An introduction to bail and the bail process

Bail is the process whereby a person accused of offences is released into the community while awaiting their trial. Bail usually has a number of conditions for the accused to either fulfill certain obligations, such as reporting to a police station at regular intervals, or to prevent certain behaviours, such as visiting particular places or contacting witnesses. Bail plays an important role in upholding the rights of the accused and supporting the presumption of innocence as it provides an avenue for accused persons to not be detained while awaiting trial, which can be a significant time lag.

What is bail?

Bail is an assurance that an accused person will appear at court at designated times and that they will cease offending while they are awaiting their trial. It is a written agreement between the accused and the courts or police that specifies that they can be free in the community, provided they adhere to certain conditions. These conditions might include:

- having a curfew

- staying away from particular people or places

- reporting to a police station at regular intervals

- appearing at court when required

- attending rehabilitation courses

- surrendering a passport

- agreeing to pay a sum of money if the accused does not appear at court when required

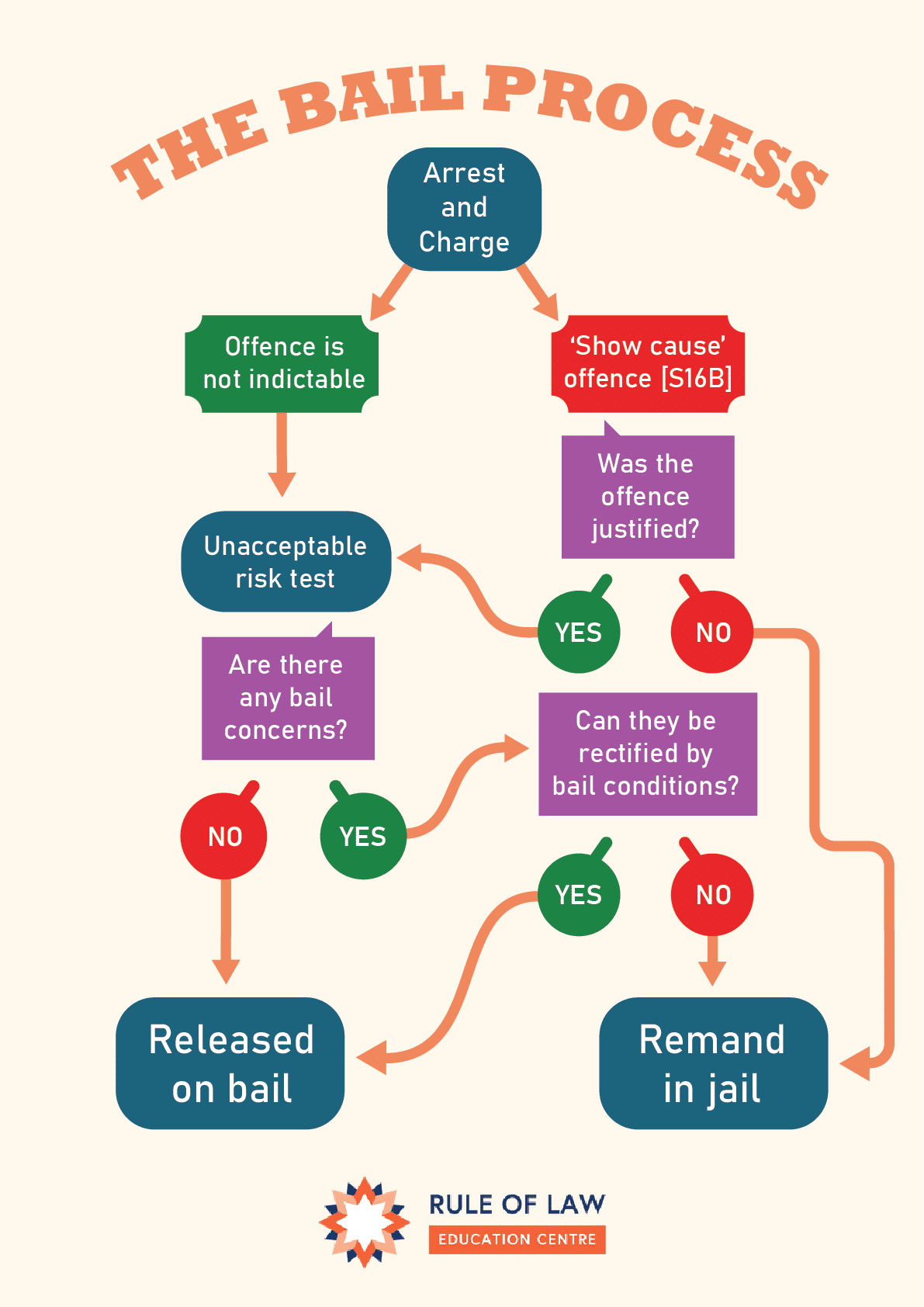

The bail process

After an individual is arrested and charged with an offence, a bail authority, which may be any of the police, a magistrate or a judge, will decide if they can spend their time in the community prior to their trial or if they will be held on remand (kept in jail) under the relevant legislation. The primary considerations for deciding whether to grant bail include the safety of the community, victims and witnesses, the potential for reoffending and whether the bail applicant is likely to appear at court when required at different times throughout the criminal trial process.

What happens if a magistrate refuses bail?

In most states and territories, applicants that are refused bail can appeal or request a review by the Supreme Court. However, in Western Australia, appeals against bail decisions made by magistrates are not allowed. Instead, a new bail application must be made to the Supreme Court.

Bail is not intended as a punishment for the accused. Instead, the purpose is to evaluate whether a person can safely remain in the community without risking the safety of themselves and others around them prior to and throughout their trial process, and that they will participate in that trial process as required.

Bail Legislation across Australia

-

- Bail Act 2013 (NSW)

- Bail Act 1980 (QLD)

- Bail Act 1977 (VIC)

- Bail Act 1985 (SA)

-

- Bail Act 1982 (WA)

- Bail Act 1994 (TAS)

- Bail Act 1992 (ACT)

- Bail Act 1982 (NT)

Case Study: Bail in NSW

In NSW, Bail is regulated by the Bail Act 2013.

Under s16B of this Act, if a person arrested has been charged with a ‘show cause’ offence, for example, any serious indictable offence as listed in Part 3 and 3A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), individuals must ‘show cause’.

Show cause means the person arrested and charged must explain why being held in a correctional facility throughout the trial process is unjustified and unfair. They are essentially ‘showing cause’ for their release. If the alleged offender is under 18 at the time of the offence they do not have to show cause, even if it was serious offence.

The courts will then also identify the seriousness of the crime and any mitigating or aggravating factors such as whether the accused was already on bail or parole, as well as other considerations, such as health, family circumstance or issues of addiction to determine whether bail should be granted.

If the accused did not commit a show cause offence, then the court will automatically begin to consider bail concerns as required under Part 3, Division 2 of the Act. Section 21 states that there are special rules for offences which can result in a right to release, including fine-only offences, certain offences under the Summary Offences Act 1988 that are not excluded, or the Young Offenders Act 1997 where children under 18 years of age are dealt with by conference.

‘Bail concerns’ refer to four primary questions that must be answered as specified in s17 of the Act. These questions form part of the ‘Unacceptable Risk Test’, and include the questions as to whether:

1. the accused will attend court when they are required to;

2. the accused has committed a serious offence;

3. the accused will endanger anyone in the community; and

4. the accused will interfere with witnesses or evidence.

Sometimes bail concerns may be addressed through the implementation of bail conditions, as outlined above, such as reporting to a police officer daily or paying a certain amount of money. If these conditions are breached, the individual can have their bail revoked (cancelled).

When the answer is no to any of these four questions, it is regarded as an ‘unacceptable risk’ under s19 of the Act. If the individual fails the risk assessment, they will be denied bail and kept in custody.

March 2024 Bail Reforms in NSW

On March 21, 2024, NSW Parliament passed amendments to the Bail Act 2013. These amendments were made in response to escalating crime rates by offenders, particularly young offenders, in the commission of motor vehicle theft and serious break and enter offences. In some areas of regional NSW, such as Moree, between 2022 and 2023, break and enter offences were up to 840% higher than the state average, and motor vehicle theft up to 680% higher according to BOCSAR.

The changes to the Bail Act focussed on:

s22C: Temporary new bail test for offenders 14-18 years old

A temporary new bail test at for offenders aged between 14 and 18 charged with committing serious break and enter offences or motor vehicle offences while on bail for similar offences has been introduced. This new test requires that the bail authority must have a high degree of confidence that the young person will not commit another serious indictable offence if granted bail on the new alleged offence. This requirement is set to ‘sunset’ after 12 months, meaning that it will no longer be in force after March 21, 2025, and its effectiveness will be reviewed by the Department of Communities and Justice using data from BOCSAR.

The introduction of a new offence at s154k of the Crimes Act 1900, the ‘Post and Boast’ offence

‘Post and Boast’ is where offenders take pictures or record themselves committing offences and either broadcast it online live or post it to social media pages after the event. Offenders who are found guilty of this offence will automatically receive a 2 year penalty in addition to their sentence for the commission of the break and enter or motor vehicle theft offence. There will be a statutory review of these offences in March 2026 to determine the effectiveness at addressing the issue of post and boast offences.

June 2024 Bail Reforms in NSW

On June 20, 2024, NSW Parliament passed further amendments to the Bail Act 2013 in response to escalating rates of domestic violence offences across NSW and Australia. A June 2024 BOCSAR report into Domestic and Family Violence shows:

- intimate partner violence accounts for 54% of all domestic violence offences;

- 73% of domestic assault perpetrators are male;

- Total domestic assault numbers for the 12 months to March 2024 rose from 34,610 to 36, 513, particularly in the Coffs Harbour – Grafton (14.2%), Hunter Valley (excl. Newcastle) (11.4%) and the Inner West – Sydney (8.9%) command areas;

- Domestic violence murders in NSW increased over the 12-month period to March 2024 from 20 deaths (Apr ‘22 – Mar ‘23) to 32 deaths (Apr ‘23 – Mar ‘24).

Changes to the Bail Act in this instance focussed on:

Section 16B(1)(c1): Show cause requirement

Defendants facing charges of serious domestic violence offences that carry a sentence of 14 years or more imprisonment (e.g. causing grievous bodily harm with intent, kidnapping, choking or strangulation to make an intimate partner unconscious and incapable of resistance) will now be required to show cause. The onus is on the accused to show why they should not be in detention. This has also been extended to coercive control offences, which came into effect on July 1, 2024 and carry a maximum of 7 years imprisonment.

Section 18(1)(d1): consideration of historical offences for bail applicants of domestic violence offences

Amendments to section 18 now make it possible for the court to consider any historical offences of animal abuse or stalking, physical abuse or violence (such as strangulation or sexual assault) when considering bail.

Section 28B: Electronic monitoring

This section now makes electronic monitoring a mandatory bail condition for offenders that have had to show cause and have been granted bail. This is not necessary if it can be shown that there are sufficient reasons to show that it is not in the interests of justice for the offender to be monitored electronically. This section also stipulates that electronic monitoring is not a reason for detention to not be justified.

Section 40: Stay of release

‘Stays of release’ are now available to prosecutors for persons charged with serious domestic violence and coercive control offences. In legal terms, the word ‘stay’ means pause, meaning that accused persons are held in custody despite being awarded bail. In this instance, if a Magistrate grants bail to a defendant charged with show cause offences, prosecutors can still apply for the accused to remain in custody until a detention application is heard by the Supreme Court and a determination made.

Section 70A: Registrars must not make bail decisions

It is now a requirement of the Act that only Magistrates or Judges, not Registrars, can make bail decisions. This amendment was prompted by the death of Molly Ticehurst in April 2024, whose accused murderer was released on bail by a court Registrar presiding the bail application for serious domestic violence offences against Ticehurst. The offences included rape, stalking and intimidation.

Further Readings

Case Examples

Show cause, length of remand, conditional bail granted R v Toksoz [2015] NSWSC 1234

Show cause, family circumstances, flight risk, electronic monitoring R v Xi [2015] NSWSC 1575

Show cause, flight risk, bail granted R v Chen [2022] NSWSC 113