The Australian Newspaper: William Wentworth and Robert Wardell

Celebrating 200 years of press freedom in Australia

Introduction

The original Australian Newspaper was started in the penal colony of NSW on 14 October 1824 by William Wentworth and Robert Wardell.

The opening editorial proclaimed

“In a Colony whose energies are thus expanding, little doubt can be entertained of the utility and efficacy of an Independent Newspaper. The aggrandizement and the increasing wealth of a people introduce a complexity in their affairs; conflicting opinions and conflicting interests arise, individual influence is apt to luxuriate and flourish where there exists no corrective to check its exuberance or prevent its growth. A free press is the most legitimate, and at the same time, the most powerful weapon that can be employed to annihilate such influence, frustrate the designs of tyranny, and restrain the arm of oppression. Without its active and liberal co-operation the biased views of a party frequently preponderate, while the true interests of the public languish and are over-looked.”

What was the colony of NSW like in 1824?

The Australian newspaper was launched in ‘extremely propitious’ circumstances.

The first formal census in 1828 shows a population of around thirty thousand, 75% of which had been or still were convicts.

Economic history records reveal a flourishing economy, dependent on mining and agriculture, which surprisingly gave residents at that time one of the highest GDP’s in the world.

Yet in this growing settlement, the only newspapers were The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, which issued government proclamations and published preponderate views in line with the Governor’s opinion.

Was there Press Freedom?

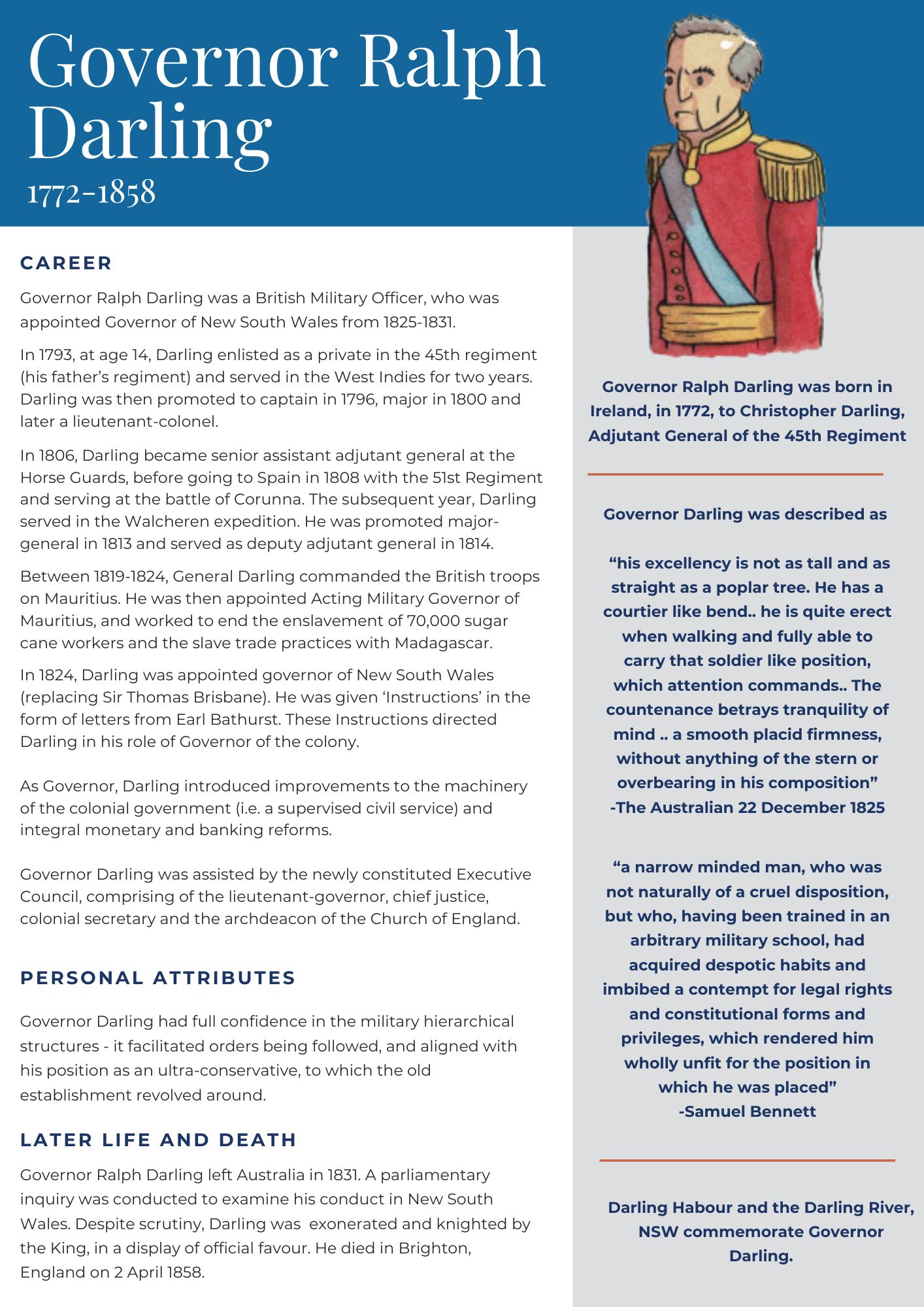

Shortly after The Australian Newspaper was established, Governor Ralph Darling attempted to introduce a Bill to regulate the flow of information through the press, believing that controlling the narrative was key to maintaining order.

Despite the growing success of the colony, Governor Darling sought to introduce a press licence to tighten control and curb potential misinformation- especially if it was about him! The licensing scheme would have allowed Darling to regulate who could publish newspapers, and ultimately, the information that could be circulated throughout the colony.

On the one hand, this may have seemed logical. The colony was largely composed of convicts and was isolated from the protection of England. Allowing a free press could potentially incite an uprising and weaken the authority of the Governor.

Governor Darling had the support of his English superiors and a similar licence had already been introduced in Tasmania. Earl Bathurst wrote to Governor Darling a few years earlier

“It is however impossible not to perceive, from the most cursory examination of [newspapers published in New South Wales], that the entire exemption of the Publishers from all restraint of the local Government, must be highly dangerous in a Society, of so peculiar a description.”

Darling argued that granting those with a criminal past the right to express their opinions was too risky – especially if they disagreed with those in power.

On the other hand, the colony was rooted in English law, which guaranteed certain rights to all, including the convicts.

As British subjects, they inherited the protection of the law as their birthright, including the right to express their opinions freely. This was articulated in Volume 4 of the Blackstone Commentaries, that were brought to NSW on the First Fleet:

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state: but this consists in laying no prior restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.”

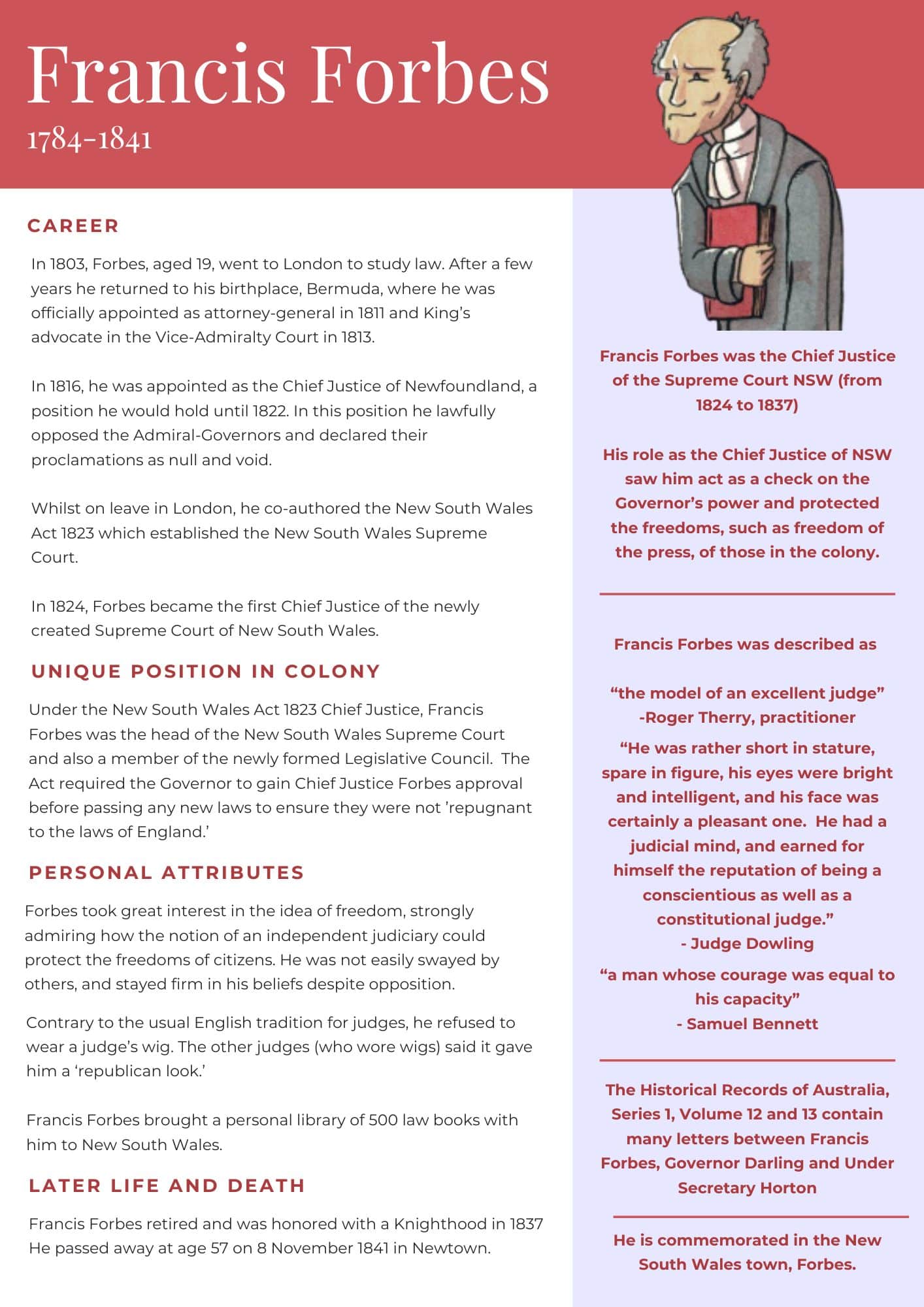

Chief Justice Forbes, the first Chief Justice of the newly established Supreme Court of New South Wales had the power to strike down any laws that were ‘repugant to the laws of England.’ He ruled that freedom of the press was a constitutional privilege. He struck down Darling’s law as repugnant. He believed in the rule of law and recognised that a free press promotes transparency, holds those in power accountable and prevents the public’s interests from being overlooked or manipulated. Restricting freedom of speech and the flow of information would pose a greater threat to the stability of the colony than allowing open discussion. Protecting this freedom was not, therefore, only a matter of principle but was a necessity for the ongoing health of the growing nation.

In his letter to Lord Bathurst on 11 May 1827, Chief Justice Forbes wrote:

“By the laws of England… every free man has the right of using the common trade of printing and publishing newspapers; by the proposed bill this right is confined to such persons only as the Governor may deem proper.

By the laws of England, the liberty of the press is regarded as a constitutional privilege, which liberty consists in exemption from previous restraint; by the proposed bill, a preliminary licence is required which is to destroy the freedom of the press and to place it at the discretion of the Government.. by the laws of England .. every man enjoys the right of being heard before he can be condemned either in his person or property… [by the proposed bill] the Governor, with the advice of the Executive, may revoke the licence granted to any publisher at discretion, and deprive the subject of his trade, without his having the means of knowing what may be the charge against him, who may be his accuser, upon what evidence he is to be tried, for what violation of the law he is condemned.

The Governor and Council may be both complainants and judges at the same time, and in their own cause—-that cause one of political opposition to their own measures, and consequently their own interests, of all others the most likely to enter into their feelings and influence their judgment.”

The legacy of the free press in Australia can be traced back to the fortitude of Chief Justice Forbes who believed in the ancient rights of all people to have the liberty of being heard before they can be condemned!

Resources for Students

The story of Checks and Balances: Press Freedom and an Independent Judiciary is a story of the tension between Governor Ralph Darling, who had been sent to the colony to rebuild it as a place of ‘terror’ for the convicts who had been sentenced there, and Chief Justice Forbes, whose duty it was to administer justice through the courts and ensure that the rule of law was upheld by all… even the Governor! This book highlights the important role that checks and balances such as an independent judiciary and free press had in the new colony.

Case Method for History Students: Francis Forbes and the Establishment of the NSW Supreme Court

“If you were Chief Justice Forbes in the early colony of NSW that was filled with convicts, would you allow a free press?”

These resources help teachers use the Case Method to look at a historical dilemmas from the past to develop an understanding of current civic concepts.

These resources, all have printable PDF’s and include:

-

- Case Summary: The Story lets history unfold in the present

- Case Exhibits: Primary Source documents that provide students with an insight into the information available to decision-makers at the time and are read prior to class

- Exhibit 1: Source Documents on Governor Ralph Darling and Chief Justice Forbes

- Exhibit 2: Source Documents on Freedom of the Press

- Exhibit 3: Source Documents on the Sudds and Thompson incident

- Discussion questions: That the teacher can use to prompt class discussion

- The Outcome