Use of Evidence

The use of evidence in the Criminal Trial Process

In criminal proceedings, evidence is needed to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt and establish a verdict of guilty. Evidence can be classified into one of three categories: oral, documentary and other (or real) evidence, and the gathering and use of evidence is strictly regulated and governed by the relevant legislation in each state. This is to protect fairness during the trial and in sentencing considerations, and to protect against false imprisonment of accused persons.

Mason P, Wood CJ and Sully J in their judgement in the Skaf Brothers Appeal said:

[274] … In a criminal trial, guilt must be established beyond reasonable doubt based upon admissible evidence. The rules of evidence are the sieve through which information must pass before the jury is required or entitled to consider it. Parties cannot rely upon information that is not proved according to these rules. This is no mere technicality. The rules embody significant policies designed to achieve fairness and efficiency.

R v SKAF and Another(2004) 60 NSWLR 86

What is evidence?

“Evidence, in law is any of the material items or assertions of fact that may be submitted to a competent tribunal as a means of ascertaining the truth of any alleged matter of fact under investigation before it”

– Brittanica

The concept of due process involves following established rules and procedures, including the rules of evidence, in legal proceedings to ensure a fair trial. The concept of due process originates from clauses 39 and 40 of the Magna Carta:

(39) No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land

(40) To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.

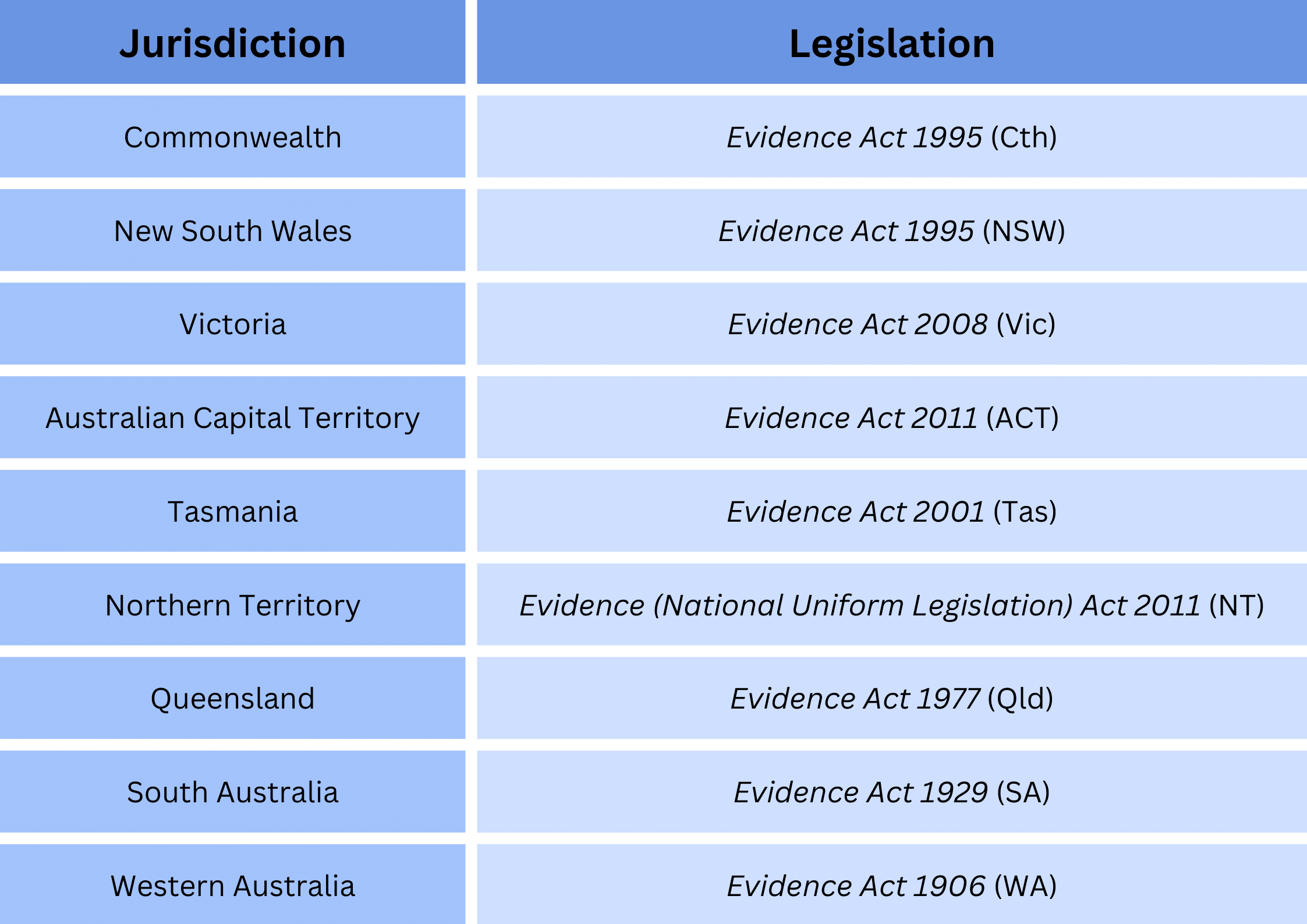

Legislation governing evidence

The use and admissibility of evidence in the criminal trial process is governed by legislation, which differs between States and Territories. The table to the right names all the in-force evidence acts in Australia.

Question:

Consider the age of the legislation in your state and how evidence gathering, handling, type and use has changed over time. Outline the process that legislators would use to address these changes.

Case study: Evidence gathering and use in NSW

Gathering Evidence in the criminal investigation process

NSW Police are charged with investigating and gathering all available evidence that might be used during a trial to prosecute an accused person. Police are given special powers to carry out their duties, the majority of which are contained in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) (“LEPRA”).

Specific to evidence gathering, s95(1)(g) of the LEPRA gives police the powers to “perform any necessary investigation, including, for example, search the crime scene and inspect anything in it to obtain evidence of the commission of an offence” and s95(1)(m) gives police the power to “seize and detain all or part of a thing that might provide evidence of the commission of an offence”. Section 95(2)(a)-(b) further confers on police the power to remove objects from crime scenes when found or guard the item in place as part of the seize and detain powers.

The use of evidence in the criminal trial process

The Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) is the legislation that governs the use of evidence in legal proceedings in New South Wales.

Once evidence is gathered, it is then used to determine whether a prosecution can proceed. Police will collate the evidence into a ‘brief of evidence’. The brief can comprise of documents, including statements, exhibits including CCTV footage or photos, and the results of any forensic tests.

The brief will be sent for review to either:

- For summary offences and indictable offences that can be heard summarily: the NSW Police Prosecutor’s Office of the court the matter will be heard in; or

- For more complicated or serious indictable offences that will proceed to the District or Supreme Courts: The NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP).

The evidence is carefully reviewed and assessed by the relevant body, and a decision is made on whether there is enough evidence to proceed to prosecution. This decision is based partly on the strength of the admissible evidence and the likelihood of a conviction given the evidence. Decision on whether to prosecute is made by the police prosecutor or the ODPP.

If a decision is made to commence legal proceedings, strict rules outlined in the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) govern what evidence is able to be used (admissible) and how that evidence can be used in court.

Before the start of a trial, both the Crown and the Defence put forward the evidence they intend to rely on during the criminal trial process to support their case. The Crown has a duty to make full and early disclosure of the prosecution case and evidence, which means the Crown must hand over all material relevant or possible relevant to the case to the Defence. The Defence does not have the same duty as the Crown, but does have a duty to disclose evidence, but only for particular types of evidence, such as alibi evidence and expert evidence

Any and all evidence introduced into court is able to be tested by the other party. This means both parties have the opportunity to question the validity or admissibility of the evidence being presented the court by the opposing party.

Evidence and the adjudicators of fact – jury or judge?

In jury trials, the jury makes a decision on the facts after having been presented with all of the admissible evidence from both parties. The jury’s ultimate verdict must be based solely on the evidence and in accordance with the law, as explained by the judge to the jury when they give the jury their directions. The judge also can give the jury directions and cautions about the evidence presented.

When one party challenges the validity of a piece of evidence, for example, if there is a question as to whether an admission of guilt made by an accused person was made voluntarily or not, or whether there js a question as to whether evidence was legally obtained by police, a voir dire (‘to speak the truth’) may be held. In a voir dire, evidence is examined without a jury to determine its admissibility or determine whether it should be excluded. If evidence is found to be inadmissible in a voir dire, it cannot be introduced in the actual trial. The judge will apply the rules in the Evidence Act and their discretion to assess the evidence and determine whether it is admissible and can be used in the case presented to the court. Findings made on voir dire cannot be reported during the trial but are usually made public by the courts after the conclusion of the trial.

In judge-alone trials or local court hearings, the magistrate or judge must determine the admissibility of evidence before actually ‘hearing’ it or accepting it as evidence that can support a charge.

Direct v Circumstantial Evidence

Direct evidence proves a fact directly, such as testimony given by immediate witnesses to an act, or CCTV footage showing an act.

Circumstantial evidence “is evidence of circumstances which can be relied upon not as proving a fact directly but instead as pointing to its existence.” (Queensland Courts, 2017, no.48.1)

According to the Judicial Commission of NSW (2022), convictions based on circumstantial evidence can occur where “all of the evidence leads to an unavoidable conclusion that the Crown has established the guilt of the accused”.

Some cases where circumstantial evidence was used include: Chris Dawson, Keli Lane and Bayden Clay.

Types of Evidence

1. Oral Evidence (Witnesses) (Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) Part 2.1)

A witness is someone who has seen something or has knowledge about a fact relevant to the matter before the court. The court may issue a subpoena (a type of court order) that orders a person to attend court at a certain time and place to give evidence. Witnesses can be called by either the prosecution or the defence, and each party has the opportunity to examine the witness. Failing to follow a subpoena could result in a finding of contempt of court. There are three stages to a witness testifying, and the nature of the questioning of the witness is determined by which party has called the witness. These stages are: Examination-in-Chief, Cross-Examination, and Re-Examination.

Process of questioning witnesses in court

Examination-in-Chief

The questioning of a witness by the party who called them to give evidence (the summoning party)

i.e. a prosecution witness will be examined-in-chief by the prosecution

The witness cannot be asked leading questions during an examination-in-chief

Cross-Examination

The questioning of a witness by the opposing party. This gives the opposing party an opportunity to test the witness’s testimony by testing the accuracy and objectivity of the evidence

i.e. the cross-examination of a prosecution witness will be conducted by the defence.

The witness can be asked leading questions during an cross-examination.

Re-Examination

Used by the summoning party to clarify witness evidence where an ambiguity has arisen out of the cross-examination.

i.e. a prosecution witness will be re-examined by the prosecution.

Other questions cannot be introduced in re-examination unless the court allows it.

Questions cannot be leading

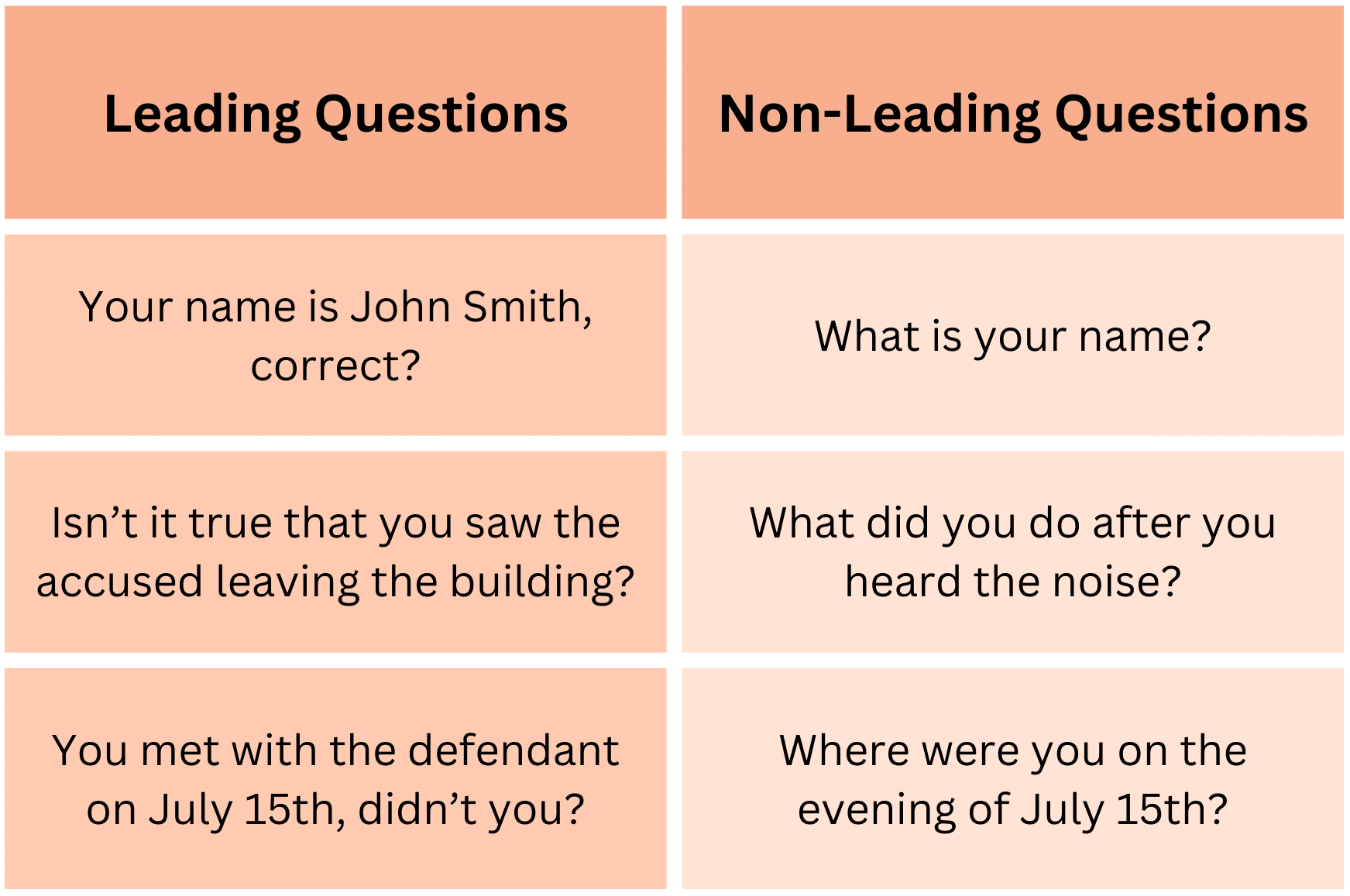

Leading questions are questions that give a prompt that will encourage the answer that is wanted. These questions are worded can lead a witness to not provide an answer that is truly reflective of their experience, but rather provides an answer that fits with the questioning parties’ interests. Leading questions have been shown to reduce the accuracy of witness accounts.

Non-leading questions are open questions that allow the witness to give their account as they recall it without having an answer presented to them in the question.

Does the accused have to give evidence?

The right to silence is based on the principle of the presumption of innocence, as it is for the prosecution to prove the guilt of the accused. An accused is not obliged to answer questions put to them by police officers nor to testify in their own defence at trial. Section 89 of the Evidence Act protects the accused from assumptions of guilt being made if they choose to remain silent, while s20 of the Act dictates that a trial judge or prosecutor cannot make an adverse comment or inference of guilt if the accused exercises their right to silence.

For example, in her murder trial, Keli Lane did not give any evidence.

2. Documents (Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) Part 2.2)

The Dictionary (Part 1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) defines ‘document’ to mean “any record of information and includes—

- anything on which there is writing or

- anything on which there are marks, figures, symbols or perforations having a meaning for persons qualified to interpret them, or

- anything from which sounds, images or writings can be reproduced with or without the aid of anything else, or

- a map, plan, drawing or photograph.

3. Other Evidence (or Real Evidence) (Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) Part 2.3)

Other evidence differs from oral testimony and documents; the production of it requires the court to reach conclusions on the basis of its own perception and not that of witnesses.

Material objects, such as a knife or a piece of clothing, may be produced to the judge and jury to enable them to form their own opinion on the matter.

The Rules of Evidence

Rules of evidence regulate the way in which criminal trials are conducted. They also make the conduct of a criminal trial predictable as they give consistency to the use of evidence across cases. The right to procedural fairness ensures that all parties will be given a reasonable opportunity to present their case.

Determining admissibility

The rules of evidence, which are applied in all courts across Australia, serve multiple functions, including:

- regulate the material that the court may consider whilst determining the facts of a case;

- how that material is to be presented in the court; and

- setting out how the court decides the facts of a case based on the evidence.

‘Admissible’ evidence is any document, testimony, or tangible (physical) evidence used in a court of law that goes towards helping to prove or establish the facts in issue in a case. A fact in issue is a fact that fundamentally affects the court proceedings.

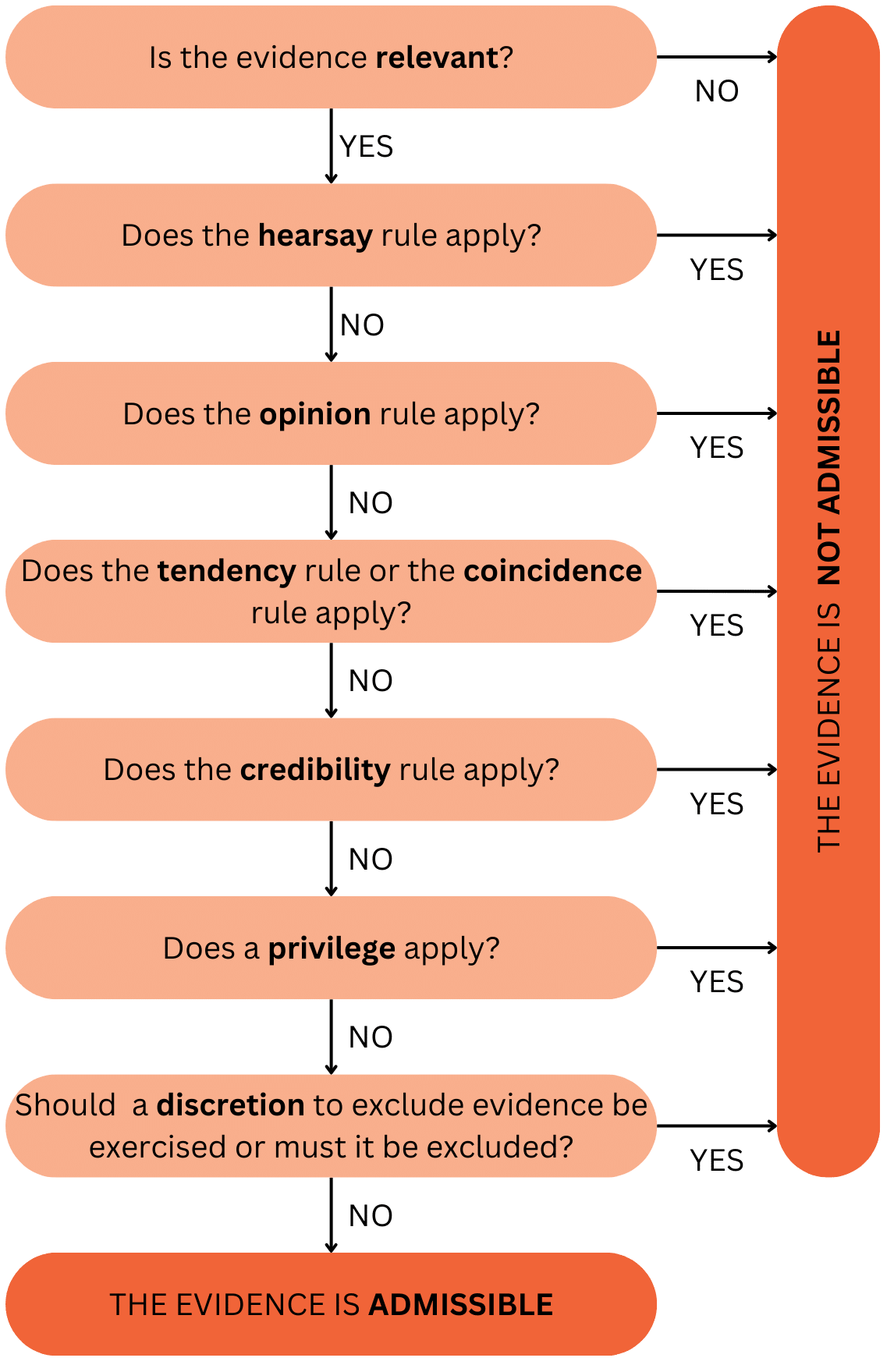

For evidence to be admissible in court, it must:

- pass through the thresholds outlined in the Evidence Act, as shown in the flowchart below, and

- must have been legally obtained by investigating police.

Adopted from the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) Chapter 3

Note: this is not an extensive list of the thresholds of admissibility, there are further thresholds outlined in the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW)

Relevance

The most important rule governing the admissibility of evidence is that it must be ‘relevant’ to a fact in issue. S55 of the Act states:

‘the evidence that is relevant in a proceeding is evidence that, if it were accepted, could rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue in the proceeding.’

This means that evidence is considered relevant if it could reasonably influence the judge’s or jury’s opinion about whether a fact in the case is true.

Hearsay

Hearsay evidence is information that the witness giving evidence did not personally see or hear. Instead, the witness has been informed about the events by another individual. Generally, this type of evidence is excluded.

Opinion

Witnesses are generally not allowed to present their opinions (the conclusions they draw from observed facts) to the court; they are required to testify only about the facts.

However, expert witnesses may testify to their opinion on matters involving their expertise if the court is satisfied that the opinion is based wholly or partially on specialised knowledge. Some areas of expertise include DNA, handwriting, or a doctor/psychologist who has assessed the accused. Expert witness evidence can be valuable to the party who introduces it as it can be persuasive to a jury. However, it is not infallible.

For example, expert witnesses were called to give evidence in the Kathleen Folbigg trial, and the Kulwinder Singh trial.

Tendency

Evidence indicating that a person has or has had a tendency to behave or think in a certain way that suggests that they behaved or thought similarly in the current matter because of that tendency is generally not admissible.

Tendency evidence was relied on in the Claremont Killings case.

Tendency Example:

Suppose an accused is charged with fraud. The prosecution may present evidence that, in previous unrelated instances, the accused has engaged in similar fraudulent activities. This previous conduct would be used to establish a tendency for fraudulent behaviour, which can help to prove that the accused acted with a similar intent in the current fraud charge.

Coincidence

Coincidence evidence is when evidence of two or more similar events is used to show that the witness did something or had a particular state of mind. The idea is that the events are so similar that it’s unlikely they happened by chance. Coincidence evidence is generally not admissible.

Coincidence Example:

Suppose a person, Eva, is charged with breaking into a house in Sydney and stealing electronics. The prosecution seeks to introduce evidence that Eva was involved in two previous incidents where houses in the same neighbourhood were broken into, and electronics were stolen in a similar manner.

First Incident: A house in the neighbourhood was broken into, and only high-end electronics were taken. There were no signs of forced entry, but fingerprints matching Eva’s were found on a window.

Second Incident: Another house in the same area was burglarised in a similar fashion, with the thief entering through an unlocked door and taking only high-end electronics. Eva’s DNA was found on a piece of broken glass at the scene.

The prosecution argues that these incidents are not merely coincidental but demonstrate a pattern, making it more likely that Eva committed the current alleged offence. The similarities between the incidents—the same type of items stolen, same neighbourhood, lack of forced entry—make it improbable that these events happened independently of one another

Credibility

Generally, credibility evidence about a witness is not admissible. Credibility evidence could include evidence of the witness’s ability to observe or remember facts and is often used to strengthen or attack the truthfulness and reliability of the witness or their evidence.

Privilege

Privilege is the right of a witness to resist compulsory demands for information. The general policy behind the concept of privilege means that a witness who is giving evidence can refuse to disclose particular information if it was given to the witness in confidence.

Some forms of privilege include client legal privilege, professional privilege, religious confessions privilege, and the privilege against self-incrimination.

Discretionary powers

Under s135 of the Act, the court may reject evidence if its value in proving something (probative value) is significantly outweighed by the risk that the evidence might:

(a) be unfairly prejudicial to a party, or

(b) be misleading or confusing, or

(c) result in an undue waste of time.

Case Examples

The Claremont Killings

Between 1996 and 1997, three young women were murdered in a popular night spot in Claremont, WA. This case displays the court’s procedures when applying evidence to a case, using a combination of forensic, DNA and propensity evidence (now tendency evidence) to come to a conclusion.

The tendency evidence presented by the prosecution was that there were three other assaults which the accused had pleaded guilty to, and this provided sufficient evidence that the accused tended to attack women.

Kathleen Folbigg

In the 2003 murder trial, several experts, including forensic pathologists and psychologists, gave evidence for both the Crown and the defence. Each expert who gave evidence had specialised knowledge based on training, study or experience, and their opinion was based on their particular area of expertise. As such, the rules for expert opinion evidence as prescribed by the Evidence Act were followed at trial. This meant that Folbigg would be able to be punished in a manner that was in accordance with the law and based on the evidence.

Keli Lane

This case note provides a review of the judgements passed on the trial of Keli Lane, who was found guilty of murdering her child Tegan Lane in 1996. This case demonstrates the application of circumstancial evidence to discern the outcomes of the essential elements of the case, as Tegan’s body was never found, raising questions about intent and what might have happened to Tegan.

Lane chose not to give evidence during her trial. This is commonly referred to as the right to silence.

Evans v The Queen

Evans was on trial for armed robbery at the Strathfield Council chambers. Security cameras captured the robber, who was wearing a balaclava, sunglasses, and overalls, and uttering specific words during the crime. During the trial, the Prosecutor, under cross-examination, had Evans don a balaclava, sunglasses, and overalls, walk in front of the jury, and repeat the words spoken by the robber.

Evans appealed to the High Court, questioning whether it was relevant for the jury to see him dressed, acting like the robber, and saying those words. The High Court found that this was not relevant and, therefore, inadmissible.

Kulwinder Singh

A large amount of evidence was tendered to the court in the Singh case, including physical, written and circumstantial evidence and witness testimony.

The Crown had sought to admit the report of Ms Jatinder Kaur, which addressed various cultural, religious and behavioural elements of relationships in Indian-Punjabi culture and the Sikh religion. The Crown also wanted to call Ms Kaur to give evidence at the trial to assist the jury to understand the cultural relevance of events potentially leading to Parwinder Kaur’s death. The court held that the evidence of Ms Kaur was inadmissible as there was a risk of unfair prejudice towards Singh.

Skaf Brothers Cases

Brothers Bilal and Mohammed Skaf, dubbed the ‘Skaf Rapists’, were involved in a number of gang rapes across Sydney in the early 2000s. The Skaf brothers, along with a number of other men involved in the crimes, faced multiple consecutive trials.

A question during the appeal was whether the jurors’ experiments concerning the lighting and weather conditions at the park was admissible evidence.

A problem arises when jurors rely on external information that has not been presented to the court, as it is evidence that cannot be scrutinised or explained by the accused’s defence team. In this case, the jurors sought their own external information to reaffirm their view of Bilal Skaf’s guilt. This evidence was not able to be cross examined.

Chris Dawson

Courts and investigative bodies were met with complications in locating and acquiring evidence, partially because the disappearance of Lynette Dawson had occurred four decades prior. This resulted in the courts having to rely on circumstantial evidence.

In Dawson, the Crown presented many pieces of circumstantial evidence to the court, including:

- The deterioration of Dawson’s marriage with Lynette;

- Dawson’s affair and infatuation with JC providing an inferable motive for Lynette’s murder;

- The unlikelihood of Lynette disappearing of her own will, leaving her children, financial access, and possessions behind.