Experiences of women on the First Fleet voyage: Susannah Kable

Background

In 1784, Susannah Holmes, a 19-year old English girl from a poor family, was found guilty of stealing bed sheets, cloth and household items from her employer, Jabez Taylor.

These years were difficult for the poor due to the decline of the wool trade in Norfolk and Suffolk and the loss of common grazing land resulting from the enclosure laws enacted from 1750.

Susannah was prescribed the death penalty – but due to her young age – her sentence was reprieved and changed to transportation to ‘some of Your Majesty’s Colonies or Plantations in America’ for a term of 14 years.

But the American War of Independence (that had been ongoing since 1775) had halted convict transportation to America, so Susannah was imprisoned in Norwich Castle Gaol for three years, whilst awaiting transportation.

Conditions in Norwich Castle Gaol

Conditions in Norwich Castle Gaol

The conditions in Norwich Castle Gaol were horrible. It was a disease-ridden, unsanitary prison, which was sweltering in summer and ice-cold in winter. Prisoners were housed in rough shelters built against the castle walls; it was overcrowded, and food supplies were limited. By 1786, overcrowding in English gaols had become so severe that local people even petitioned the government to address the problem.

In these dire prison conditions, Susannah met another inmate, Henry Kable, formed a relationship and gave birth to their first child, a baby boy named Henry Jr, in 1786.

The government desperately needed a new destination to send all these convicts. They decided on Botany Bay as the destination for the new penal colony of New South Wales and began preparations for a fleet of ships to transport 750 convicts there. This new colony would be under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip. The home office under Lord Sydney started to collect convicts in prison hulks at three locations: the Thames, Portsmouth and Plymouth.

In October 1786, the Home Secretary directed the removal of Susannah and two other women, Elizabeth Pulley and Hannah Turner, to the hulk, Dunkirk in Plymouth.

According to the Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday November 11, 1786:

One of the “unfortunate females was the mother of an infant about five months old, a very fine babe, whom she had suckled from birth.”

The young family was torn apart.

Separation of Henry Jr from Susannah

On the 5th of November 1786, Susannah and her baby were taken from the Gaol to board the prison hulk Dunkirk moored at Plymouth – which served as a collection point for prisoners from various gaols being assembled for the First Fleet.

However, as Susannah neared the ship, the captain refused to take her baby on board, claiming he had no lawful authority to do so, so the mother and child were cruelly separated.

The Norfolk Chronicle at the time read

“The frantic mother was led to her cell execrating the cruelty of the man and vowing to put an end to her own life.”

Conditions aboard the prison hulk Dunkirk

Conditions aboard Dunkirk were likewise bleak. Another convict, Bryant from Cornwall – who was convicted for highway robbery, spent time on the Dunkirk while awaiting transportation to NSW, and documented the conditions aboard the vessel:

“A derelict ship, it’s mast gone, it’s sides covered in green slime lay mired in a mudbank. This was the prison ship Dunkirk. The convicts smelled the hulk before they saw her, for she reeked of sewage and the foul stench of decaying wood and unwashed humanity. Towering over the surrounding flats, her hull blackened with mire, the hulk Dunkirk loomed up before the approaching convicts like an apparition. A dark and spectral form around which the rising tide began to lap.”

Conditions were so appalling aboard the Dunkirk hulk that the officer in charge even complained that “many of the prisoners are nearly if not quite naked.” And in 1784, the abuse of female convicts by the marine guards even led to a ‘Code of Orders’ being drawn up to protect the women.

The ‘humane gaoler’

Meanwhile, the Norwich prison turnkey, John Simpson had been left with Susannah’s baby.

The Gaoler took sympathy on the young family. He travelled to London, nursing Henry Jnr on his lap and persuaded Lord Sydney – to permit the child’s father, Henry and the baby to join Susannah in the new penal colony.

Simpson took the news back to Henry at Norwich and promptly escorted him to the ship at Plymouth.

The story of the ‘humane gaoler’ who selflessly fought to reunite a convict family – attracted the press’ attention and spread all over London.

The story gained overwhelming support, and a public collection was made. A substantial sum of £20 (nearly twice the annual salary of a labourer at the time) was raised for a parcel of items containing clothes, books, and tools to be given to Susannah and Henry for their new life in New South Wales.

The Kables’ parcel of goods was loaded on the transport cargo ship, the Alexander, under the care of the ship’s captain, Duncan Sinclair. The Kables were to collect their parcel at the end of their journey.

Convict experiences during transportation

After around 6 months enduring the horrible conditions aboard the prison hulk Dunkirk, the three of them – Henry, Susannah and their baby – finally embarked on the Friendship, setting sail on the 11th March 1787.

At Cape Town, Susannah was transferred to the Charlotte, to make room for a cargo of sheep.

The fleet sailed from Cape Town on the 12th of November, but once at sea, unfavourable winds drove the fleet West. In response, Governor Philip decided to divide the fleet into two divisions: a faster division, which included the Friendship, and a slower division, which included the Charlotte.

As a result, Henry and Susannah found themselves travelling in different divisions, and naturally, they would have been anxious about each other’s fate during the treacherous passage across the Southern Ocean.

Jonathan King, writing in The First Fleet (1982), claimed about this part of the journey:

“This leg of the journey was also terrible for the convicts as great seas crashed into their quarters wetting them through and continual squalls tossed them about in their crowded cells. The hatches had to be battened down a lot of the time so the stench below was worse and there was little chance of the convicts drying off, taking exercise or keeping warm. The extreme cold from the southerly latitudes increased their misery and when the fuel ran out there were no more cooked meals to cheer them up or fight off the inevitable diseases.”

The First Fleet consisted of: Around 850 convicts and their Marine guards and officers, led by Governor Arthur Phillip.

11 British tall ships – 6 convict transports, 3 store ships and 2 naval escorts.

Convict experiences in the early British penal colony of New South Wales

The First Fleet initially arrived in Botany Bay on the 18th of January, but it was promptly deemed unsuitable for settlement due to its poor soil and lack of freshwater sources.

So, instead the First Fleet sailed into Port Jackson (Sydney Cove, known as Warrane to the Gadigal clan) on the 26th of January 1788.

The journey from England to Australia had taken 252 days and during the voyage around 48 people had died (a mortality rate of about 3%, compared to 26% who died on the voyage aboard the Second Fleet).

Susannah and Henry, along with four other couples, were married by the Reverend Johnson a few days later on 10 February 1788.

Hardship in the Early Colony

The early years of the colony at Sydney Cove were marked by severe hardship. There was extreme famine, with food supplies dwindling as they struggled to harvest the land agriculturally and were forced to rely on the limited provisions shipped on the First Fleet. Their storehouses were ransacked by rats and rotten. Tight rations were imposed as they desperately awaited the Second Fleet (which only arrived in June 1790 – a whole 2 years later!). There was widespread starvation and high mortality.

As the diarist Captain-Lieutenant Watkin Tench wrote in A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales (1793):

“Famine besides was approaching with gigantic strides, and gloom and dejection overspread every countenance.”

For the first few months in the new British penal colony, shelter was in tents and primitive.

Convicts were forced to work, and if they resisted, they could be subject to harsh punishments – including lashings, forced labour in chain gains and solitary confinement. Two common punishments involved: 50 lashings (via the cat o’nine tails; a multi-tailed whip with lead weights) or performing backbreaking work in chain gains (with irons weighing 4.5kg or more shackled together around their ankles).

Whilst this dreadful image of hardship and ruthless discipline is often the impression we have of the early colony, convicts also enjoyable considerable freedoms that they did not have in England.

Increased freedoms & opportunities

“A gulag, where men and women simply worked and wither in useless and remote isolation, was not intended- not by the administration and certainly not by [Governor] Phillip” – Michael Pembroke in Arthur Philip: Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy (2013).

As the historian John Hirst argued in Australian History in 7 Questions (2014), quickly this new settlement began to look something like a “republic of convicts.”

While the official rule was that convicts were to work from sunrise to sunset, Monday to Saturday – the convicts who oversaw the work of other conflicts implemented their own system. Convicts were given a daily task (e.g. Such as felling a certain number of trees) and once complete, convicts were free to leave – often by midday.

During their free time, convicts could laze about, steal, or take on additional paid work. It took years for governors to reclaim some of this afternoon time. In 1814, Governor Macquarie declared that convicts had to work the full day for their private masters, but masters were required to pay for work done after three o’clock.

Due to the hardship of getting free people to come to the colony to perform these tasks – the governors drew on the convicts for all professional services. There were convict lawyers, architects, surveyors, doctors, teachers, artists – and even police!

Early governors were given no specific instructions on convict punishment. They readily granted pardons to those who did good service, as well as to those who received recommendations from home in Britain. ‘Tickets of leave’ became a reward for good behaviour.

Convict servants assigned to officers, who ventured into trading, initially ran their shops. But over time, these convicts set up their own business, becoming traders, shipbuilders and bankers.

Further, upon gaining their freedom, convicts were granted thirty acres as a farm and convict servants to help them work it. Some ex-convicts even went on to wealthy landowners.

A second stage in the colony’s history: The attempt to make it into a proper penal colony

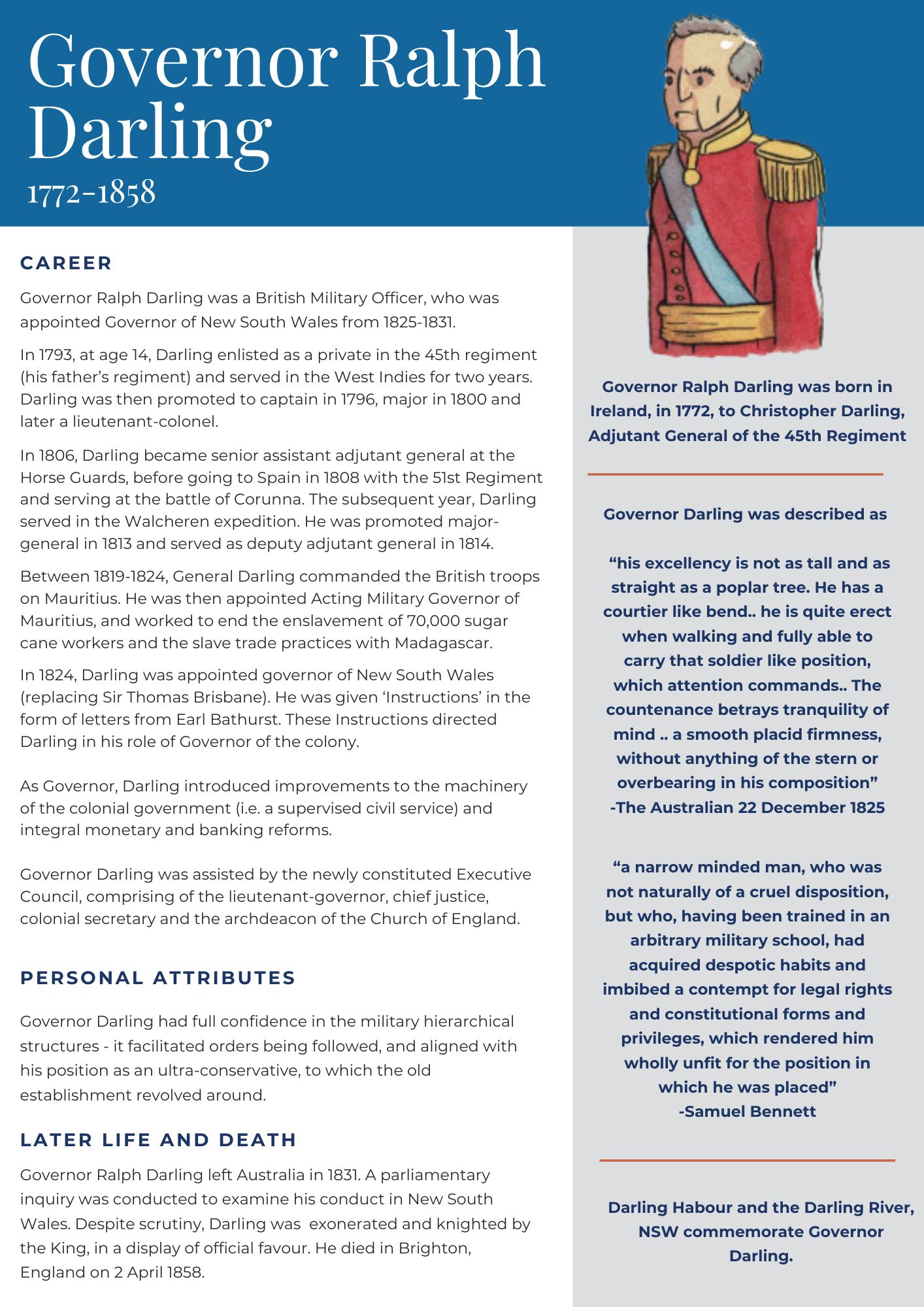

BIGGE REPORTS: The British government sent a commissioner of enquire, John Bigge to NSW in 1819. He was to determine how to make New South Wales a fit place for punishment, both for deterrence and reformation. Bigge’s recommendations were adopted by the British government and carried out by Governor Brisbane (1821-1825) and Governor Darling (1825-1931).

*For more information on this – check out our storybook, ‘Checks and Balances: Press Freedom and an Independent Judiciary’ and accompanying resources.

Status of convicts as ‘dead to the law’ in the British penal colony of New South Wales

The First Charter of Justice (1787) included the establishment of a judicial system in NSW based on English law.

However, under English law, convicts were considered ‘dead to the law’, meaning they were unable to access the protections provided by the law. This included the inability to give evidence, bring actions in court, or to take legal action to protect their property. In a colony of convicts, if applied, this would have significant implications, effectively excluding more than half of the population from pursuing legal action.

As Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-1769) put it:

“A felon is [considered] no longer fit to live upon the earth…to be exterminated as monster and a bane to society…he is already dead in law.”

Their case

Their case

The Kables’ parcel of goods had been loaded onto transport cargo ship, the ‘Alexander’, under the care of the ship’s captain, Duncan Sinclair. The Kables were to collect their parcel at the end of their journey.

But when they inquired about their parcel of goods, to their shock, it could not be found, and the ship’s master dismissed their pleas for help. Susannah and Henry were young and could not read or write, with no family, possessions or rights in this new penal colony. The parcel held their hopes for their new life and it had now gone missing.

Susannah and Henry, likely with the help of Reverend Johnson, lodged a claim for their lost parcel in July of 1788, suing the shipmaster of the Alexander for the loss of the goods en route.

On the first of July 1788, a writ in the names of Henry and Susannah Kable was issued from the new Court of Civil jurisdiction in NSW. The writ recited that the parcel loaded onto the Alexander had not been delivered to the Kables in Sydney despite many requests, and sought delivery of the parcel, or its value. It named the ships captain, Duncan Sinclair, as defendant. The court, consisting of Judge-Advocate David Collins and two civilians issued a warrant to the Provost marshall ordering him to bring the captain before the court the next day to answer the complaint against him.

In bringing their case before the civil court, Susannah and Henry’s position as ‘dead before the law’ was ignored. In the claim, the Kable’s occupation of ‘new settlers’ was crossed out and left blank. While ‘convict’ was a more correct legal term, writing this could have been detrimental to their case and prevented them from bringing the action in court.

Susannah and Henry signed the document with an X as neither could write their name.

The Case was heard in the NSW Civil Court (which at the time did not have a Courthouse) by 3 independent persons, with eyewitness accounts and statements.

Ultimately, the Kables’ won their case, receiving fifteen pounds compensation. This action was the first civil court case in the new penal colony.

Legacy

Legacy

This case was greatly significant, demonstrating the rule of law in operation, as the poor convict Kable family were treated as equals under the law, despite the vast difference in their status and wealth compared to the powerful Captain Sinclair.

The Kable’s case set an important legal precedent relevant to Australia today – emphasising that the protections of the law must be applied equally and fairly to all.

This legal principle allowed convicts (like Susannah and Henry), who had been previously considered ‘dead to the law’, to own property and seek legal protection.

Henry later became the Chief Constable and had various successful business ventures including a fleet of ships and a brewery. Susannah and Henry further went on to have 10 more children, with their descendants still contributing to Australian society today.

The story of Susannah and Henry underscores the enduring importance of having the protection of the rule of law where no-one is above the law, both for the convicts in the penal colony and for us today.

Resources for Students

The story of Checks and Balances: Press Freedom and an Independent Judiciary is a story of the tension between Governor Ralph Darling, who had been sent to the colony to rebuild it as a place of ‘terror’ for the convicts who had been sentenced there, and Chief Justice Forbes, whose duty it was to administer justice through the courts and ensure that the rule of law was upheld by all… even the Governor! This book highlights the important role that checks and balances such as an independent judiciary and free press had in the new colony.

Case Method for History Students: Francis Forbes and the Establishment of the NSW Supreme Court

“If you were Chief Justice Forbes in the early colony of NSW that was filled with convicts, would you allow a free press?”

These resources help teachers use the Case Method to look at a historical dilemmas from the past to develop an understanding of current civic concepts.

These resources, all have printable PDF’s and include:

-

- Case Summary: The Story lets history unfold in the present

- Case Exhibits: Primary Source documents that provide students with an insight into the information available to decision-makers at the time and are read prior to class

- Exhibit 1: Source Documents on Governor Ralph Darling and Chief Justice Forbes

- Exhibit 2: Source Documents on Freedom of the Press

- Exhibit 3: Source Documents on the Sudds and Thompson incident

- Discussion questions: That the teacher can use to prompt class discussion

- The Outcome