Eureka! – Defending Democracy

How the Eureka Stockade shaped the development of democracy in Australia.

The Eureka Stockade had a significant impact on the development of democracy in Australia and was a key moment where the people demanded equal and fair treatment and the right to take part in the democratic process.

This resources follows the development of democracy in Victoria around the time of Eureka.

What was the Eureka Rebellion?

The Eureka Rebellion (or the Eureka Stockade) occurred in Ballarat 1854 during the Victorian gold rush era. In a violent revolt between the Victorian miners and the colony’s military, the rebellion defined one of the most important moments of true representative democracy in Australia, when the people demanded the opportunity to be included – to have a ‘fair go’.

It has often been considered as just a tragic skirmish between miners and a colonial government, but history shows it was much more than that. Through their sacrifice, the miners reinforced key values that are embedded into Australian society today, particularly:

- Freedom of assembly and political participation,

- Freedom of speech, expression and religious belief,

- Freedom of election and being elected.

The events that unfolded in Victoria during the 1850s brought about important introductions in

the Australian electoral process and reminded the government of the significant principles of

justice installed into Australia’s system of law since 1788. It was a time when Australian society

recognised the importance of maintaining the rule of law in upholding human rights. Little did

they know their actions would help shape how a nation would be governed to this day. By the end of the

decade, colonial authorities had finally begun to recognise that colony needed to be run

by the people, for the people.

The following timeline reflects the important and significant developments in how democracy evolved in Victoria during this time.

Timeline of Events

The First Fleet arrives in Sydney Cove (named after Lord Sydney), bringing British Law to the colony.

The colony of New South Wales is ruled by a governor and officials.

The Commission to Arthur Phillip was to govern the colony with prudence, courage and loyalty. Arthur Phillip was to be subject to the law and his own orders were to be compatible with the law

The First Charter of Justice established courts and attempted to ensure that all persons in the colony were subject to the law.

The first civil case involved 2 convicts and a ship’s Captain in July 1788. The convict couple won the case highlighting the beginnings of the rule of law in the new colony.

Meanwhile back in England:

Chartism was a British movement for political reform from 1836 – 1848. Its aims included gaining equality, political rights, and influence for the working class.

Under the New South Wales Act (1823) UK, a Legislative Council is established to advise the Governor.

Its members were all appointed by Britain’s Secretary of State and had the power to advise the New South Wales

Governor in the exercise of his legislative powers.

The Act also established the NSW Supreme Court.

In England, the People’s Charter was signed by leaders of the British working class, called the Chartists.

Chartists demanded electoral reforms, including the vote for all men, and the secret ballot. The British Government considered these people to be ‘trouble-makers’ and were imprisoned or sent to Australia as convicts.

The colony of New South Wales held the first elections for Legislative Council. Mostly a dangerous affair, elections were controlled by wealthy landowners who would only support those who voted for them, or severely punished those who didn’t.

Port Phillip separated from New South Wales to become the colony of Victoria.

The licence was expensive and unfair, and required to be paid whether gold was found or not.

Miners were taxed, but not represented in the government as they did not own the land. They did not have the right to vote or to stand for election to Victoria’s Legislative Council.

Policing methods grew more punitive and brutal as disaffection amongst the miners grew. Gold commissioners, assisted by police, conducted regular ‘licence hunts’ treating miners with cruelty and contempt. Assistant Commissioner Armstrong was particularly brutal.

The British Government gave each colony permission to draw up their own constitutions, with the following requirements:

- The constitutions must be bicameral – two houses of parliament.

The Legislative Assembly (the Lower House) and Legislative Council (the Upper House). - The government would no longer be the governor and his officials.

The ministers and premier must all be members of the parliament. - Responsible governance must be followed

Ministers would be responsible to the parliament and have the support of a majority in the Assembly.

Gold miners were generally well educated in advocating political ideas surrounding democratic rights. As working-class immigrants, many were members of the Chartist Movement, generally coming from countries where revolutions had occurred, such as France and the American Colonies, and strived to gain individual rights and liberties against the authorities. These workers were informed and alert on the desire to achieve independence, regularly expressing their displeasure and expectations publicly.

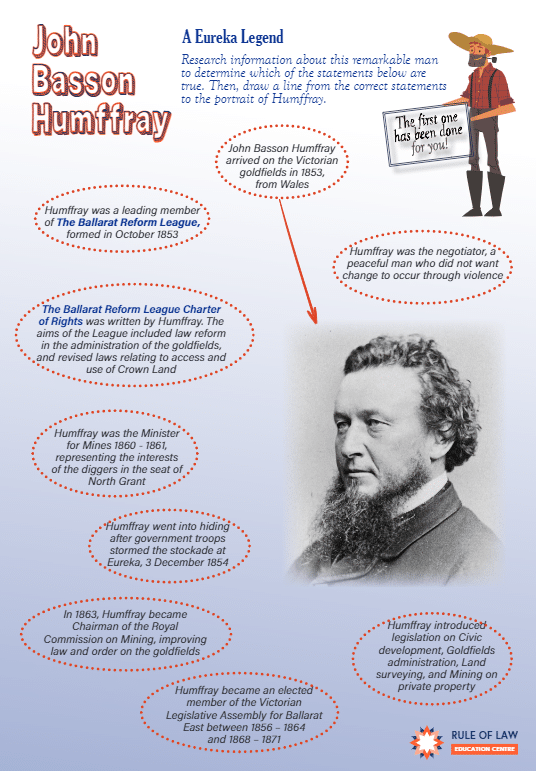

Miners included John Basson Humffray, who arrived on the Victorian goldfields in 1853, from Wales.

The Ballarat Reform League was formed in October 1853. Members included John Humffray and George Black, along with Peter Lalor, Frederic Vern, Raffaello Carboni and Timothy Hayes as leading members.

The aims of the League included achieving reform of the administration of the goldfields and to revise the laws relating to access and use of Crown Land.

Pictured: Worksheet on J. Hummfray

11 November

A mass meeting of miners was held at Bakery Hill on the Ballarat goldfields, where the Ballarat Reform League Charter of Rights was read. This first document in Australia to promote representative democracy was penned by John Basson Humffray.

The People’s Charter demanded:

- The right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws

- No taxation without representation

- Power to be in the hands of responsible representatives of the people, for honest government

- Property qualifications to be abolished for members of the Legislative Council

- Full and fair representation

- Universal manhood suffrage

- Members to be paid to enable less wealthy people to become members of the Legislative Assembly

- Short duration of parliament between elections

- Total abolition of the diggers’ and storekeepers’ licence tax

27 November

The Ballarat Reform League Charter of Rights was presented to Governor Hotham in Melbourne, along with a petition signed by more than 5,000 people across a large swathe of country from Bendigo to Ballarat.

29 November

The miners were angry that their charter was ignored.

Up to 15,000 people gathered at Bakery Hill. The rebels burned their gold licences in protest and the Southern Cross flag was raised for the first time.

30 November and Peter Lalor leads the miners

The Officer in Charge James Johnston responded with a massive digger hunt, arresting miners without licences with brutal force. Outraged miners re-gathered at Bakery Hill, where one of the diggers, Peter Lalor took the lead, delivering a rousing speech, swearing an oath to stand together to defend their rights and liberties:

We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and find to defend our rights and liberties!

Peter Lalor and the crowd then moved to Eureka Flat and built a makeshift stockade, arming themselves with sticks and metal spikes.

3 December – The Battle

Hotham expected a revolt and sent a large force of soldiers and police to disarm the stockade. Arriving in the early hours of the morning, the size and speed of the response caught the rebels off-guard and they were quickly overwhelmed. Over 20 miners and six soldiers lost their lives. Although, as everyone scattered to hide from the authorities, the true number of lives lost was never confirmed. 113 rebels were detained and 13 miners charged with High Treason.

Over the following months, Victorians overwhelmingly supported the defeated miners against the government and the rebels were acquitted after trial by jury.

A Royal Commission investigation found the conditions on the goldfields were unfair. Recommendations included the government abolishing the miner’s licence and twelve new seats be added to the existing Legislative Assembly – eight of them to represent goldfields electorates. An amendment to the Goldfield Act came into effect following the Commission’s Report.

The regime of Goldfields Commissioners, who controlled everything on the goldfields, was removed and replaced with the courts, run by elected miners who held the new Miner’s Right.

Decisions over disputes and claims would now be made by the people, for the people.

The Goldsfields Law Act 1855 (VIC)

Introduction of local courts, with members consisting of people elected by the public, to resolve disputes and claims within the community.

Victoria had produced a mining law, mining judicature, and a mining regulatory system, which was adopted by other Australian colonies and recognised internationally.

The Miner’s Right Act 1855

The Miner’s Right replaced the Gold License on 1 May and cost £1 per annum, instead of the usual £1 per month.

This was historically significant as it gave a miner the right to take a parcel of land to dig for gold, erect a cottage on it, and include a garden. It also gave the right to graze animals on Goldfield land and on vacant Crown Land.

The new system of goldfield’s administration enabled democratic representation leading to:

- Universal male suffrage in 1857, giving the holder the right to vote in the Legislative Assembly

- Improvements in economical and sustainable operations, which remained substantially unchanged up until 1975

- The right to make a residential claim. This led to the development of towns in the gold-mining areas of Victoria, demonstrating the continuation of use of this right within families over many generations

- Socially significant developments in symbolising the attachment of miners over several generations to the freedoms and privileges the Miners Right permitted

The Victorian Consitution was proclaimed on 23 November 1855, after approval by the British Parliament and drafted by Victoria’s first Legislative Council in 1853-1854.

The secret ballot was introduced by the Electoral Act.

Henry Samuel Chapman, the lawyer for the Eureka rebels, drafted the bill which established the new voting system – the Electoral Act 1856 (Vic). Chapman was an Australian and New Zealand judge, colonial secretary, attorney-general, journalist and politician. Government officials released a standard voter form with candidate names printed in alphabetical order. Each voter would enter a private stall and cross out the names of candidates they didn’t support before placing their vote in a sealed box.

Victoria became the first legislature anywhere in the world to adopt this ‘secret voting’ process. An important development in democracy which provided protection for men to cast their vote in secret without recrimination. Britain would adopt the Australian ballot system in 1878, and the United States followed in 1888. The Australian System is used in many countries around the world today.

Peter Lalor was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly, remaining a member of parliament until 1887.

John Bassom Humffray became an elected member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for Ballarat East, representing the interests of the diggers in the seat of North Grant. In 1863, Humffray became Chairman of the Royal Commission on Mining.

Property qualifications for members of the Legislative Assembly were abolished and manhood suffrage was granted.

To learn more about women’s suffrage, go to State Library of Victoria.

On 29 December, Victoria became the first Australian colony to introduce payment of Members of Parliament, ensuring all men could stand for parliament and not only affluent and influential men.

The Legislative Assembly was now a parliament for the people. However, the Legislative Council remained dominated by a squatter and merchant oligarchy. The Payment of Members Act was fiercely resisted at first, as only wealthy men could afford to sit in Parliament. It later became permanent.

Equal division of electoral districts came into effect, enforcing the system of one man, one vote.

The consultation process for achieving federation was long and arduous, with many conventions and conferences held to determine the will of the people across the nation. People became involved through federal leagues, clubs, and societies advocating for unity and change.

The bill for the Australian Constitution (The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900) was passed by the British Parliament on 5 July 1900 and signed by Queen Victoria on 9 July 1900.

The Australian Constitution brought together all the colonies to form one nation and included many of the reforms for representative democracy that came from the Eureka rebellion.

- The Commonwealth of Australia was declared on 1 January 1901

- The new Australian Parliament held the first federal elections on 29 – 30 March 1901

- The first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia was opened at noon on 9 May 1901

- The First Prime Minister of Australia was Sir Edmund Barton