The Coroner’s Court

Inquests, Inquiries and Notable Cases

History of the NSW Coroner’s Court

The role of the coroner dates back to 1194 in England, where early coroners primarily handled administrative tasks, such as collecting taxes and maintaining the King’s records. In 1787, the Coroner’s Court became part of the legal system in New South Wales under Governor Phillip. Over time, its responsibilities expanded to include investigating deaths.

From 1861, the Coroner’s Court was also given the authority to conduct inquests into fires and explosions.

Legislation

The Coroner’s Act 2009 (NSW) (the Act) governs the operations of the NSW Coroner’s Court.

Under this legislation, the court is responsible for:

-

- Investigating certain deaths to determine the identity of the deceased, as well as the date, place, circumstances, and medical cause of death.

- Examining the cause and origin of fires and explosions.

Reportable Deaths and Fires

The NSW Coroner’s Court has jurisdiction to investigate a death if the deceased had a connection to NSW. According to the Act, this includes individuals who:

-

- Were ordinarily residents of NSW;

- Were in NSW at the time of death; or

- Were traveling to or from a location in NSW.

For fires or explosions, the court has jurisdiction only if the incident occurred within NSW.

Fact: Each year, NSW coroners investigate approximately 6,000 reportable deaths.

Role of the Coroner’s Court

The Australian legal system is adversarial, meaning two opposing parties present their arguments in court. However, the Coroner’s Court operates differently; its purpose is not to determine guilt but to investigate the cause of an event. The goal is to understand how deaths, fires, or explosions occurred and to help prevent similar incidents in the future.

The Coroner’s Court follows an inquisitorial process, meaning:

-

- Coroners, Deputy State Coroners, and the State Coroner do not rely solely on accusations or presented evidence. Instead, they actively investigate and gather information.

- There are no opposing sides; all parties work together to uncover the truth.

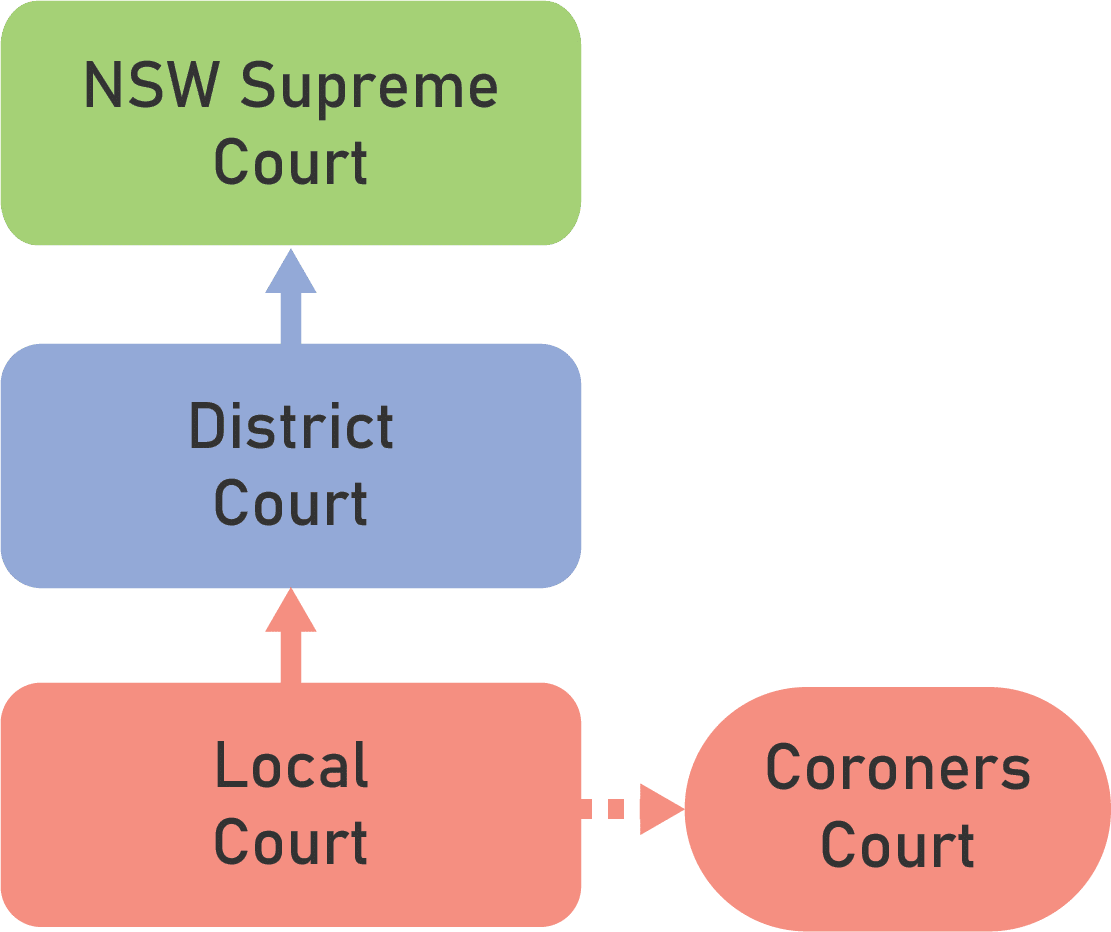

In New South Wales, the Coroner’s Court is a division of the Local Court and forms part of the NSW court hierarchy.

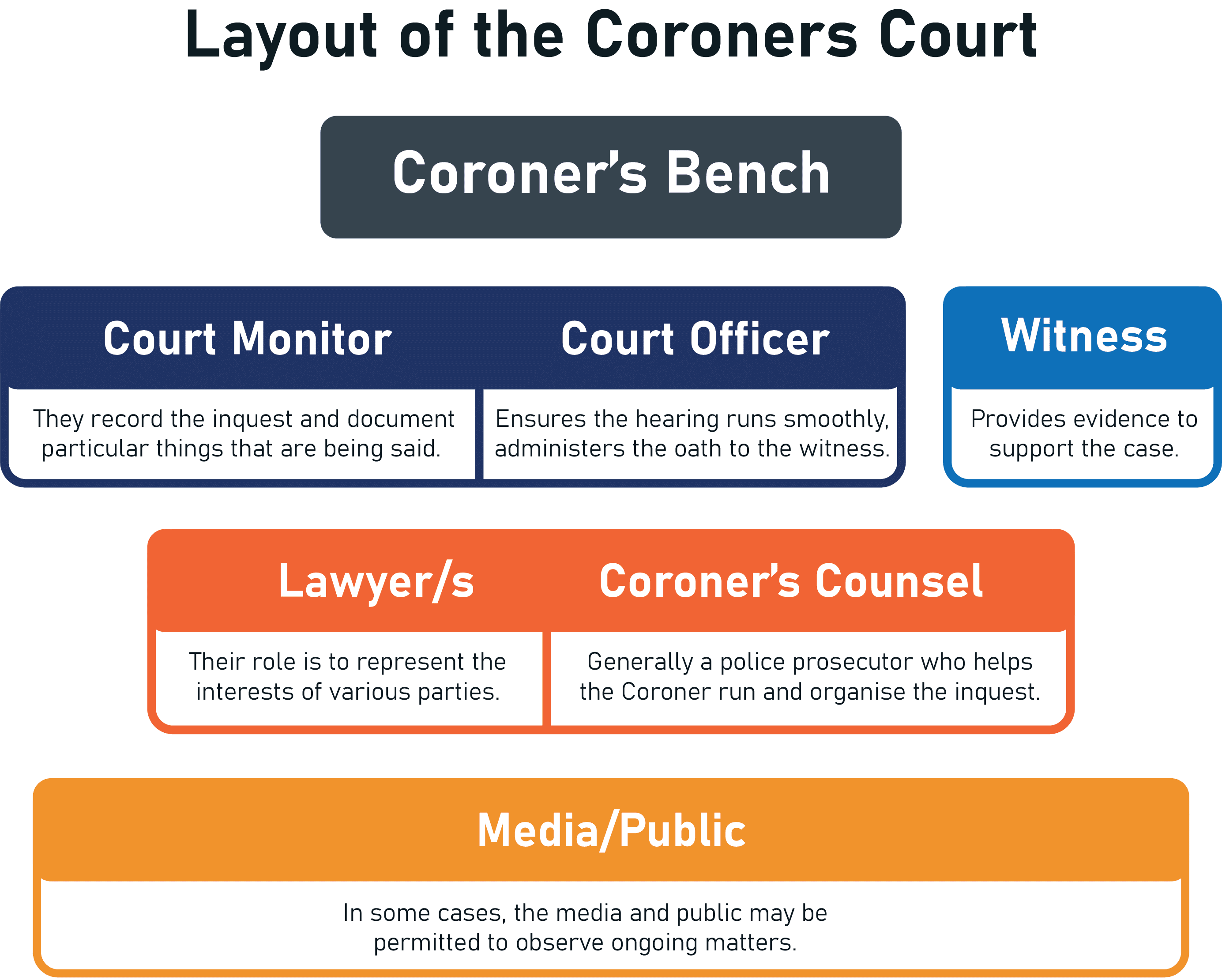

Key Figures in the Coroner’s Court

State Coroner, Deputy State Coroner, and Coroner

-

- As per Section 7(2) of the Act, the State Coroner and Deputy State Coroner(s) must be Magistrates of the Local Court and are responsible for presiding over proceedings.

- Section 12(2) allows the Attorney General to recommend other qualified Australian lawyers for appointment as Coroners by the Governor.

Purpose of a Coronial Inquest

During an inquest into a death, the coroner seeks to answer the following key questions:

-

- Who died?

- When and where did the person die?

- How did the person die?

- What happened and why?

In cases involving fires or explosions, the coroner investigates to determine their cause and origin. The coroner’s findings help improve public safety by identifying preventable risks and making recommendations to reduce future incidents.

Inquests and Inquiries

What is an Inquest?

An inquest is a court proceeding where the coroner examines evidence to establish:

-

- The identity of the deceased;

- The date, place, and circumstances of death; and

- The medical cause of death

An inquest may investigate a single death or multiple deaths. At its conclusion, the coroner will issue a formal finding. The diagram below outlines the process of a coronial inquest in NSW.

What is an Inquiry?

An inquiry is a court proceeding where the coroner investigates the cause and origin of a fire or explosion that resulted in property damage, but did not cause any deaths.

Jurisdiction

The Coroners Court is a division of the Local Court in NSW and sits in the NSW court hierarchy as follows (pictured right):

Fact: The average duration of an inquest or inquiry in NSW is 12 months.

Outcomes of Inquests and Inquiries

At the end of an inquest or inquiry, the coroner may issue:

-

- A finding of fact – A conclusion based on the available evidence.

- An open finding – A determination that a crime or death has occurred but without identifying a perpetrator or a specific cause.

Once a finding is made, the coroner may take the following actions:

-

- Making Recommendations to Government: The coroner can provide recommendations to government agencies aimed at improving public safety and preventing similar incidents.

- Referring a Matter to the DPP: Although the coroner cannot convict anyone of a crime, they may refer a case to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) if they believe a known individual has committed an indictable offence related to the death. In such cases, the coroner must suspend the inquest, and it is then up to the DPP to decide whether to pursue charges.

Review of Coronial Decisions

The review process for coronial decisions in NSW aligns with the appeals system in other courts, ensuring consistency and fairness. This review mechanism supports key rule of law principles, including transparency, impartiality, and judicial independence. It also serves as an important check on the powers and procedures of the Coroner’s Court.

If you have a sufficient interest in a death, fire, or explosion under investigation, you can request a review by writing to the NSW State Coroner. If a hearing has been waived, you may also ask the coroner for written reasons for the decision – an example of open justice.

A Coroner may reopen an investigation if new or fresh evidence emerges that makes it necessary or serves the interests of justice. This occurred in the inquest into the death of Azaria Chamberlain, as discussed below.

In NSW, the Supreme Court has the authority to order an inquest or inquiry if the coroner has decided not to hold one. The Court can also direct a fresh hearing if it is deemed necessary in the interests of justice.

The Coroner’s Court and the Rule of Law

How do coroner’s court hearings uphold the rule of law?

Equality Before the Law

The Coroner’s Court ensures that the law is applied equally and fairly to all individuals. It investigates any sudden, unexpected, or unexplained death, regardless of the person’s status, reinforcing the principle that justice is impartial.

Access to Justice

The Coroner’s Court provides a pathway for citizens to report unexplained deaths, fires, or explosions. If deemed necessary, an investigation is conducted, allowing individuals to seek answers and legal resolutions. This ensures that justice is accessible to all.

Transparency, Independence, and Impartiality

Inquests and inquiries in the Coroner’s Court are open to the public and the media, promoting transparency and accountability. Public access allows legal proceedings to be scrutinised, fostering trust and engagement in the legal system – both essential to upholding the rule of law.

Impact on the Presumption of Innocence

While the Coroner’s Court does not determine guilt, its findings can influence the presumption of innocence if a case is referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). Publicity surrounding coronial hearings may shape public and jury perceptions, potentially prejudicing an accused person’s right to a fair trial. Additionally, coronial proceedings do not adhere to the strict rules of evidence applied in other courts, further complicating this issue.

Fair and Timely Outcomes

The length of coronial inquiries in New South Wales varies, but on average, hearings take 12 months to complete. If a related criminal trial follows, the process can extend for years. These delays can impact the ability of affected parties to receive timely and fair resolutions.

How do they work?

Case Study 1: Fire Inquiry: NSW Bushfires Coronial Inquiry

The NSW Bushfires Coronial Inquiry commenced in August 2021 and is still currently before the NSW

Coroners Court. This inquiry is an investigation into the property damage and destruction arising from

the 2019-2020 NSW bushfire season. The inquiry has also opened a number of inquests into the deaths

arising from the fires during this time. The State Coroner is focussing on events particular to each

death, rather than a widespread investigation into the bushfires which has already been conducted by

the NSW Independent Bushfire Inquiry.

To give you an idea of this particular inquiry, we have canvassed the events of two different hearing days:

May 11 2021

- The inquiry opened inquests into the deaths of Andrew O’Dwyer and Geoffrey Keaton, both

volunteer firefighters, who died when a tree collapsed on their firetruck near Buxton on December 19 2019, causing their truck to veer off the road and down an embankment. - Witnesses, who were also in the fire truck at the time, were called to give evidence.

- Dash cam footage recovered from the fire truck was also admitted to the Coroners Court. It showed the tree crashing directly onto the fire truck.

- There was no evidence that could establish that Geoffrey Keaton, the driver, had braked after the

tree fell down. - It is likely that Geoffrey Keaton had no control of the fire truck once the tree hit the top of the truck.

March 21 2022

- The inquiry opened an investigation into the Bills Crossing Crowdy Bay Fire which started on 26 October 2019.

- The fire burned for 9 weeks and covered 13,000 hectares. 84% of the Crowdy Bay National Park was impacted by the fire. 6 properties were damaged or destroyed by the fire.

- The fire caused 1 fatality.

- Mark Fullgar, from the RFS fire investigation and arson intelligence who as tasked with investigating the fire, was called to give evidence at the Coroners Court. He gave evidence that lightning could be the only cause of the fire, due to the inability of anyone to physically get in to the site due to its remote location.

As mentioned before, the NSW Independent Bushfire Inquiry was conducted in January 2020 (before the NSW Bushfires Coronial Inquiry) and was an independent expert inquiry into the 2019-20 bushfire season. The aim of this Independent inquiry was to provide recommendations to NSW ahead of the next bushfire season. It outlined 76 recommendations, which can be read here in the final report (https://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/assets/dpc-nswgov-au/publications/NSW-Bushfire-Inquiry1630/Final-Report-of-the-NSW-BushfireInquiry.pdf). The recommendations are aimed at improving bushfire preparedness and response.

Case 2: Disappearance Inquest: Inquest into the Disappearance of Theo Hayez

An inquest into the disappearance of Belgian backpacker, Theo Hayez, began in November 2021 and continued through to December 2021 at the Byron Bay Coroner’s Court. 18 year old Theo was last seen at about 11pm on 31 May 2019 walking away from a nightclub in Byron Bay. His body has never been found.

The inquest heard that Theo’s mobile data, uncovered by his family, shows he searched on Google Maps for directions back to his hostel, but then walked towards the Cape Byron Lighthouse in the opposite direction. Analysis of Theo’s phone data suggests that he tried to scale the steep headland below the Lighthouse that night. This data also indicates that Theo never reached the Lighthouse.

The Officer in charge of the case gave evidence at the inquest that Theo’s bank and social media accounts have not been used since the day of his disappearance, and he therefore believes Theo is deceased.

The only piece of evidence found was Theo’s grey cap he had been wearing on the night of his disappearance on July 7 2019. State Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan ordered another search of the northern end of Tallows beach in October 2021, but no new evidence was uncovered. The inquest has heard that there is no evidence of foul play in Theo’s disappearance. A number of theories have emerged:

- Theo was disoriented due to intoxication.

- Theo was trying to find a beach party on the beach below the Lighthouse with an unidentified person. Theo was seeking to visit the famous Lighthouse.

The current police theory is that Theo scaled the cliffs near the Lighthouse, then fell and was swept out to sea.

The findings of the inquest are set to be handed down on 21 October 2022.

Case 3: Death Inquest and Referral to the DPP: Inquest into the Death of Parwinder Kaur

On December 2013, Parwinder Kaur died as a result of receiving burns to almost 90% of her body. She was seen by neighbours running down the driveway of her Sydney home engulfed in flames. A police investigation took place following the December 13 incident, but it was left at a loose end. Following widespread media attention, the case was referred to the Coroner.

The Coronial inquest into Parwinder’s death began on 28 September 2015 at the NSW Coroners Court. About a month later, on 27 November 2015, the NSW Coroners Court formed the opinion that:

“the evidence was capable of satisfying a jury beyond reasonable doubt that a known person [had] committed an indictable offence, that there was a reasonable prospect that a jury would convict the known person of the indictable offence, and that the indictable offence would raise the issue of whether the known person caused the death with which the inquest or inquiry [was] concerned.”

On 1 November 2017, Parwinder’s husband, Kulwinder Singh, was charged with his wife’s murder. Kulwinder’s first trial began on 18 October 2019 resulted in a hung jury. Following the second trial on 29 March 2021, the jury found Kulwinder innocent.

To read more about the Case click here.

Case 4: Death Inquest and Recommendations: Inquest into the Death of Danukul Mokmool

An inquest into the death of Danukul Mokmool began in May 2019 and concluded in June 2019. On 26 July 2017, a number of triple 0 calls were received claiming that a man, later identified as Mokmool, was wielding scissors and threatening a shopkeeper. Four police officers ran to the scene where one officer attempted to used pepper spray on Mokmool, but it had no effect. Mokmool ran at Senior Constable Tse wielding the scissors. Senior Constable Tse and Senior Constable Jakob Harrison opened fire and shot four times. Mokmool died as a result of a gunshot wound to the head.

The findings, handed down on 5 August 2019, by Deputy State Coroner Elaine Truscott were that:

“Danukul Mokmool died on 26 July 2017, at Central Railway Station, Eddy Avenue, Sydney, of a gunshot

wound to the head, as a result of a police operation. He was experiencing a psychotic episode and was shot by police officers in circumstances where he ran at police with scissors in his hands…”

She then made the following recommendations to the Commission of Police NSW in order to improve outcomes in the future:

“…That consideration be given to amending the applicable Standard Operating Procedures so that uniformed officers performing frontline duties are required to carry a Taser absent good reason not to.”

Case Study 5: Azaria Chamberlain

One of Australia’s most high-profile cases, the death of Azaria Chamberlain on 17 August 1980 at Uluru in Australia’s Northern Territory, also known as the ‘dingo’s got my baby‘ case, led to four separate coronial inquests.

Inquest 1: 16 December 1980

It was put forward in evidence that the damage caused to Azaria’s clothing was inconsistent with what could be caused by a dingo. The Coroner, Barritt J, concluded that neither of Azaria’s parents were “in any degree whatsoever responsible for her death.” However, Barritt J made an open finding, stating “the body of Azaria was taken from the possession of the dingo and disposed of by an unknown method, or by a person or persons name unknown.”

Inquest 2: 14 December 1981

The second inquest into Azaria’s death came about when the Attorney General of the NT, Chief Minister Everingham, filed a motion to quash the findings of the first inquest based on newly discovered evidence: quantities of blood in the Chamberlain’s car. It was put forward at the inquest that Lindy Chamberlain, Azaria’s mother, took Azaria from the campsite and murdered her in the family’s car with a sharp instrument.

Biologist Joy Kuhl gave evidence at the inquest that she found fetal blood beneath the passenger seat of the car. Dingo expert James Cameron was also called to give evidence. He found that the tear in Azaria’s clothing could not have come from a dingo, stating it was “more consistent with scissors.”

During the inquest, the Coroner formed the belief that Lindy and Michael (Azaria’s father) Chamberlain had committed the murder of their daughter. The matter was therefore referred to the DPP and the second inquest was never been completed. At the subsequent trial, Lindy was charged with the murder of Azaria and Michael was charged as an accessory after the fact

Inquest 3: December 1995

The discovery of Azaria’s matinee jacket in an area with several dingo lairs in 1986 led to Lindy’s release from prison, after the NT Court of Criminal Appeals unanimously overturned Lindy’s and Michael’s convictions. In December 1995, a third inquest into Azaria’s death resulted in an open finding. The Coroner, John Lowndes SM, found that the evidence adduced did not enable him to determine the cause and manner of Azaria’s death.

Inquest 4: 12 June 2012

The fourth inquest into Azaria’s death was held in June 2012 before Coroner Elizabeth Morris SM. The purpose of this inquest was to determine whether there was sufficient evidence to adduce a cause of death of Azaria. The Coroner found “the cause of [Azaria’s] death was as the result of being attacked by a dingo.”