Introduction

This resource outlines the legal and cultural landscape of the early New South Wales colony and its impact on the rule of law as applied to Indigenous Australians. It also outlines the competing objectives of the colony – the need to protect Indigenous people and the need to quash resistance to the expanding settlement.

Drawing from Mark Tedeschi AM KC’s book, ‘Murder at Myall Creek: The Trial that Defined a Nation’, it examines the way laws were applied in the settlement. By analysing the work of John Hubert Plunkett and the resulting legal reforms, this resource will illustrate how the rule of law adapts to provide justice.

English tradition in the colonies

The belief that the early colony of New South Wales was filled with law-hating criminals is, ironically, inaccurate.

The convicts and settlers carried with them an innate respect for the laws and institutions of England. As Sir William Blackstone wrote in the Commentaries on the Laws of England, “those who sent to settled colonies carried English law with them as a birthright…”. The laws of England were considered a birthright and inheritance, providing protection of rights and freedoms for convicts and the settlers.

Central to this belief was the courts which served as the central forum for justice and protection of rights.

“What transformed Australia from [a] penal colony to free society was what the convicts carried from Britain in their heads, as part of their cultural baggage. Central to that cultural baggage was belief in the rule of law, belief that the law should and could matter, that it should be respected by their rulers and that it should and could form the basis of challenge to these rulers” (Krygier, 1992).

But what about the Indigenous people who already inhabited the land with their own system of traditions and lores? How was the rule of law applied to them?

Legal status of the Indigenous

Under British law, the Indigenous people automatically became British subjects upon settlement in 1788. In other words, they were subject to English law, entitled to equal treatment under the law and entitled to the protections offered by the law.

This understanding of subjecthood can be traced right back to the English feudal system where there was a sociopolitical hierarchy that indirectly created a system of loyalty to monarch.

However, despite confirmation of the legal status of the Indigenous people by the court in R v Murrell (1836), in practice Indigenous people often remained outside of the law’s protection because “they had no ability to derive any real benefit or protection from it” (Tedeschi pg. 38).

There were three key reasons why the indigenous people often fell outside the protection of the law:

1. The sheer size of the frontier made it difficult to enforce laws adequately and consistently. The scarcity of courts, crown grants and police beyond the borders of the settlement made the bushland hard to monitor. Thus, ownership of these lands often arose from mere possession, physical force and the unspoken bush etiquette that governed the squatters who lived and worked on the land. The rule of law was not present where there was no enforcement of the law.

2. The settlers viewed Indigenous people through a lens shaped by their own culture and religion. Likewise, the Indigenous people had their own unique culture and spirituality which was foreign to the British. English laws were deeply rooted in Christian teachings and as a result, there arose legal barriers that hindered Indigenous access to justice. For example, as we will see in the Myall Creek case note, Indigenous people were not permitted to give sworn testimony “by reason of their ignorance of God” (George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector of Aborigines in 1842). Where you cannot give evidence, it is difficult to take action in Court to protect your rights or to defend yourself.

3. There were significant cultural and linguistic barriers which also impeded Indigenous access to, and knowledge of the law. As British subjects, Indigenous defendants were, in theory, entitled to be tried by peers and equals. However, the true equality and peerage of such jurors has been called into question because they did not share the same language, habits or customs. Often the language barrier meant that they could not even instruct their lawyer. These fundamental differences in language, traditions and social structures made it challenging for Indigenous people to understand or engage with the legal system.

Conflict in unconquered territories

Beyond the borders of the established colony there existed no courts to facilitate debate, and no law enforcement to police the vast bushland. These remote areas were, therefore, beyond the reach of the law and ownership of the land derived from sheer force and possession. It was here that the most brutal and barbaric conflicts took place.

The efficacy of the law was also dependent on the agency of those tasked with enforcing it, i.e., the police. The Waterloo Creek Massacre represented a stark failure of this agency because it was the mounted police who retaliated with a disproportionate amount of force in defence of British interests.

Adapting the rule of law

As we will see in the following case study on the Myall Creek Massacre, the rule of law is an ideal that adapts and grows in each country. Based upon the principles of the English Magna Carta and English law, it needed to grow and take shape as necessary to ensure that the law was applied equally and fairly to all.

Sometimes this happens quickly, while other times justice is achieved through gradual steady reforms.

The Myall Creek Massacre

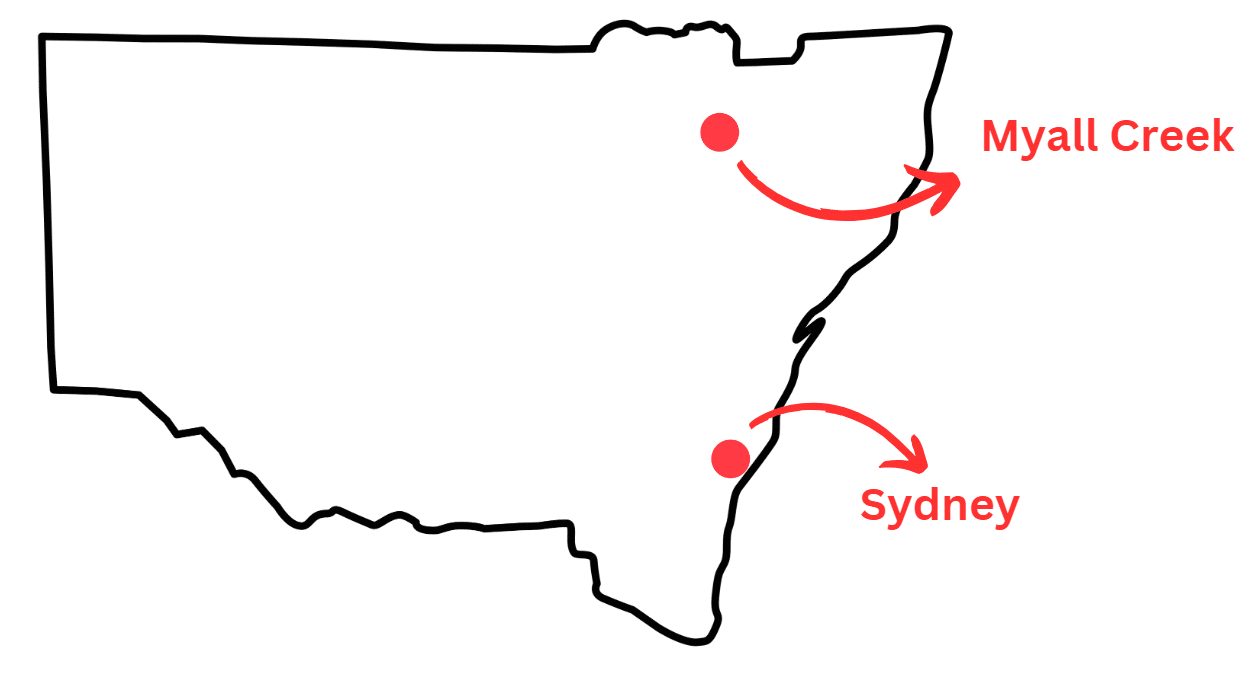

The Myall Creek massacre concerned the cold-blooded murder of about 28 unarmed Indigenous people by 12 British settlers in 1838. The murders occurred about a week’s journey from the borders of the colony in northern New South Wales.

Initially, eleven settlers were arrested for the murders but were found not guilty and acquitted by the jury. John Hubert Plunkett, who served as Attorney General of New South Wales from 1836, was the man responsible for prosecuting the case. Plunkett managed to secure a retrial on a new indictment for seven of the men. All seven men were found guilty, and the judge sentenced them to death by hanging.

Background

Plunkett’s case relied solely on “circumstantial evidence and inferences” (Tedeschi pg. 130). They had witnesses who could testify that the 12 defendants were looking for the Wirrayaraay before the murders, witnesses who could testify that the defendants tied up the Wirrayaraay and lead them away, witnesses who heard gun shots and a witness, well acquainted with the Wirrayaraay, who went to the site after the murders to find burnt and dismembered bodies. The only eyewitness to the murders was an Aboriginal named Davy, a servant at Myall Creek Station, but he was not allowed to give evidence at the trial.

Unlike today, in 1838, if multiple people had been killed at the same time, it was not permissible to prosecute all the murders in a single trial. Instead, the prosecution must pick the victim they believed would produce the strongest case.

Additionally, murder can only be proved if the victim is identified with some degree of specificity beyond a reasonable doubt. So, Plunkett and his junior counsel, Roger Therry, were faced with a difficult task – they had no eyewitnesses who could give sworn evidence, the bodies were burnt and dismembered, making identification near impossible, and they could only pick one of the twenty-eight Wirrayaraay to be the victim.

In the first trial, Plunkett and Therry nominated a man named “Daddy” as the ‘victim’ because he was unusually large. William Hobbs was a key witness who had spent time with the Wirrayaraay. When Hobbs had inspected the murder site, he assumed that the unusually large torso in the ashes belonged to Daddy.

In the second trial, Plunkett and Therry nominated a nameless Aboriginal child, whose rib bone had been found in the ashes.

Legal technicalities

The major issue in this trial and in the legal system at the time was that the law would not permit Indigenous witnesses to provide sworn testimony.

The reason for this was because the spirituality of the Indigenous people was so alien to the British understanding of religion. It was believed that an oath to tell the truth would be meaningless to them because they had no fear of God or the Judeo-Christian understanding of divine judgement for sin.

Consequently, Indigenous people could be tried as defendants, but they were not allowed to testify on their own behalf, present evidence from other Indigenous individuals or initiate proceedings in cases of aggression toward them by the whites or by members of their own race. In other words, they were equally subject to the law, but the law was not accessible to them when they needed protection.

This gap created two problems:

1. First, it meant that many indigenous defendants were wrongly acquitted because they could not present a defence; and

2. Second, the inability of indigenous people to give evidence contributed to the ongoing violence by the settlers against the indigenous people.

Plunkett was outraged by this, and the Myall Creek trials were instrumental in bringing this issue to the forefront of political discussion.

The two trials accompanied only a few other times where the settlers were appropriately punished for the murder of Indigenous people.

It it interesting to note, that for all its inadequacies, this case does illustrate that Australian courts and the rule of law did have the ability “to protect the weak and disenfranchised, to operate without fear or favour, and to treat all people equally, including those on the margins of society” (Tedeschi pg. 265) in order to provide justice.

Efforts for reform

The massacre at Myall Creek and the advocacy by Plunkett was the catalyst for a stream of reforms regarding the rights of Indigenous people. However, given the deep English tradition of respect toward the law and its institutions, these reforms were often slow in order to foster thoughtful and deliberate changes.

Plunkett tried on three separate occasions to pass a bill that would allow Indigenous people to give evidence in court. The initial hurdle to overcome was that of repugnancy to English law and Plunkett was instrumental in lobbying for the Colonial Evidence Act in England to overcome this.

The bill that empowered Indigenous people to give evidence in court was eventually passed in 1876, seven years after Plunkett’s death.

Impact on legal and social institutions

Allowing Indigenous people to give evidence in court marked a pivotal moment in Australian history.

Being a devout Catholic, Plunkett was unwavering in his belief that all people were equal in the eyes of God irrespective of their race, history or religion. Plunkett’s advocacy highlighted the need within a multicultural democracy for a justice system that transcended the divides of belief.

Conclusion

The legal and cultural environment of the early NSW colony played a pivotal role in shaping the application of the rule of law for Indigenous people. Despite the competing priorities, there were notable efforts to ensure just and fair outcomes. The tragic events of Myall Creek and the efforts of figures like John Hubbert Plunkett ultimately demonstrate the importance and efficacy of the rule of law in a multicultural society.

“What the Myall creek murder trials did was to demonstrate that even among all these imagining of the white populations, the colony still had in common with the motherland the fundamental tenet of British law: that justice was capable of being applied equally to all persons if those who apply it are sufficiently determined” (Tedeschi pg. 266).

This reform continues today to provide equality and fairness for all those in Australia who face challenges within our justice system.