact because behind every number, there’s an individual human being who has hopes and dreams for their future but who, because of the conditions they’re being kept in, are having their human rights severely curtailed, and it causes an enormous amount of damage and harm.

How does the law provide protection against Modern Slavery in Australia?

There are a variety of legislative responses. The first thing to note is that modern slavery itself is criminalized under our criminal code, and there are a variety of offenses relating to, for example, human trafficking. So there are a variety of offenses under the criminal law. But there’s also a Modern Slavery Act, which looks at making sure that businesses take action to make sure that their business activities aren’t contributing to modern slavery and they don’t have modern slavery in their supply chains. That’s a transparency model law, which means it’s about ensuring that businesses are open and accountable about the steps they’re taking to ameliorate the risk of modern slavery. One of the challenges though is that the law, in and of itself, does need strengthening. For example, there are no penalties attached for businesses not taking action to address modern slavery. So, I think that’s one of the things we could do to really help strengthen Australia’s response.

What can be done to improve the protections for Modern Slavery?

There are a whole variety of things that we could and should be doing to strengthen our response. So I think the first point to make is that Australia should be really proud of the role we’ve played in terms of taking steps to combat modern slavery. We were the second country in the world to introduce modern slavery legislation. We were the first country in the world to introduce a public online repository for modern slavery statements. And when you look around the world at the role that we’ve played, we’re taking a leading role in concrete activities to try and help identify and protect victims and ensure that perpetrators are prosecuted and punished.

But I think even though we’ve done all that, we can do more. That’s both through reforming our laws, and we’ve just had a statutory review into Australia’s Modern Slavery Act, and there were a number of really significant recommendations made about what we can do to improve that legislation. But also, things like New South Wales has an Anti-Slavery Commissioner, who was only introduced a few years ago, and that’s a role that’s making a real difference in terms of raising awareness, educating people, educating business and government about what they can do to help address modern slavery, and doing things like looking at ways government procurements can be improved to help eradicate modern slavery from the supply chain and really improve responses. So I think a federal Anti-Slavery Commissioner would be something that would be really helpful, and the national parliament’s currently considering legislation to introduce a national Anti-Slavery Commissioner.

How can current responses to Modern Slavery be more effective?

A really important part of that is ensuring that the laws around modern slavery are as strong as they possibly can be. But it’s also really important to make sure that government, businesses, and individuals actually understand what modern slavery is and what things they can do to help address it. So if we look at individuals, you know, obviously each of us as individuals are not going to be able to solve modern slavery on our own overnight. But there are things we can do, like making ethical purchasing decisions, for example, to think about the way our behaviour could actually make a difference. I think it’s something that’s really important for all of us to realize: firstly, that modern slavery does occur in Australia, and secondly, there are steps that we can take as consumers to actually think about helping to be part of the solution.

What is the Chocolate Scorecard?

So just last week, I went to the launch of the Chocolate Scorecard, which is an amazing initiative done by Be Slavery Free. What they do is they go and assess and work with chocolate companies, retailers, suppliers, and actually rank them or give them scores in terms of, for example, are they addressing slavery risks? Are they paying living wages to the people who are producing the chocolates? How ethical and environmentally conscious are they in terms of the way they produce chocolate, the way they sell chocolate? What it does is it gives you an easy way as a consumer of identifying the companies that are doing a really good job to not just produce really yummy chocolate but to produce it in a way that’s ethical, and that when you purchase that as a consumer, actually does make a difference.

How can we help with Modern Slavery?

That’s a really important thing to realize about human rights. You know, it can be really overwhelming, particularly at the moment with everything that’s going on in the world. It’s so easy to see all of the things that are going wrong and all of the challenges we face, and they’re really important to recognize, be honest about, and to be concerned about. But we have to be really positive about the fact that we can make a difference as individuals. This isn’t something that we should just despair about; it’s actually something where we should get involved, think about in our own lives what little things can we do that might not solve all of the problems overnight but will actually make a difference because individuals can actually have a real impact. And ultimately, human rights, you know, the big declarations, the big principles, they’re important. But human rights, at its heart, is about how we treat each other as human beings, and so, in our day-to-day lives, living those values and making sure that we bring human rights to life through the decisions we make and the things we do, that’s really important.

What does the Australian Human Rights Commissioner do in response to Modern Slavery?

So we do a number of things, and if we look particularly at the modern slavery issue, one of the things that we do is we are part of government reviews and government inquiries to actually look at how our laws could be strengthened in Australia. So we play an important role in terms of consulting on those things. We’re part of a number of formal groups that look to address modern slavery. So, for example, there’s the National Roundtable on Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery that brings experts together from government, academia, business, and civil society, and we sit on that to look at new approaches to addressing modern slavery. But another really important part of our role is taking a practical approach to helping create awareness and education so that people understand what this issue is but also what steps they can take to address it. So one of the things we’re really proud of is the work we do with businesses, for example, to look at what more can businesses do to help address modern slavery and how can we provide some really practical guidance and suggestions to them to help ensure that they’re able to take a really human rights compliant approach.

What effect has developing technologies impacted on Modern Slavery?

What we have seen is there are some technological developments and advancements and innovations that are really helpful when it comes to combating human trafficking and modern slavery, and there are some businesses that are producing amazing innovations that use technology in ways to help identify vulnerabilities in supply chains, to help identify vulnerabilities in communities, and to help think about ways that we can better collect data to help us address challenges of modern slavery. So technology can play a really important role.

The flip side of that is the people who are trafficking humans, the people who are criminals in this process and are doing the wrong thing, are also using technology. But they’re using it to subvert the law and to actually improve the way that they’re going about human trafficking and modern slavery. So we need to be really aware with technology that there are some enormous benefits that it can bring; it can be used in ways that really strengthen human rights.

But there are also risks; it can be used by bad people to do bad things, and we need to find ways to guard against that. So, for example, one of the emerging issues in our region is the increasing use of scam centres in Southeast Asia and people being trapped in modern slavery, forced to work in those centres to then scam people in countries like Australia out of their money. This newly emerging technology has allowed that to occur, and it’s having a really serious impact, and we’re seeing that as a growing example of modern slavery in our region.

Video 3: Artificial Intelligence

Contemporary Issues in Human Rights

Lorraine Finlay, Australian Human Rights Commissioner looks at the Contemporary Human Rights Issues in relation to Artificial Intelligence (AI). Particularly, she discusses what areas of Human Rights are challenged by developing AI technology and are there further Human Rights challenges likely to arise with the development of AI? Also, what challenges do lawmakers face in keeping up with developing technology and are there ways for AI and developing technologies to be used to protect and promote human rights?

What areas of Human Rights are challenged by developing A1 technology?

I am really excited and optimistic about AI, and that’s important to understand because there’s a lot of fear and uncertainty that surrounds it. But overall, I’m really optimistic. I think this technology is something that has so much potential. It can enhance human rights in a huge variety of ways. But we need to be really aware of the risks, and we need really early on to think through what are the human impacts of AI and the way that we use it, and how do we put the appropriate guardrails in place so that we can actually stop some of the harms that we know are starting to occur from happening.

So, some of the things that we’re really concerned about are, for example, impacts on privacy because we know that as AI takes data from people, it can draw from discrete data points a whole variety of really quite intrusive conclusions about who you are, what you do, what you like, and that information a lot of people don’t understand who holds their data, what protections are in place, and how it can be abused. So, privacy issues are really important.

I think there are a number of issues also around algorithmic bias when it comes to AI and ensuring that you don’t have discrimination actually being embedded in artificial intelligence technology, and so, examples of that are when AI is used for recruitment, for example. If the data that it’s trained on has only been given traditional CVs to learn from, in terms of, let’s say, and I’m picking a hypothetical example, let’s say an engineering company wants to use AI to help with its hiring processes. If it’s only ever hired males before because traditionally that’s been an area of high male employment, the AI training tool will learn to identify engineers as being male. And so, when that tool is then used in the engineering firm, it will recommend males. The discrimination actually gets embedded into the data or into the AI. And so, what AI can do is, rather than being a fair and more objective way of actually approaching something, it can actually embed discriminatory practices. So, we need to guard against that.

But the third thing that I think is most important is AI is starting to change our perceptions of what’s true and what’s not. This is a really big issue that we need to grapple with because we all know that there is so much misinformation and disinformation out there, and AI really challenges some of our perspectives in terms of not being sure now whether, you know, the photo that you see of Princess Kate is a real photo or isn’t a real photo. And there are some really, you know, innocuous examples of this. One of the big ones was the photo of the Pope in a big white puffer jacket, which didn’t do any harm to anybody, was a bit of a pop culture example. But there are also examples of AI, for example, being used to generate videos from political leaders making statements that they’ve never actually made. That can be really dangerous for democracy because you can then get things being said that influence the way people vote, the way people think about an issue, the way people perceive the world, and yet those things aren’t actually real. So, that idea of needing to think through truth and fiction, what’s real, what’s not, is a really challenging human rights issue.

Are vulnerable people more impacted by the potential impacts of AI?

I think one of the realities when we are talking about human rights issues is that people who are already vulnerable or disadvantaged are often the most impacted when these types of things emerge, and we saw, and it’s not an AI issue but it’s related to it with the robo-debt scandal that only happened recently in Australia. It was people who were already disadvantaged in our community who were the most affected. In terms of AI, I think that is absolutely a risk.

But the second aspect of that that we also need to think about is that growing digital divide in Australia and the risk that in our pursuit of technological innovation, we actually leave parts of the community behind. And it’s really important, for example, in terms of young people, to make sure that all young people have the opportunity to actually understand or have access to the technology that’s becoming such a part of our day-to-day lives, but have the same opportunities to understand through their schools and education how to use that responsibly and we’re not creating a real divide between students who do have access to that and students who don’t.

Are there further Human Rights challenges likely to arise with the development of AI?

I think one of the really interesting things is that, again, we tend to talk about technology in terms of individual forms of technology, so AI is separate from other things, but they all actually come together. So, if we look at AI and facial recognition technology, for example, it’s a really good illustration of the duality of this. That technology can have such benefits in terms of strengthening human rights, but it can also lead to huge problems.

In India, for example, the Delhi police used facial recognition technology combined with AI software to actually connect or run missing children through a data base, and they connected over 3000 missing children with their families in a matter of a weekend. That is enormously powerful. That’s an amazing result. But that same technology was also used to profile individuals who were protesting against the government, and in that way, it was used to shrink civil space and actually target people who were seen as holding the wrong opinions. So, that’s a really damaging human rights story. Again, it shows technology can be used for good, but it can also be used to undermine human rights. We’ve got to be aware of both of those possibilities and make sure we put frameworks in place to harness the benefits but guard against some of those risks.

What is LAWS (Lethal Autonomous Weapons)?

LAWS stands for Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, and it’s effectively the idea of like drones, but drones that are able to have a lethal impact. So, the artificial intelligence, the technology, actually makes the decision about whether the target is terminated or not. It’s the stuff of science fiction, and yet we know that these weapons are being developed. We know that these weapons are already being used, and there are examples recently in Russia & Ukraine, for example, of developments in this area that are really concerning because from my perspective, I think that ultimate decision about human life, about whether somebody is killed or not, you can’t leave that decision to a machine. That’s a decision that is always going to be difficult but has to be left to a human being, and when we look at, for example, international humanitarian law, I have real concerns about whether Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems or LAWS could ever meet the criteria that we’ve set around international humanitarian law, and without getting into the really technical details, the primary concerns are around necessity and proportionality.

So, I don’t think there’s a way at the moment for this technology to make the necessary distinctions between, for example, is somebody an active participant in war or are they an injured combatant who, under international law, can’t be attacked? Have they surrendered? Are they a civilian? Are they a combatant who’s disguised as a civilian? There are so many complexities around these decisions, their judgments that in a conflict zone need to be made instantaneously, and yet, ultimately, they’re very human decisions that I don’t want to see a machine making because the risks of that are literally life and death.

What challenges do lawmakers face in keeping up with developing technology?

One of the real challenges is the technology is always years ahead of the law. One of the things we should have learned from the explosion of social media over the last decade is that we’re really playing catch-up, and we’re looking now at putting regulations in place around social media that are needing to be retrofitted. If they’d been put into place 10, 15 years ago, some of those harms that have since occurred would have been avoided. So, that’s the approach we need to take with technology now.

We need to look ahead at what are the impacts likely to be, and how can we actually put things in place now to stop the worst of those harms from occurring? It’s a hard thing to do, but it also highlights again the fact that the law’s a really important part of this, but it’s not the only answer because if we wait for laws on everything, the technology will have already moved on. So, we need to be looking at how can we encourage people to be responsible in their use of technology, but also how can we encourage technology companies to ensure that they are ethical and responsible in the way they develop and use this technology, and that’s a really important thing.

Are there ways for AI and developing technologies to be used to protect and promote human rights?

There are a whole variety of things you can look to in terms of positive uses of technology, whether it be accessibility. I’ll give one example. We just released last week a paper on neurotechnology, which is the idea of technology that impacts on your brain. There are some really interesting trials happening at the moment about human implantations where devices are being implanted into human brains with the idea of then being able to provide, for example, people who have a disability who perhaps are paraplegic or quadriplegic to actually control a computer or control other devices using their mind. The possibilities in terms of treating Parkinson’s disease, treating epilepsy, really providing assistance from a healthcare perspective are enormous. The risks in terms of invasions of privacy, in terms of freedom of speech, in terms of the commercialization of your personal data, those risks are also really significant.

And if I give one example to highlight it, there are wearable headbands that you can now get that you attach over your head and wear, and that can actually measure your brain activity, and these are being trialed by some mining companies for use by their truck drivers because what it allows you to do is identify when the truck driver is falling into a micro sleep. So, from a work health and safety perspective, enormously helpful in terms of ensuring that workers aren’t overly fatigued and they can take breaks whenever they’re becoming unsafe. The same technology has also been trialled in China on school children, and it’s been used in classrooms where children have been required to wear their headbands throughout their days’ lessons, and it measures whether they’re being attentive in class. And that data is sent to the teacher, to their parents, and to the school district. Now, the concern there is about the privacy of children and what happens to that data, and what does it show in terms of their attentiveness? What sort of pressure does it put them under? What does it mean for students, for example, who are neurodiverse, who might not conform to those normal or what’s considered to be a normal parameter in terms of brain activity, and who suddenly will find themselves more isolated in the classroom than perhaps they already are?

Video 4: Freedom of Speech

Contemporary Issues in Human Rights

Lorraine Finlay, Australian Human Rights Commissioner looks at the Contemporary Human Rights Issues in relation to Freedom of Speech. What is Freedom of Speech and how has it developed as a right? How is Freedom of Speech balanced with violations of other human rights such as discrimination or harassment? What are some restrictions of Freedom of Speech? Lorraine also provides an example using s18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and how this impacts freedom of speech.

What is Freedom of Speech and how has it developed as a right?

Freedom of speech is what I’d call a foundational human right in that without freedom of speech, without freedom of thought, you actually can’t exercise your other human rights, so it’s absolutely essential. And freedom of speech, of course, doesn’t start with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Our human rights started well before then, but the Universal Declaration sets out freedom of expression, and importantly, it’s not just freedom of speech, but the freedom of receiving and imparting information, freedom of conscience, freedom of belief, as well as freedom of expression. So there’s a whole variety of things that are encompassed within that.

It is recognized, and it’s an important thing to recognize, that freedom of speech is a powerful human right, but it is also a right that can be restricted. And the way that human rights law describes that is freedom of speech carries special responsibilities to ensure that you’re using that freedom in ways that don’t unduly restrict other human rights. So freedom of speech is absolutely fundamentally important, but it is a right that can be limited and restricted. The really significant question that we all need to think about is what restrictions are we willing to accept in terms of freedom of speech and where do those lines get drawn? Because that’s something that reasonable people can disagree on.

How is Freedom of Speech balanced with violations of other human rights such as discrimination or harassment?

You know, it’s really hard to say there is an absolute set line and it’s really clear and objective because, again, people have different opinions about it. My personal view is that we need to give the widest possible scope for freedom of speech, and it should be in only rare cases that we draw the line and say we actually will not allow this form of speech. To my mind, that line should be drawn at the point of incitement to violence. So the minute your speech is going to produce an action that will cause harm, that’s somewhere where the line should absolutely be drawn.

Having said that, it’s really important to say that the law is one response to these types of things. And by saying that the legal line should be drawn at incitement, you’re not saying that all other forms of speech are acceptable or are – or should be encouraged. So, for example, when we talk about taking offense and if I say something that’s really offensive to you, I don’t think the law should stop me from doing that. I think it should be allowed in a free society. But I absolutely think you should be able to call me out on that, and the community should be able to criticize what I say. So freedom of speech doesn’t mean freedom from accountability or responsibility, but the question we have to ask is when do we want the law to get involved and when do we actually want to stop speech, as opposed to simply saying we should be able to have robust discussions.

I think the final point that’s really important to make is, look, everybody says they believe in freedom of speech. It’s a really easy right to say you believe in. But if freedom of speech only means the freedom to say nice things about issues that everybody agrees on, then it’s really a freedom that’s meaningless. Freedom of speech is at its most important when it means you’re standing up for the right of people to say things that you might vehemently disagree with, but you recognize that in a democratic society, it’s absolutely critical that we have diversity of thought, diversity of perspectives, and that we’re able to actually engage with different ideas, because if we can’t do that, we really lose an important part of who we are as a nation and a community.

What are some restrictions of Freedom of Speech? What is section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act?

Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act is a provision that effectively, and I’m paraphrasing here, but effectively makes it unlawful to say something that offends, insults, humiliates, or intimidates somebody else in a public place in relation to their racial or ethnic background, and that is definitely a paraphrasing of it. The really critical thing to understand with 18C is, again, it covers a wide range of behaviours.

So at one end, there is the incitement to violence, effectively, where there are very few people who would say that that’s an exercise of free speech. But at the other end, there is the question of offensive language. And again, there aren’t many people who’d say we want people to be offensive, we want people to say terrible things to each other. The question is, do you think that behaviour should be unlawful? And that’s a really important question, because if we start making that type of speech unlawful, my concern in relation to racism, for example, is if you start outlawing offensive speech, what you’re actually doing is you’re masking the symptom, but you’re not actually dealing with the cause. Ultimately, when it comes to something like racism, you actually need to change hearts and minds, you actually need to address the cause of the behaviour. And by simply banning speech, you’re not really addressing the issue, you’re just masking the symptom.

Examples that elaborate on why Freedom of Speech is a fundamental human right?

Any student on a university campus at the moment knows why freedom of speech is so important, because if you can’t ask questions, if you can’t say what you’re thinking, if you can’t explore ideas, how can you ever learn? How can you ever develop? How can you ever understand or grow your opinions?

So, freedom of speech is essential not just in terms of being able to hear things that you agree with, but it’s actually even more important when it comes to hearing things that you disagree with, and even to the point of hearing things that you find offensive and insulting, I don’t want people to be offended, I don’t want people to feel insulted, and it is really important to make sure that we’re not discriminating against people, but what we really need to start thinking about is how we can respectfully engage in conversations that can be difficult, and accept the fact that democracy is robust, and democracy is about exchanging and challenging ideas, accepting different opinions, and one of the concerns I do have on university campuses, particularly at the moment is that students don’t feel free to be able to do that, they don’t feel free to be able to express their opinions. They don’t feel free to be able to explore different views, and its incredibly important that in the very places that are meant to be centres of learning, we actually allow that robust exchange of ideas.

I think another really important point there is, we often think in terms of human rights that there’s only ever one answer, and in actual fact, we should have robust discussions around human rights, and particularly how do we balance out competing rights, and they’re things that, unfortunately, we don’t seem to really want to discuss in an open way. There’s often a lot of fear around giving different opinions or having a different view. We do need to be free to discuss these ideas because they’re so critical to not only our country at the moment but the pathway heading on into the future. And if we want to build a stronger, fairer, better society, you can only do that by having that open exchange of ideas and the freedom to discuss different views and different values.

We really do need to emphasize the fact that human rights are often expressed through law, but they’re not a gift of the law, because if human rights are only found in laws that are written by government, if they’re the gift of government, then government can take them away. And my view, and it’s set out in the Universal Declaration, is human rights are inherent in us. They’re certainly expressed through legislation, but that’s not actually where they ultimately reside. And it’s really important that we all think about what our human rights are, why they matter to us, and what we can do to help strengthen human rights in Australia without just leaving that to be entirely the responsibility of government.

Further Articles by Australian Human Rights Commission

Further Resources by Rule of Law Education Centre

Posters

Resources

- COMING SOON Human Rights Act in Australia?: Both Sides of the Arguement

- Juggling Competing Needs in Justice System

- The Legacy of the Magna Carta on Human Rights

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights