Human Rights Treaties and International Law in Australia

Treaties created by the United Nations and other such bodies form the basis of international law and are how human rights are recognised, promoted and enforced regionally and globally. This explainer describes the ways sovereign states recognise and comply with international laws in their legal systems depending on whether they are monist or dualist in their approach. It then describes how a treaty created under international law becomes part of Australian domestic law through the ratification and accession process. An example of human rights being incorporated into Australian domestic law via the Racial Discrimination Act is given, as is the case study of Billy & Ors v Australia demonstrating what happens when Australia breaches its human rights obligations.

What is a sovereign state?

A sovereign state is a state that has the following characteristics:

- one centralised government

- has sovereignty over a specific geographic area – defined territory

- has a permanent population

- capacity to enter into diplomatic relations with other states

“State sovereignty is the ability of a nation state to make laws for its citizens without external interference. The impact that state sovereignty has on human rights influences whether there is recognition, protection or enforcement of such rights.” NSW Board of Studies

“Ratification of international treaties does not involve a handing over of sovereignty to an international body… In the absence of legislation, treaties cannot impose obligations on individuals nor create rights in domestic law.” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)

Click here for a discussion on the issues surrounding the sovereignty of Aboriginal peoples.

What is a treaty?

According to the DFAT, a treaty is “an international agreement concluded in written form between two or more States (or international organisations) and is governed by international law. A treaty gives rise to international legal rights and obligations.”

Section 61 of the Australian Constitution allows Australia to enter into treaties as an exercise of Executive Power. Treaties are then tabled in both Houses of Parliament. A treaty is generally tabled after it has been signed for Australia, but before any action is taken which would bind Australia under international law. (DFAT)

Types of treaties

Treaties are generally an undertaking by nation states to commit to certain conditions or undertakings or refrain from certain actions. They can be:

- Unilateral: Whereby a single nation state makes a declaration or undertaking that that is designed to impact only on themselves, for example, Japan’s 1998 and 1999 decision to undertake a scientific fishing program when Australia and New Zealand declined to enter into an agreement about the program. Unilateral agreements are not agreed to by other nations.

- Bilateral: Also called a bipartite agreements, whereby two nations enter into an agreement that has negotiated terms. They are written agreements signed by both sovereign states agreeing to the terms. Australia has entered into a number of bilateral agreements with other sovereign states on a range of matters, for example, extradition agreements for mutual assistance in criminal matters with a number of nation states, including the USA, France, Belgium and India.

- Multilateral: where two or more sovereign states enter into an undertaking with other nations to abide by terms set in the treaty, for example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) with 174 signatories.

However, the nature of the legal system, that is how international law is recognised by a sovereign state, determines how obligated a nation is to the terms of the treaty.

Monist and Dualist systems

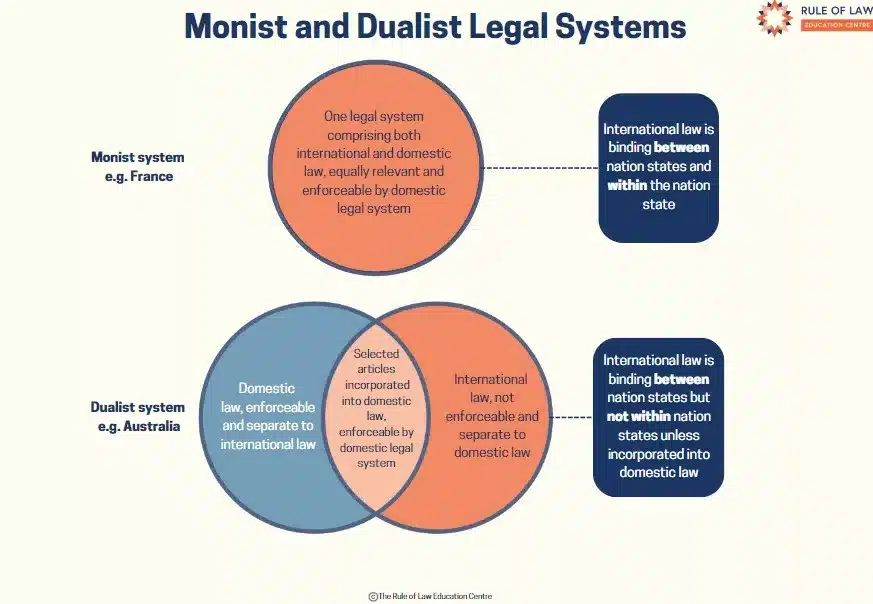

In terms of international law, nation states are able to choose how the international treaties they become party to are incorporated into their domestic legal system and operate under either a monist or dualist system.

Monist nation states, such as France, make international law part of their domestic legal framework as soon as they become signatory to a treaty or convention. There is no need for any additional law making to be completed by the governments of monist nation states for international laws to be enforceable. This approach views the international and domestic legal systems as one (mono) system as a whole that the state is bound to administer.

In contrast, under dualist systems, as used in Australia, international law and domestic law operate in tandem but remain two separate (dual), independent systems that function alongside each other. International treaties and their articles do not have an effect on a dualist state’s domestic legal system unless articles contained in international laws are incorporated into domestic laws via law making or reform processes carried out by a parliament or other relevant systems, depending on the country.

Some states can also have a mixed monist – dualist approach, such as the United States of America. In this case, international law can be applied directly in some cases, but not others. This is caused by the wording of the Constitution of that state.

Click here to download the pdf of the Monist and Dualist Legal Systems

What makes Australia a dualist nation?

The separation of powers under the Constitution makes Australia a dualist nation state. When states agree to be bound by the articles of a treaty at international law, it is the Government of the time (the Executive) making the agreement on behalf of the nation and its people. However, under section 51 (xxix) of the Australian Constitution, the power to make laws regarding external affairs is given expressly to the Parliament.

Therefore, because international laws have been created by international bodies and not the elected members of Federal Parliament who represent the interests and needs of the Australian people, these laws can not automatically apply in Australia. As with all laws created for the Australian people, any articles from international law that the Executive or people wish to see enacted have to be created through the law making or reform processes in parliament at federal and/ or state levels.

The treaty process in Australia

The legal process for Australia to implement an international agreement/treaty is the following:

Step 1: Signature – Australia as a sovereign state agrees in principle to the articles/ terms of the treaty, but is not legally bound by these.

Step 2: Ratification – is a binding agreement that Australia will implement the treaty. In the case of a multi-lateral United Nations agreements, an instrument of ratification is prepared by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and is then deposited with the UN Secretary-General after being approved by the Governor-General in Council.

Step 3: Implementation – the Parliament implements either some or all articles of the agreement as an Act of Parliament, for example, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) implements the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

Mandate to enter a treaty, ministerial and executive approval and review by Parliament are not legal steps but are steps that have been implemented as a check on the decision making power of the Executive in the treaty process.

Click here to download the treaty process PDF

Step 1: Signature

Australia signs the treaties it agrees to as part of its membership of the United Nations. In becoming a signatory to an agreement, Australia is enabled to move forward to make the articles or terms of an international agreement binding.

“… it is a means of authentication and expresses the willingness of the signatory state to continue the treaty-making process. The signature qualifies the signatory state to proceed to ratification, acceptance or approval. It also creates an obligation to refrain, in good faith, from acts that would defeat the object and the purpose of the treaty.” United Nations Library

Although not required by the Constitution, all signed treaties (unless urgent or considered to be classified in nature) are tabled in both Houses of Parliament for a minimum of 15 sitting days before any binding actions are taken so that Parliament can act as a check on the power of the Executive. This process includes the provision of reasons as to why Australia should be bound by the articles and a discussion as to key considerations (such as costs, environmental or social implications, how domestic implementation could happen, obligations under the treaty etc.)

The Joint Standing Committee on Treaties considers international treaties.

Step 2: Ratification

There are two requirements for Australia to ratify a treaty:

- Firstly, the domestic procedures required for Australia to bind itself to that treaty are completed. For Australia, this is where the decision by the Governor-General in Council to approve the treaty has been made following the tabling of the treaty to Parliament.

- Secondly, Australia declares its consent to be bound by the treaty. This requires that Australia deposit an ‘instrument of ratification’ with the United Nations Secretary General, which is a document that has been drafted by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade that expresses Australia’s acceptance of the terms of the treaty, including any qualifications or reservations.

Once ratification has occurred, Australia is bound by the treaty and is compelled under international law to proceed to incorporate articles of a treaty into domestic legislation to make them enforceable under domestic law.

“Ratification … is a voluntary undertaking by the State to be bound by the terms of the treaty under international law… If a State chooses to ratify and ‘become party’ to a human rights treaty, that country is obliged to ensure that its domestic legislation complies with the treaty’s provisions.” The Australian Human Rights Commission

“Through ratification of international human rights treaties, Governments undertake to put into place domestic measures and legislation compatible with their treaty obligations and duties.” The United Nations

Reservations

Under Article 2 (1)(d) of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), a reservation is defined as “a unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a State, when signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or to modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State.” This means that nation states can be selective about which articles of a treaty they choose to be bound by.

“A reservation enables a state to accept a multilateral treaty as a whole by giving it the possibility not to apply certain provisions with which it does not want to comply.” United Nation Treaty Collection

“Reservations and Understandings are statements made by State Parties at the end of a Convention, which limit some of their obligations under the terms of the Convention. The Australian Government has made reservations to specific Articles in Conventions where the requirement of the Article conflicts with an area of domestic law.” The Australian Human Rights Commission

Step 3: Implementation

After a treaty is signed and ratified, for any articles in the treaty to be enforceable in Australia, they must be incorporated into domestic legislation through law making or law reform processes carried out by Parliament. This is because the power to make laws is expressly conferred to Parliament under sections 51 and 52 of the Constitution.

“Implementation at the national level is the most effective way of enforcing international human rights treaties. A state needs to give effect to the treaty in its domestic law so that individuals – the primary beneficiaries of international human rights treaties – are able to enforce their rights at home.” Natalie Baird

Accession

In some cases, states may choose not to enter into a treaty at the time the treaty is negotiated and signed by other nations. This could be for reasons of conflict with another nation(s) or conflict between the terms or articles of the treaty with prevailing cultural norms or political perspectives or priorities in the state at the time. The decision of a sovereign state to not sign does not need to be permanent. Accession enables a state to enter into the treaty at a later point in time.

“Accession” is the act whereby a state accepts the offer or the opportunity to become a party to a treaty already negotiated and signed by other states. It has the same legal effect as ratification. Accession usually occurs after the treaty has entered into force.” The United Nations Treaty Collection (UNTC)

What Human Rights Treaties has Australia signed?

The Commonwealth Attorney General’s Department identifies Australia as being a signatory, or party, to the following international human rights treaties:

- the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

- the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

- the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

- the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)

- the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

- the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

There are also a number of ‘optional protocols’ that Australia is party to. These are treaties in their own right and follow the same process for implementation in Australia as other treaties do.

Example: Incorporation of Human Rights Treaties into Domestic Law

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

Signed by Australia in 1966 and ratified in 1975, the CERD is a UN convention that aims to promote ideas of racial equality while providing a legal framework for how to deal with issues of racial discrimination using legal processes. The CERD formed the basis of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (the RDA) and is one of the primary ways that Australia demonstrates that it is complying with the articles of the CERD.

The Australian Government is required to report on its implementation of the CERD every three years to the UN Human Rights Committee about its efforts to comply with the CERD and combat racial discrimination.

The RDA deals with specific matters relating to racial discrimination. Importantly, s18C of the RDA makes it unlawful to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person because of their race, colour or national or ethnic origin, promoting social cohesion and equality in Australia.

Section 10(1) of the RDA states that all people are entitled to equality before the law regardless of their race, colour or national or ethnic origin. If a law removes a right or limits the extent of it for a particular race, s10 can be invoked to strike down that law as being racially discriminatory.

Section 8 of the RDA references the CERD and provides exceptions to s10. These exceptions are called “special measures” and are actions that may be discriminatory but are taken to assist a specific racial or ethnic group to secure them full and equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Case Study: What happens when Australia breaches its obligations under international law?

Billy and Ors v Australia [2022] UNHRC

The landmark case of Billy and Ors v Australia was heard and decided by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). It was the first time a UN body had found that inadequate climate policy was a breach of human rights, and highlighted the disproportionate effect of climate change on Indigenous Peoples’ homes and culture.

Daniel Billy and Ors are Torres Strait Islanders who took action against the Australian Government (the State party) in 2019 through the UNHRC for inaction on climate change. They believed that this inaction had failed to protect the people of the Torres Strait Islands from the adverse impacts of climate change, which had led to the following human rights breaches protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

- Article 2 (2) – Where not already protected in existing legislation or other measures, the state takes necessary steps to adopt laws to give effect to the rights in the Covenant: the state failed to adopt such measures to protect the rights of the complainants contained in the ICCPR

- Article 6 (1) – The right to life: the state party had failed to respect the right to a healthy environment, which is included as part of the right to life

- Article 27 – Right to enjoy and engage in own culture and language: climate change comprises the traditional way of life of the complainants and threatens to displace them causing irreparable harm to their ability to enjoy their culture

- Article 17 – Right to freedom from unlawful interference with reputation, privacy, family, home and correspondence: climate change interferes with the privacy, family and home of the complainants as they may be forced to abandon their homes within their lifetime. The State party (Australia) had failed to prevent serious interference with the privacy, family and homes of people in their jurisdiction

- Article 24 (1) – Right of children to have measures of protection as are required by their status as a minor, on the part of his family, society and the State – the State party had failed to take measures to protect the rights of the children of the Torres Strait Islands (some of whom were named in the action) to a healthy environment that sustains their culture and survival

In 2022, the UNHRC found in favour of the applicants under Articles 17 (right to family life) and 27 (cultural rights of the Islanders). This decision was a significant finding for all governments, putting them on notice that states have obligations to their present and future citizens to prevent climate change and its impacts on the human rights associated with a healthy environment.

Intergenerational equity and the promotion and protection of socioeconomic rights are needed to support the rule of law principles. Consideration of rights and issues such as these in government decision making promotes confidence in systems of governance and therefore supports the achievement of human rights, acts to increase democratic engagement and keeps the rule of law safe.