The Drug Courts

Specialist Courts

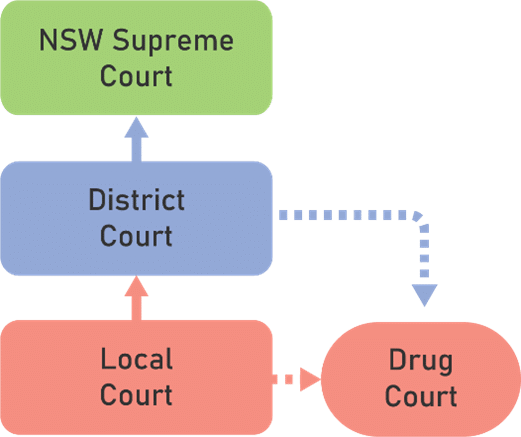

Along with the Coroners Court, the Youth Koori Court and the Children’s Court, the Drug Court is a specialist court that sits at the Local Court level in the NSW court hierarchy. For more information on court hierarchies, view our resources here.

What are Drug Courts?

Drug Courts are a form of therapeutic justice. This means that their focus is on improving the wellbeing of offenders with a drug dependency by addressing their underlying drug problem, which in many cases is the cause of criminal behaviour and recidivism.

Drug Courts are also a diversionary program, which is a type of alternative sentencing program designed to divert disadvantaged individuals, who have typically committed non-violent offences, away from the traditional criminal justice system. This is because conventional forms of punishment, such as fines and imprisonment, are often not effective means of rehabilitating and reforming offenders with issues of drug dependency. Imprisonment also deprives offenders of the social and medical help they needed, making recovery and progress virtually impossible.

The world’s first Drug Court was established in Florida, USA, in 1989, with the first Drug Court in Australia created in NSW in 1999. Drug Courts now operate in each state and territory jurisdiction in Australia, excluding Tasmania and the Northern Territory. In some locations, such as the ACT and Victoria, diversionary programs are also available to defendants that have alcohol dependency issues.

Figure 1 The Drug Court in the NSW Court Hierarchy

Case Study: The NSW Drug Court

The NSW Drug Court is a legislated court, meaning that it is receives regulated by its own legislation, policies, and past decisions (precedent).

As a legislated court, the Drug Court receives direct funding from the Attorney General has the discretion of choosing how to allocate the funding it receives from the Attorney General’s Department. It operates at the Local Court level of the hierarchy.

The statute laws governing the NSW Drug Court are the Drug Court Act 1998 (NSW), which outlines the requirements for an individual’s referral to the Drug Court, and the Drug Court Regulation 2020 (NSW), which provides more specific rules on Drug Court procedures.

A prominent feature of Drug Courts are their approach to community-based rehabilitation. Often collaborating with community service and social support agencies, their aim is to help re-integrate drug dependent offenders back into society.

The Drug Courts’ Role?

The Drug Courts attempt to work with offenders to address the underlying cycles of drug dependency that are often a source of criminal offences, such as assaults, theft, domestic violence and traffic offences.

The three main roles of the Drug Courts are:

- To reduce the drug dependency of eligible persons,

- To promote the re-integration of such drug dependent persons into the community and

- To reduce the need for such drug dependent persons to resort to criminal activity to support their drug dependencies.

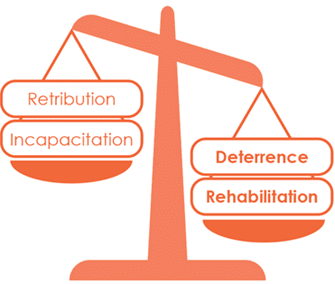

The purposes of punishment that the Drug Court Program supports have different weights compared to those of imprisonment. (Visit the Australian Law Reform Committee website to learn about the purposes of punishment in detail.)

Fig. 2: An illustration depicting the purposes of punishment that the Drug Courts aim to achieve.

Operation of the NSW Drug Court

Eligibility and Referral

As mentioned before, each State Drug Court varies slightly in procedure. To be eligible for the Drug Court program in NSW, a person must:

- be charged with an eligible offence

- be 18 years of age or over

- have pleaded guilty to the offence

- is able and willing to participate (voluntary participation)

- be highly likely to be sentenced with full-time imprisonment

- be referred by a Local/District Court

- be dependent on the use of illicit drugs as recognised by the Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 (NSW)

Certain offences involving violent or sexual conduct will automatically disqualify the offender from eligibility.

Process

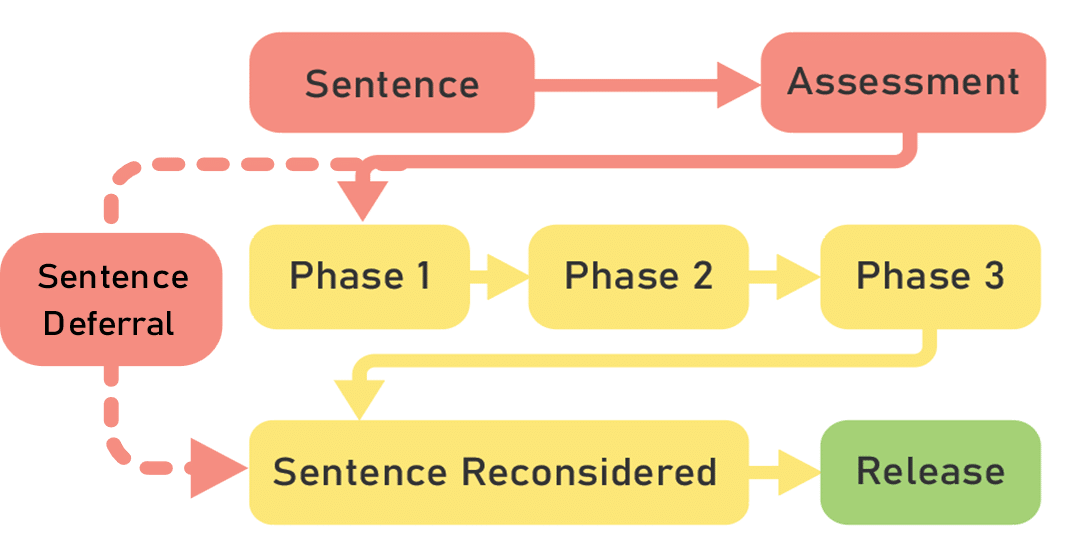

After an offender has been sentenced for their offences, they are temporarily held in a correctional facility as their individually tailored treatment plan is developed. This involves the collaboration of medical staff, doctors, and psychiatrists to assess the offender’s unique circumstances and risks.

To increase the chances of successful rehabilitation, the program is structured into three phases.

Phase 1: Initiation

After their assessment, the offender moves into Phase 1 (min. 3 months). During this phase, participants must:

- gradually reduce drug use

- take steps to stabilise their physical and mental health

- commence treatment for drug dependency

- cease criminal activity

- undergo supervised urine drug testing at least three times per week

- report back to the court up to twice per week

Figure 3: The process of the Drug Court program

Phase 2: Consolidation

In Phase 2 (min. 4 months), participants must:

- remain free of and crime,

- maintain good health,

- stabilise domestic and social environments

- develop job and life skills (typically through training courses provided by social support services)

- undergo supervised urine drug testing twice per week

- report to the court once per fortnight

Phase 3: Reintegration

In Phase 3 (min. 5 months), participants must:

- gain accommodation

- be employed (if not engaged in full-time childcare) or in training to be employment ready

- be financially responsible

- undergo drug testing twice per week

- report to the court once per month.

If the participant successfully completes all three phases, they will have a graduation ceremony upon completion.

How many offenders participate in the Drug Court Program in NSW?

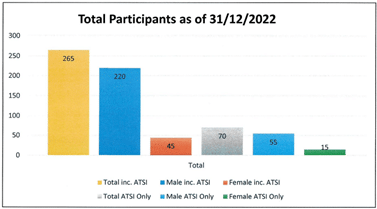

In its Annual Review of 2022, the Drug Court reported that most of the referrals to the Drug Court are made by the District Court. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of participants as at the end of 2022.

It is also noted that the covid impact on the Drug Court was significant due to the reduced number of committal matters being heard by the District Court, reducing the ability of offenders in remand to be able to meet all criteria. This meant that the Compulsory Drug Treatment Correctional Centre (CDTCC) was operating under capacity for most of 2021 and 2022, with numbers starting to increase at the end of 2022.

Get out of Jail Free?

The Drug Court Program does not free offenders without consequence. Most commonly, offenders will still face their sentence after the conclusion of the program, though their initial sentence will be reconsidered based on their participation in the program (s.12 Drug Court Act 1998 (NSW)).

Additional mandatory considerations include whether any further sanctions have been imposed on the drug offender during the program, and whether the offender had been held in custody, either under their sentence or during the course of their program.

For example, if their initial sentence was relatively minor and the offender had displayed excellent signs of rehabilitation, their sentence may be greatly reduced (i.e. they may be sentenced to Community Service work instead of a custodial sentence, or their sentence may be dismissed entirely).

However, if an offender who had initially been sentenced to prison does not comply with the program, they will likely serve their prison sentence the conclusion of their program.

Does it work?

In its two decades of operation, has the NSW Drug Courts Program yielded real, substantial results for society? How can this be measured?

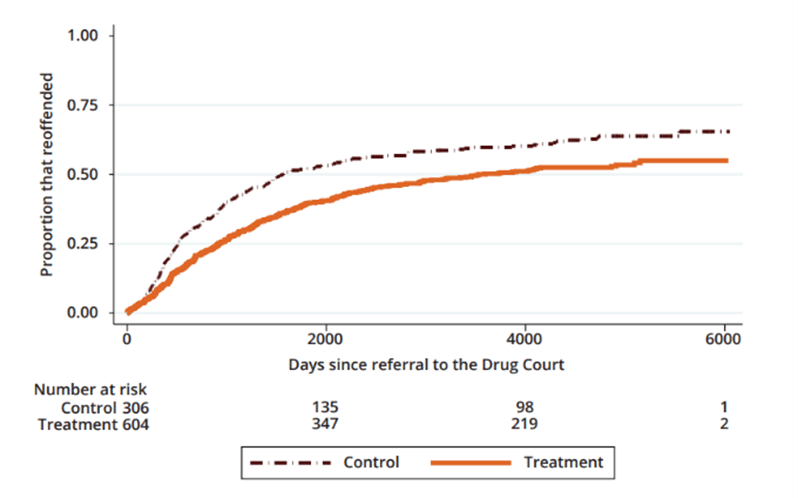

A 2020 BOCSAR (Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research) study on the effect of the Drug Court program on recidivism measured the long-term differences between a large group of offenders who underwent the program (the treatment group) compared to offenders who did not (the control group).

The study found that the treatment group participants who successfully completed the program recorded a 17% lower reconviction rate, and those who did reoffend took 22% longer to do so compared with reoffenders in the control group.

It should be noted that the results of the treatment group were taken from those who had successfully completed the program, which constituted only 40% of the total treatment group. The other 60% had their programs terminated.

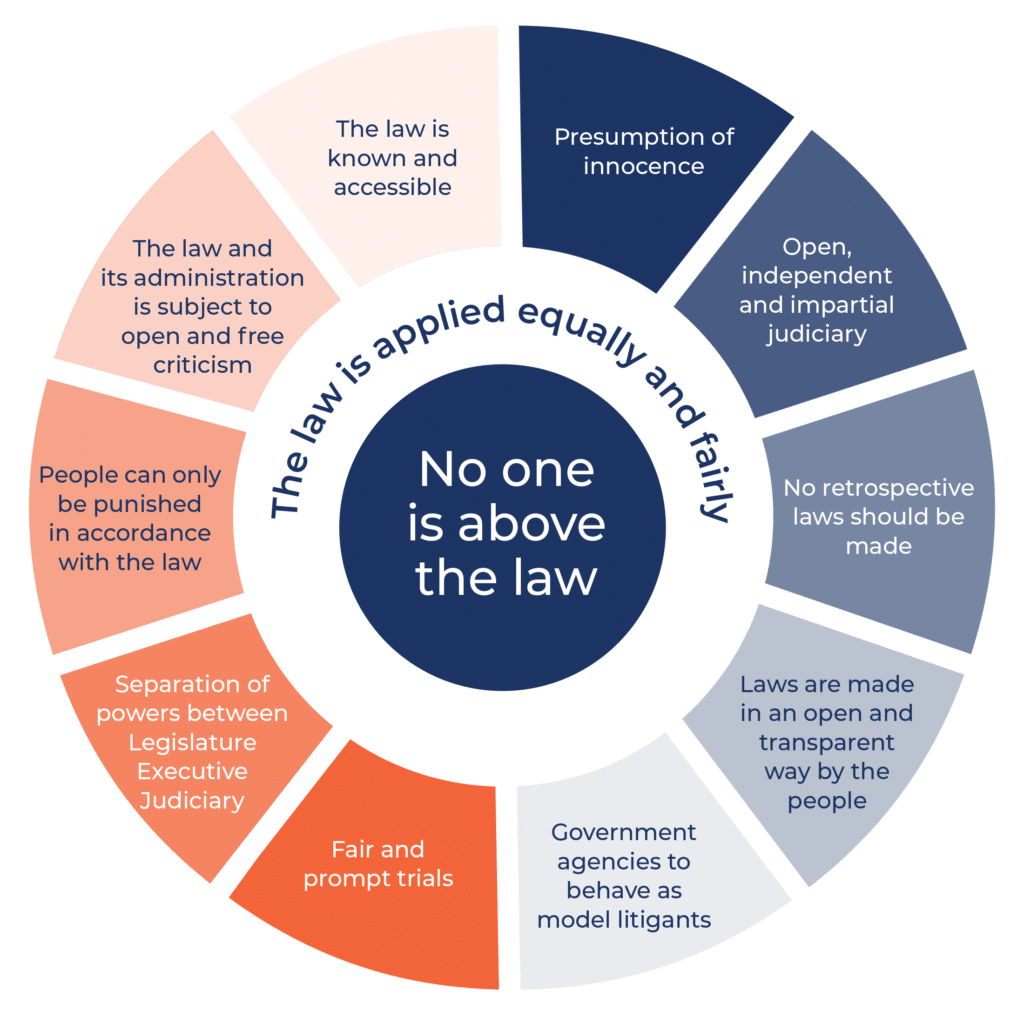

Application to the Rule of Law Principles

Access to Justice

The various Drug Courts of Australia provide access to justice for drug dependent individuals, who often reside in some of the most disadvantaged communities in the nation.

People living in these communities regularly face issues such as poverty, unemployment and cycles of addiction, which often generate even greater concentrations of criminal activity compared to other areas. Alternative avenues that divert from traditional punitive measures can provide offenders with the opportunity to improve their outcomes.

Individuals who are affected by drug use have a higher tendency to suffer from socioeconomic disadvantage and mental illness. As a result, the courts often provide free Legal Aid so that the offender can have a legal guide and representation in court and offenders with lower income are not forced to face the difficulties of representing themselves in court. Pro bono workers (unpaid volunteer workers) from community agencies often assist with ongoing case management.

Fair and Just Outcomes

The Drug Court offers an alternative avenue of justice through which the offender can receive rehabilitation, providing them an opportunity to rehabilitate and become more productive members of society. This results in a more equitable outcome for the many offenders who have been trapped in a cycle of substance abuse, perhaps due to generational cycles of addiction or a lack of education about the effects of drugs.

However, weighing up the fairness of these measures involves considering all parties involved, including the victims of drug-related crimes, who may desire retribution for the harm or loss they have experienced. The Drug Court program balances these priorities by still enforcing the offenders’ sentences.

Drug Court Case Examples

R v Joshua Luke CAGE [2014] NSWDRGC 1

R v Cage illustrates how the law addresses offenders who breach the terms of their Drug Court rehabilitation program by reoffending.

Mr Cage was initially sentenced in 2010 with respect to 31 offences, but this sentence was ultimately deferred when he was referred to the Drug Courts and was admitted into the Drug Court program.

During his program however, Mr Cage engaged in a spree of criminal activity, most notably involving breaking and entering, stealing, driving while disqualified and breaking the conditions of his program by relapsing into drug use.

Mr Cage’s Drug Court program was terminated soon after, and while on trial, it was held that his new sentence for the offences ‘cannot be even partially cumulative with the 2010 sentence’ and must be served on top of his previous sentence, pursuant to s 58 of the Drug Court Act. His final sentence was 4 years and 3 months of imprisonment.

R v Miller; R v Omar [2021] NSWDRGC 1

Can the Drug Court sentence an offender for a federal crime and provide that offender with a Drug Court program?

In July of 2020, Mr Miller and Mr Omar had pleaded guilty to conspiring to commit social security fraud, which is a federal offence (a crime against Commonwealth law). In the Sydney District Court, where their matters were heard, Miller and Omar had submitted medical records of their drug dependency. Satisfied that the two men ‘appeared to’ be eligible for the Drug Court Program, His Honour Acting Judge Armitage referred both matters to the Drug Court of New South Wales pursuant to s6 of the Drug Court Act 1998 No 150 [NSW].

However, when the matter was heard in the Drug Court in March 2021, it was held that the Drug Court did not have the jurisdiction to sentence Federal offences. This was decided as s 7A(3) of the Drug Court Act 1998 No 150 [NSW] requires the Drug Court to sentence the person in accordance with the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 [NSW], which denies the Drug Court the jurisdiction to sentence federal matters,

Other Jurisdictions

Because each state drug court is governed by its own legislative frameworks, they vary in their procedures, however the aims remain the same.

Queensland

The Queensland Drug and Alcohol Court (QDAC), oversees drug and alcohol dependency rehabilitation programs. The legislative basis for the QDAC appears in Part 8A of the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld) and incorporates the principles of the Drug Court program into the sentencing legislation for Queensland. Guidelines for the making of Drug and Alcohol Treatment Orders (Treatment Orders) are found in s151C of the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld).

Its Drug and Alcohol Treatment Orders can last up to two years, as opposed to the NSW Program which has a maximum length of one year.

South Australia

South Australia’s Treatment Intervention Court (formerly called the Drug Court) operates as a subdivision of the Adelaide Magistrate Court. Similar to NSW, the program has 3 phases undertaken over a 12-month period, with a demerit point system in place for failure to comply with conditions of the program.

However, a shorter, 6-month program is available for drug dependent offenders who aren’t facing imprisonment. In this version, home detention is not compulsory, however, residential accommodation is not available to participants as in the 12 month program.

Victoria

The Victorian Drug Court is established under s 4A of the Magistrates Court Act 1989 (Vic). The program involves a Drug and Alcohol Treatment Order (DATO), which includes a custodial sentence. Offenders are required to serve some amount of their imprisonment sentence under strict conditions in the community (as opposed to jail), undergo treatment and are supervised by a Drug Court Magistrate.

Western Australia

In Western Australia, the Perth Drug Court was established in December 2000 and operates within the Perth Magistrates Court. Offenders are placed into one of three Drug Court programs can vary based on the seriousness of their offences.

At the Magistrates court level, similar to NSW and SA, the Pre-Sentence Order (PSO) program has 3 phases generally completed over a 12-month period. It imposes strict bail conditions on participants.

The program enables the court to delay sentencing for up to 2 years while the offender participates. Compliance with the program may make it possible for the court to not impose a sentence after the completion of the PSO.

Offenders facing serious charges through the District and Supreme Courts (and therefore are not eligible for the PSO) may also be eligible for the Conditional Drug Court Regime (DCR) while they are on conditional bail after entering a plea into their matter. Offenders are referred by the presiding judge or justice and if deemed eligible and approved, they will be case managed by a magistrate.

There is also a Drug Court operating in the Perth Children’s Court.

ACT

The Drug and Alcohol Sentencing List (DASL) was introduced in 2019 and operates in the Supreme Court of the ACT. A 2022 report evaluating the processes and outcomes of the DASL conducted by the Australian National University estimated that the program had saved the ACT Government over $14 million in jail costs since its commencement in 2019.

In addition, it states that none of the graduates had appeared before court since their graduations, and of those who did not complete the program, offending rates were reduced.

Tasmania

Tasmania does not have dedicated a Drug Court, but has a sentencing option through the Magistrates Court for drug-dependant offenders. The Court Mandated Diversion Program operates similarly to programs in NSW and SA.

Northern Territory

There is currently no specialist Drug Court in operation in the Northern Territory, however, the Local Court operates a Specialist Jurisdiction List – Treatment Orders under the section 36 (2) of the Volatile Substance Abuse Prevention Act 2005 (NT). Applications for participation must be approved by the Chief Judge.

Activity

Considering that the Drug Court Program is quite expensive for the government to run, and the process of rehabilitation creates delay within court proceedings, do you think the Drug Court program is an effective method of restorative justice? What are its pros and cons?

In your answer, consider the data gathered by NSW BOCSAR in this report (the findings have been summarised in the previous section Does it Work?) as well as any case studies you can find.