Kulwinder Singh Case Note

The Crown alleged that Mr Singh had poured accelerant on his wife, Kaur, deliberately setting her alight with the intention of causing her serious harm, if not death. He endured 2 trials ending with a finding of not guilty and then in 2023 received costs for both trials, where the Her Honour stated “I am satisfied that it was not reasonable for the prosecution to commence proceedings for murder against Mr Singh”.

This case note looks at the presumption of innocence, evidence, the role of juries to deliver fair outcomes and whether justice is achieved when the accused is acquitted after a lengthy period of time.

In a multicultural society with varied cultural norms, can the legal system maintain impartiality throughout investigation and trial processes? How does the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) determine what cases will be prosecuted? What role does evidence play in proving a case? Can juries deliver fair outcomes when they may have encountered the details of a case before empanelment? Is justice still achieved when an accused person is acquitted after a lengthy period of time spent in the system?

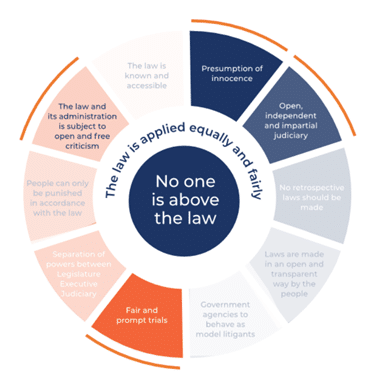

The case of Kulwinder Singh shows the importance of adherence to long established procedures in achieving rule of law principles and upholding the rights of the accused. Of particular importance are the principles of presumption of innocence (particularly through the investigation process and committal processes) and fair and prompt trials. This case also demonstrates how the legal system recognises the burden to acquitted persons of lengthy proceedings through the creation of legislation enabling cost recovery in cases that have been acquitted.

The presumption of innocence and the achievement of fair and prompt trials are principles of the rule of law. Click here to find out more

Case Citations

A full summary of the facts, evidence, and tests of admissible evidence can be found in parts 1-5, 28-29 and 40-52 in the judgement for cost at nsw.gov.au case citation:

R v Singh (No 8) [2023] NSWSC 51

A video of Mr Singh’s evidence can be found at:

**Please note that this video contains distressing scenes and will not be suitable for all audiences**

Click to Jump to Section

Facts of the case

Married by arrangement in India in 2005, husband Kulwinder Singh (‘the accused’) and wife, Parwinder Kaur (‘the deceased’) were both of the Sikh faith. Mr Singh already lived in Australia, and Ms Kaur emigrated in the middle of 2006 to live with her husband. Initially, they lived with Mr Singh’s parents in Kellyville, the couple eventually building a house in Rouse Hill in 2011.

Finances became a source of contention between the couple, and Ms Kaur eventually established a separate savings account in her own name that she directed her employer to switch wage payments into rather than into the mortgage account, escalating tensions between them.

On 2 December 2013, Both Mr Singh and Ms Kaur attended their places of work in the morning, with Ms Kaur arriving home around 11.30am and watching a movie. At around 1pm, Mr Singh arrived home. He asked her to resume making contributions to the mortgage and the deceased refused, after which he made statements that he was packing bags to go to his mother’s home for a few days.

That had caused an argument.

According to court records, Ms Kaur then called her brother briefly at 2.04pm to say that she had argued with her husband about money. Her brother was unconcerned by this call, telling her he would speak to her when he finished work. She then called to 000 at 2.07pm, saying “my husband nearly kill me.”

Following these two calls, Ms Kaur was witnessed by neighbours running down the driveway of their Rouse Hill home engulfed in flames, with Mr Singh chasing her and attempting to pat out the flames with his hands.

Neighbours, police and ambulance officers arrived at the crime scene shortly after. The deceased, Ms Kaur, was still conscious when she fell to the ground at the end of her driveway. When police and ambulance officers arrived at the scene, Ms Kaur was asked more than once: “Did your husband do this to you?”, but she did not implicate her husband at any time.

Ms Kaur had sustained burns to almost 90% of her body, but her scalp, long hair and most of her face remained untouched. She passed away the following day.

Investigative History

Detectives from the Hills Local Area Command and the State Crime Command’s Homicide Squad formed Strike Force Whyalla in December 2013 to investigate Ms Kaur’s death. During the investigation, a forensic search of the home was conducted, which discovered:

- The fire had started in the laundry room at the rear of the house

- A cigarette lighter and a can of petrol were located in the laundry with only Ms Kaur’s fingerprints and DNA on them. No DNA or fingerprint evidence of Mr Singh was found on those items or in the laundry room

- No fuel was found on Mr Singh’s clothing

- There were some small traces of spattered accelerant on the laundry floor

There were no third party witnesses to the events, and Mr Singh was interviewed by police a number of times during the investigation.

“He told police that the couple had argued about money, and he decided to stay with his mother. He packed some clothing and was walking up and down the stairs near the front of the house, carrying the bags to his car. At one stage, he heard a scream and ran out of the front door where he saw his wife in flames. He denied setting her on fire.”

Adams J, R v Singh (No 8) [2023] NSWSC 51 at [3]

Procedural History

Following widespread media interest, the case was referred to the NSW Coroner and an inquest was held into Ms Kaur’s death. On 27 November 2015, Deputy State Coroner Freund suspended the inquest, stating that a ‘known person’ committed an indictable offence and that “it was possible that a jury would convict that known person.” Click here to learn more about the Coroners Court.

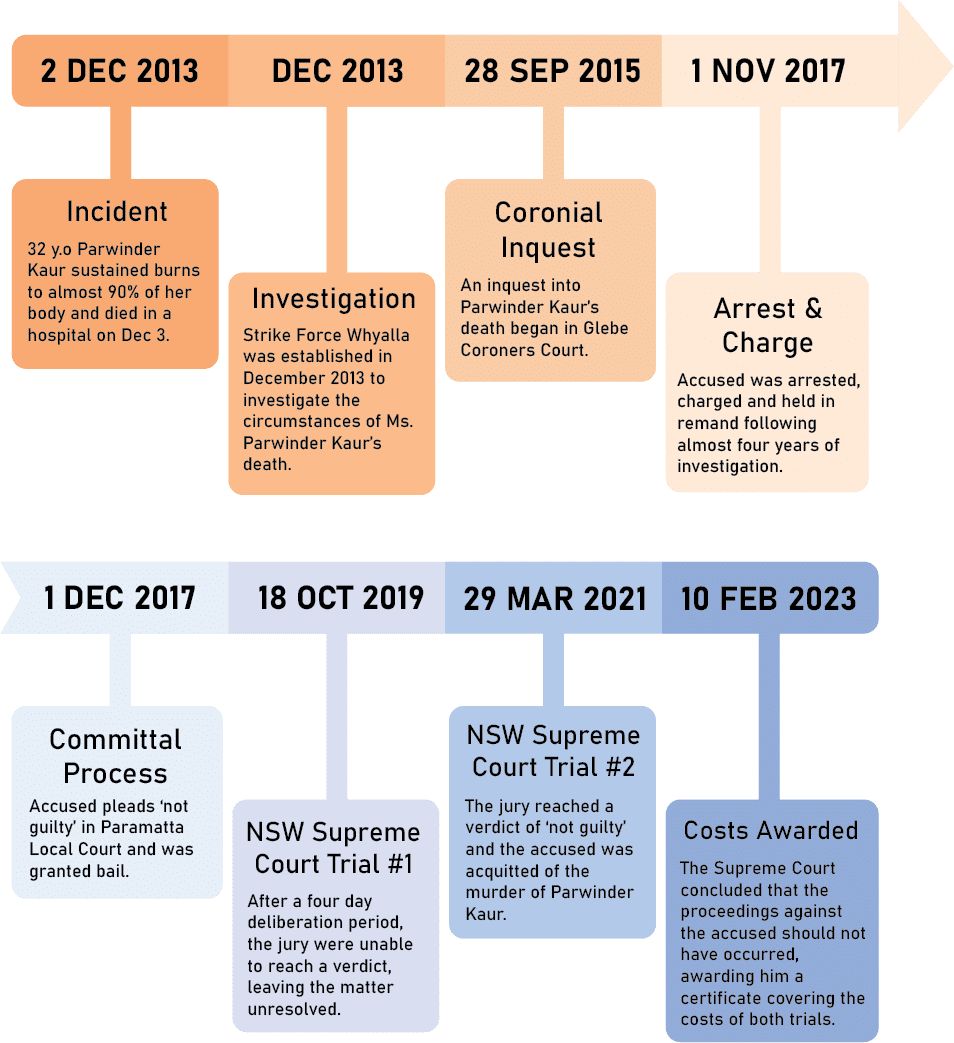

The matter was then referred to the ODPP in accordance with Sections 78(1)(b), 3(b) and 4 of the Coroner’s Act 2009 (NSW). The accused was arrested and charged with his wife’s murder on November 1, 2017. By this stage, a period of almost four years had elapsed since the incident at the couple’s Rouse Hill home.

The accused was held on remand before being granted bail on 1 December 2017 during his committal hearing by Magistrate Tsavdaridis in the Parramatta Local Court.

His first trial commenced on August 12, 2019, and was heard before Justice Adams of the NSW Supreme Court and a jury of 12 persons. The Crown alleged that Mr Singh had poured accelerant on his wife, Kaur, deliberately setting her alight with the intention of causing her serious harm, if not death. This trial ended with a hung jury on October 18, 2019.

A second trial before Justice Adams commenced on 18 February 2021, again with a jury of 12. On 30 March 2021, after approximately an hour of deliberation, the second jury, returned a verdict of not guilty.

In June 2021, solicitors for Mr Singh advised Justice Adams that they would make an application under the Costs in Criminal Cases Act 1967 (NSW), to recover from the NSW Government the costs incurred by Mr Singh in his defence, speculated to be approximately $1 million.

Justice Adams heard submissions on 2 September 2022. On 10 February 2023, Her Honour made an order that the NSW Government should pay the costs accrued by Mr Singh in defence at both the 2019 and 2021 murder trials.

Figure 1: Timeline of the Singh Case

Key Case Elements and Rule of Law Principles

Several important questions that challenge the fairness of the legal system and its processes are raised when examining this case:

- Why did the initial police investigation take so long?

- What sparked the Coronial inquest?

- Was the DPP behaving in accordance with the Prosecution Guidelines?

- What is an appropriate level of interaction between the media and the public so that an accused’s right to a fair trial is not compromised?

- Why did the entire process take so long from start to finish?

- Was Mr Singh denied the right to a prompt and fair trial?

- What options are available to accused persons after a ‘not guilty’ verdict that has taken so long to reach?

Presumption of Innocence

One of the foundations of our legal system and a key rule of law principle is that all people, regardless of their cultural background, history or social standing, are equal before the law. The presumption of innocence, or the right to be innocent until proven guilty, supports this notion of equality by offering all people the protection of the law and endowing the same right to all persons accused of all crimes, regardless of their severity, until a decision is made before a court of law.

This principle is a ‘presumption at common law’ in Australia, meaning all persons are entitled to this right, but it is not a legislated right. This right is protected by the Burden of Proof because by placing the onus (or obligation) of proof on the prosecution, the accused will remain innocent, and maintain equal status and rights to all others in this society, unless it can be proven otherwise.

In the Australian system, people cannot be convicted on an accusation; the onus is on the prosecution to prove the guilt of the accused in a court of law beyond reasonable doubt, using evidence and following rules and legal processes to establish the facts and determine the case.

The presumption of innocence is also upheld by international law in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) at Article 14(2), protecting the freedom of citizens and guarding against arbitrary accusations and imprisonment.

Non-legal responses

Media

Widespread media coverage occurred throughout the course of the police investigation, Coronial Inquest and court cases. From the outset of the incident, Ms Kaur was repeatedly depicted as a victim of domestic violence, who had suffered at the hands of her husband and his family for an extended period of time.

Figure 2: Some national and International headlines seen during the course of the case

The power of the media to influence public opinion can impact upon accused persons right to the presumption of innocence, particularly where widespread coverage over an extended period of time may be encountered by the jury pool. This may influence the effectiveness of the jury system as the ability of the jury to make impartial decisions can be eroded, impacting on just outcomes for the accused.

Blacktown Council

Following the death of Ms Kaur in 2013, Blacktown Council, where the couple resided, held a candlelight vigil to commemorate the deceased, identifying her as a victim of domestic violence. The Council, against advice, also issued a media release indicating so.

At the time, the police investigation was in its early days, and no charges had been laid against Mr Singh, nor was there any record of domestic violence or complaints of disturbances at their address from neighbours. This very public proclamation may have been encountered by potential jurors, eroding Mr Singh’s presumption of innocence as the implication that he was guilty of domestic violence and her death were clear.

Fair and prompt trials

The impact of long running cases on all parties to a case is significant. Financial, emotional, familial, and social impacts can continue long into the future, even after the conclusion of a matter. For these reasons, the rule of law requires that trials should be both fair and prompt, with Articles 9(3) and 14(3) of the ICCPR requiring that matters are dealt with promptly for individuals charged with criminal offences.

These two concepts are intertwined, particularly when evidence is reliant on individuals memories of events or investigations, as the closer the events are to the evidence being given, the more accurate the evidence will be.

In 2022, BOCSAR reported that in matters involving defendants on bail in the NSW Supreme Court, there was on average 718.5 days from arrest to finalisation of the matter where defendants were eventually acquitted. The same report found that for defendants who plead guilty, arrest to finalisation is 1,315 days. Source: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research ‘NSW Criminal Court Statistics Jul 2017-Jun 2022’

Duration of Investigation and Court proceedings

In the case of Mr Singh, the investigation of Strike Force Whyalla lasted 4 years, with subsequent proceedings continuing for another 6, not achieving a prompt resolution for the alleged offender, the victims’ family, or the witnesses to the event. This period of waiting can cause serious psychological and financial harm to the parties to a case, and can lead to lost reputations, careers, assets, incomes, and relationships.

The impacts of the lengthy investigation and proceedings on Mr Singh were evident in the committal hearing and bail application heard on December 1, 2017 When hearing the application, Magistrate Tsavdaridis took into account the opinion of forensic psychiatrist Dr Gerald Chew, who diagnosed Mr Singh with a “major depressive episode”. According to Dr Chew, Mr Singh had a “very high risk of suicide” and feared for his life in jail, and for these reasons, would be better managed in a setting outside of custody.

The Investigation Process

The police investigation was described by the media afterwards as ‘bungled’. Items that should have been bagged as evidence were not. A mobile phone was found in the laundry but it was not dusted for fingerprints. A DNA swab that was taken from a knife found in the laundry was later destroyed by police.

Mishandling of evidence and incomplete initial investigations can impact heavily on trial outcomes and fairness for both the accused and the victims. Strict protocols regarding the gathering, handling, transportation and storage of evidence exist, and rules of evidence for court proceedings are created and protected in the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW). These measures are designed to ensure that the most accurate picture of events can be generated in order to reach a just outcomes for victims and offenders.

Resource Efficiency

The death of Ms Kaur and the implication of domestic violence generated significant public interest and media coverage, with Strike Force Whyalla specifically created to investigate Ms Kaur’s death.

During their investigations, the taskforce created a number of re-enactments of the incident using members of the fire brigade and police, fire experts, forensic, technical and cultural specialists in order to understand what had occurred in the home that day. Burns experts were also consulted to analyse the burns on the body of the deceased.

Speculation over a cultural link to the manner of death may have prompted this response from police in order to understand the elements that may have played a role in the death of Ms Kaur. However, the cost of conducting an intensive 4-year investigation into a single death raises questions of equality before the law for victims of other similar crimes and the accused in this case.

Evidence and the decision to prosecute

In court proceedings, evidence is needed to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt. Only then can a verdict of guilt be established. Under the Director of Public Prosecutions Act 1986 (NSW), the NSW ODPP prosecutes indictable offences and issues guidelines that outline the conditions for the commencement and conduct of criminal prosecutions.

The decision to prosecute involves two questions:

1. Is there a reasonable prospect of conviction on the admissible evidence?

2. Is a prosecution in the public interest?

Evidence

A large amount of evidence was tendered to the court in the Singh case, including physical, written and circumstantial evidence, and witness testimony.

Physical Evidence

Key pieces of evidence pointing to the innocence of the accused were:

- A knife. A DNA swab identified fingerprints of the deceased and an ‘unknown male’. The accused had supplied his DNA early in the investigation and was not linked to the knife. However, this evidence was destroyed during the investigation.

- A petrol can. Ten of the deceased’s fingerprints were found on this item, but none of the accused. There was no evidence of the can being wiped clean. The arrangement of the cluster of fingerprints on the can were consistent with a self-pour (whoever was holding the can most likely poured petrol on themselves). The petrol can, still containing 1 ¼ litres of fuel, was closed and placed back in the cupboard with the door closed.

- Small traces of petrol were found in the laundry, but no evidence of petrol splashes in or around the room.

- A cigarette lighter with the deceased’s right index and ring finger’s prints on it and none of the accused.

- The accused’s clothing. No traces of petrol were found at all on the accused’s clothing or on his sandals.

- The deceased’s clothing. Contrasted with the weather, the deceased wearing a knitted acrylic cardigan over her singlet top. The cardigan was made of a highly flammable material. Petrol was found on the deceased’s clothing.

- A wet cotton towel. Found in the bedroom of the couple’s home and containing traces of the deceased’s DNA. The deceased’s hair, scalp and face were completely preserved, despite severe burn to most of her body.

Circumstantial evidence

Some of the circumstantial evidence that was considered in the case was:

- The telephone call made by the deceased to Triple-0. It was an 89 second call, there was no noise in the background and the deceased sounded calm. She gave and spelled her name and address, and during call, told the operator: “My husband nearly kill me”. The operator asked: “What did he do to you?”, but the deceased gave no response.

- The call made by the deceased to her brother 9 seconds immediately prior to the Triple-0 call. During that call, the deceased told her brother the accused was asking for money. The deceased’s brother told the deceased he couldn’t talk to her because he was at work, but he would call her later.

- The movie ‘Gadar’ found in the DVD player. The movie depicted the story of a woman with beautiful hair whose family were in dispute with her husband. At the end, they were reunited over the woman’s hospital bed after an accident, which provided a happy ending.

Witness Testimony

- The mother and sister of the accused both gave evidence about arguments between the accused and the deceased about their finances.

- The deceased’s sister gave evidence that the accused had told her: ”If she [Parwinder Kaur] says she will divorce me, I won’t let that happen. We kill people and nobody can find out.”

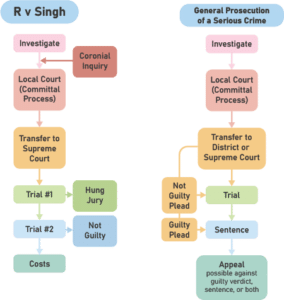

Figure 3: The steps taken in the prosecution of serious crimes and the steps taken in the R v Singh case

The Decision to Prosecute

The NSW criminal justice system’s overarching purpose is to achieve justice, and uphold fairness for victims, accused persons, offenders and society. However, balancing the needs of parties with competing interests while maintaining public confidence in the justice system is challenging, particularly where there are prominent social issues implicated in a case, such as domestic violence.

Key pieces of physical and circumstantial evidence suggest that the Singh case should not have proceeded to trial, a view also given in a report tendered to the Coronial Inquiry by the detective in charge of the case and reflected by Justice Adams during her findings for costs in February 2023. In her judgement, Her Honour stated:

“It is hardly surprising that police would initially suspect Mr Singh of killing his wife. He was the only other person in the house at the time and the prospect that Ms Kaur deliberately burned herself must have seemed incomprehensible.

But the physical evidence overwhelmingly pointed to Ms Kaur being the one who poured the accelerant on herself and ignited it some time later. The evidence as to the plot of the film she was watching immediately prior to doing so confirms other aspects of the physical evidence that, tragically, that is what most likely occurred.

Having regard to all of the relevant facts, I am satisfied that it was not reasonable for the prosecution to commence proceedings for murder against Mr Singh for the reasons I have just provided.”

Adams J, R v Singh (No 8) [2023] NSWSC 51 at [95]

However, given the public perception of the circumstances of this case, and instances of serious, ongoing domestic violence, including ‘honour killings’ in Sikh culture overseas being reported, there may have been pressure on the ODPP to continue with the prosecution to placate the public. This would have created a public perception of justice for the perceived victim of an horrific crime, however, has immeasurably impacted on a just outcome for the accused.

The law and its administration is open to open and free criticism

In the creation of a mechanism that enables acquitted persons to seek recourse for their costs in defending cases, the rule of law principle that requires the law be subject to open and free criticism has also been fulfilled.

As seen above in Justice Adams comments, which are publicly available, the administration of the law by the ODPP has been critically assessed in an open and transparent way that may lead to positive procedural changes in the future, better outcomes for persons under investigation and the improved achievement of the rule of law.

Rejection of an expert witness

“I have to ensure that both the prosecution and Mr Singh receive a fair trial. At some times during the trial… I will ask the 12 of you to go with the court officer back to the jury room so that… legal issues can be discussed…to ensure that only admissible, relevant evidence is before you…”

Adams J, R v Singh [2021] NSWSC (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Supreme Court of NSW)

For more information on admissible evidence, see our resources here.

During the first trial, a test called a ‘voir dire’ (French for ‘to speak the truth’) was conducted to determine the admissibility of the evidence of a cultural expert, Ms Jatinder Kaur (a coincidental surname).

A voir dire is one of the many checks and balances during the criminal trial process that ensures the accused will be given a fair trial by testing the validity of evidence. It takes place without the jury and is designed to ensure that evidence to be put to a jury will not cause unfair bias. After hearing arguments from both sides, the judge will determine whether the evidence in question is admissible or not.

In the Singh case, the Crown had sought to admit the report of Ms Kaur, which addressed various cultural, religious and behavioural elements of relationships in Indian-Punjabi culture and the Sikh religion. The Crown also wanted to call Ms Kaur to give evidence at the trial to assist the jury to understand the cultural relevance of events potentially leading to Parwinder Kaur’s death.

A two day voir dire was conducted to determine whether she should be allowed to give evidence based on her specialised cultural knowledge. The Crown insisted she could give cultural insights and the defence objected on a number of grounds, particularly the possibility of her evidence creating unfair prejudice and bias towards the accused based on cultural generalisations. This would have the effect of eroding his presumption of innocence.

Her Honour Justice Adams found on 8 August, 2019, that the evidence of Ms Kaur was inadmissible as there was a risk of unfair prejudice occurring and denied that the evidence could be put to the jury.

“…there is a real danger that…If a jury is composed of people who do not have any knowledge of the Sikh culture …that they would misuse evidence given by a domestic violence expert that Indian women are treated as “second class citizens”. That is, there is a real risk that …the jury would rely on the evidence as a form of cultural tendency evidence.

Portions of Ms Kaur’s report …include evidence that “[t]he patriarchal beliefs related to domestic and family violence are based around a notion “to maintain their power, husband will resort to abusing their wives.”…is not only generalised… it is also highly prejudicial. I am satisfied that there is a real risk that the admission of such evidence could lead the jury [to] reasoning that because aspects of Indian/Punjabi Sikh culture might lead men to abuse their wives, then the accused was more likely to have abused his wife…

…I am satisfied that there is a real risk that the evidence would be used by the jury as expert evidence that he is in fact guilty….”

Adams J, R v Singh [2021] NSWSC at [140, 141, and 145]

Conclusion

Just outcomes rely on the achievement of key rule of law principles and the application of common law measures to achieve these, such as the presumption of innocence and the burden of proof. If these are not applied as intended, the consequences for accused persons can be substantial.

Discussion Questions

- How reliable is witness evidence after so much time has elapsed between a crime and a trial? How reliable is the testimony of family and friends of either party?

- “Justice delayed is justice denied.” Was Mr Singh’s experience consistent with Rule of Law principles?

- Could the policy of being ‘tough on crime’ eroded Mr Singh’s presumption of innocence?

- Are the mechanisms in place to ensure ‘justice is blind’ effective?

- What protections does the system offer when injustices occur due to failures of the investigation process?

- Given the potentially significant cost of the investigation, trials, and paying Mr Singh’s costs, create a mind map of alternative ways that the money could have been allocated in the justice system to improve outcomes and the achievement of rule of law principles for others.

Further Information

A full summary of the facts, evidence, and tests of admissible evidence can be found in parts 1-5, 28-29 and 40-52 in the judgement for cost at nsw.gov.au case citation:

R v Singh (No 8) [2023] NSWSC 51

A video of Mr Singh’s evidence can be found at:

**Please note that this video contains distressing scenes and will not be suitable for all audiences**

Media articles:

https://www.thesenior.com.au/story/6387859/mans-prerogative-to-hit-wife-jury-told/

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10112474/wife-las-words-fire-murder-husband/