Human Rights Act

Arguments For and Against a Charter of Rights in Australia

Do you think we should have a Bill of Rights or a Charter of Rights and what do you think the pros and cons of that are?

The team at the Rule of Law Education Centre interviewed Lorraine Finlay, Human Rights Commissioner with the Australian Human Rights Commission about human rights in Australia. Lorraine outlined both sides of the debate and highlighted that the key issue centres around who, elected officials or unelected judges, will make the final decisions when two human rights come into conflict.

Brief Explanation

Historical Context

In Favour

Against

Articles

In the interview, Lorraine said:

“It is a really important conversation to be having because we always need to think about how do we want to protect rights and what more can we do to better protect our human rights.”

“People who argue for a Charter of Rights would point to the fact that it offers express clear protection. That it is a way of making human rights accessible to people and it is a way of educating people about what our rights are. It is a way of providing clear guidelines to government – more than guidelines because they’re enforceable – but a clear outline to government of what’s expected of them and citizens with clear remedies if their rights are breached.

The other side, [those who argue against a Charter of Rights], is that if you actually write your rights down in that way, you actually restrict them, because you’re limiting them to what’s written in the charter. Where charters really have challenges is when it comes to determining where the balance lies between conflicting rights. So, when you put a Charter into place, what you’re really saying is, who gets to make the final decision about conflicting rights and how we strike the right balance. In our system at the moment, that’s the Australian Parliament. With a Charter of Rights, that becomes the Australian Judiciary. So those questions are transferred from the Parliament to the Courts.

That is really where the debate lies. Where do you want that final decision to rest.”

Extended discussion on whether Australia should have a Human Rights Act

A Bill of Rights, Charter of Rights or Human Rights Act outlines the fundamental rights and freedoms which individuals are entitled to. If the rights are constitutionally enshrined, they cannot be overridden by law or government; if, however, they are contained within a Commonwealth or State statute, rights may be overruled by subsequent legislation due to the principle of parliamentary sovereignty.

As with any piece of legislation, the courts would be responsible for upholding, interpreting and applying the provisions, or rights, contained in such an Act.

This means that if a human right is encroached upon, the individual is empowered to bring their case before the Court. Here, the Judiciary would determine whether a human right was in fact breached, where the balance should lie between the rights of individuals and the public good, and, subsequently, what remedies are available to the plaintiff. If the breach was Parliamentary, i.e., Parliament enacted legislation that was inconsistent with constitutionally enshrined rights, the Court may strike down the offending legislation as invalid; if it was a breach by an individual/body, they will be sentenced accordingly.

History of Debates in Australia about Human Rights Acts

The drafters of the Australian Constitution believed that the Common Law and the principle of ‘responsible government’ would sufficiently empower people to protect their fundamental rights and freedoms. They believed that the Constitution’s underlying assumption of the division of powers, separation of powers and the Rule of Law would offer greater protection than a designated Bill of Rights.

According to the principle of ‘responsible government’, if a government loses the confidence of parliament, e.g., by violating human rights, the ministers, including the Prime Minister would be accountable to the elected parliament who could replace them with freshly elected representatives who would make different laws.

In essence, the drafters of the Constitution believed that the best protection for human rights in Australia could not be achieved by the creation of a Charter of Rights but rather, by a long-standing tradition of respecting those rights by the people themselves.

The Human Rights Commission, established in 1981, serves as a watchdog for human rights in Australia. However, the debate over instituting a national Bill of Rights has been lengthy and persistent. Notably, there have been two attempts to enshrine human rights in the Constitution. First, during the 1944 Democratic Rights Referendum, and second, during the 1988 Rights and Freedoms Referendum. Both were unsuccessful.

There have also been several attempts to enact a Federal/Commonwealth Human Rights Act. For example, the Human Rights Bill 1973 introduced under the external affairs head of power by the Whitlam Government. However, the passage of this Bill ceased with the double-dissolution of the Whitlam Government.

More recently, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and Queensland have successfully enacted state-based human rights legislation in 2004, 2006 and 2019, respectively.

In 2023, the Attorney-General of Australia referred to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights an Inquiry into Australia’s Human Rights Framework. This Inquiry will consider whether the Australian Parliament should enact a federal Human Rights Act.

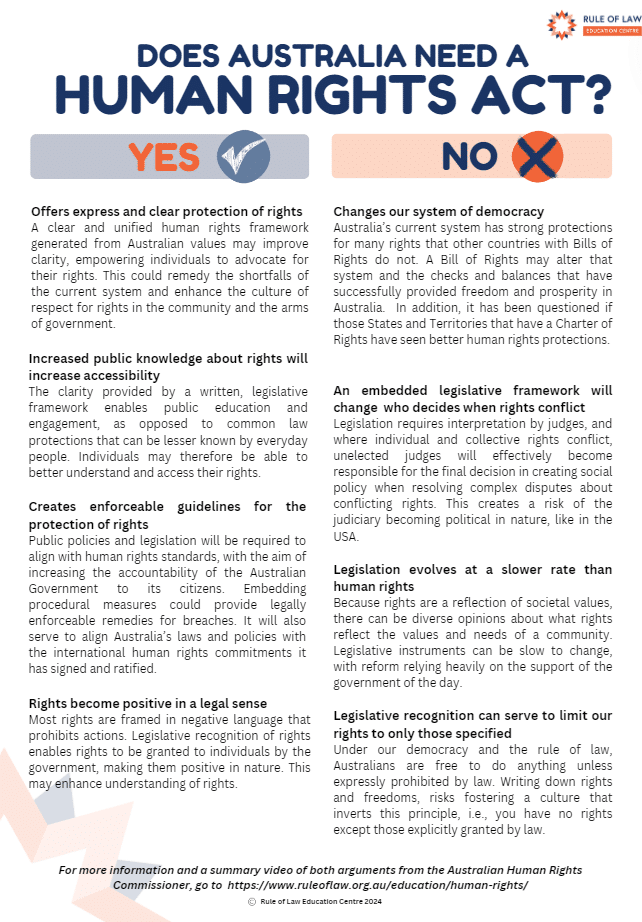

Summary Sheet of Both Sides of the Debate

Drawing from the interview with Australian Human Rights Commissioner and the below research, the Rule of Law Education Centre team have put together this one page document outlining the key points for and against a Human Rights Act in Australia.

Arguments in Favour of a Federal Human Rights Act

1. Offers express and clear protection of rights

a. Supports a culture of rights

A Human Rights Act would reflect and embed shared Australian values into the legal system. This may provide a clear and unified framework for understanding and protecting individual rights. The Act may improve legal clarity, empower individuals to advocate for rights and foster a culture of respect for human rights across the country.

Advocates, like Rosalind Croucher, highlight the current lack of a commonly understood framework and emphasises the need for a Human Rights Act to solidify and promote human rights in Australia.

2. Increased accessibility and public knowledge about rights

a. Remedy shortcomings of current system

Creating a fixed framework for human rights can improve accessibility in several ways.

First, it can establish a clear and consistent standard for what constitutes human rights. This may reduce current ambiguity, help individuals understand their rights more easily and help them assert these rights without confusion.

Second, a standardised framework may make it easier to educate the public about their rights. A rights framework could be integrated into educational systems, public awareness campaigns and professional training programs, making knowledge of human rights more widespread.

Third, a Human Rights Act may remedy the law lag experienced by the Common Law as it struggles to keep up with emerging rights and freedoms.

Fourth, Australia’s current human rights protections are often worded in the negative, i.e., they place an inhibition on citizens rather than an entitlement or granting of a right to something. An example of this is the current Federal discrimination laws. A Human Rights Act may ensure a better balance between positive and negative rights.

Additionally, the current complaint handling process is seen to be ineffective in achieving adequate outcomes for human rights breaches by the government and its departments. Currently, around 2000 complaints per year are handled via mediation where outcomes are not binding or enforceable.

Advocates argue that these shortcomings establish a clear need for updating the human rights framework in Australia. This includes embedding procedural measures within such an Act to provide legally enforceable remedies for breaches.

3. Creates enforceable government guidelines

a. Improves Government Accountability

A Human Rights Act requires public authorities to align policies and legislation with established human rights standards. Individuals will be able to bring government decisions forward for judicial review if their human rights are encroached upon. This ensures that all government actions should comply with the inherent rights of its citizens. The Australian Law Association emphasises that a Human Rights Act would establish a binding code of conduct for those in power, promoting accountability which will ultimately protect the rights and freedoms of individuals.

b. Upholds international obligations

Australia should integrate the rights and freedoms outlined in the UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR into domestic law because these international human rights are not currently enforceable under our dualist system. Consequently, there is a gap between the human rights standards that Australia has agreed to internationally and the actual protections afforded in its laws and policies. A Human Rights Act would bridge this gap by ensuring that laws align with international commitments and by providing a consistent framework for protecting those rights.

Arguments Against a Human Rights Act

1. Changes our system of democracy

a. The current model provides the best protection for rights

Our current system provides the best protection for human rights through a multifaceted framework that adapts to evolving societal norms and values. In our current system, human rights are derived from broad, unwritten principles of justice and equity. This is complemented by “our constitutional arrangement, [where true strength] lies not just in the very boring, technical language of our constitution, which says nothing about rights, but in the unstated assumptions of the law that the judges understand and apply when they have to, and that the people of Australia understand and believe in” (Sofronoff KC).

Human rights in Australia are protected through four key instruments: (1) the Rule of Law – ensuring individuals can act freely within legal boundaries; (2) implied constitutional rights that legislation cannot override; (3) the common law – which is reinforced by the principle of legality, legal precedents and an independent judiciary; and (4) statutes enacted by parliament, which undergo rigorous checks and balances, including bicameralism, parliamentary scrutiny and media oversight.

Ultimately, opponents to the Australian Human Rights Act believe that our current system offers the greatest protection of human rights.

b. Writing down rights will restrict them

Writing down human rights can paradoxically restrict rights by limiting their scope of application to the definitions provided in the legislation. A Human Rights Act could transform previously fluid and adaptable principles into rigid, finite definitions. The flexibility of the common law system ensures that rights can adapt to new contexts and challenges without being constrained by the specific language limitations of codified laws.

Additionally, enshrining rights in written form risks creating a fixed, exhaustive list of human rights that will limit the ability of the legal system to recognise and protect emerging rights. The Australian States that have enacted such Human Rights Acts – Victoria, Queensland and the ACT – do, however, expressly acknowledge that pre-existing rights remain unaffected (Victoria s5 and ACT s7). It is, therefore argued by opponents that enacting a Human Rights Act would either be entirely useless at best because such an Act would create no new rights; or, at worst, counterproductive because rights will be narrowed in both scope and application.

Furthermore, as highlighted by Ben Saunders from Victoria’s Deakin law school when he considered whether State Human Rights Acts changed the way courts apply legislation to protect human rights: “In jurisdictions with human rights acts as well as those without, courts eagerly adopted expansive constructions of the emergency powers and generally adopted a high level of deference to the executive” in rejecting challenges to health and emergency powers. “In other words, human rights acts did not lead to more rights-favourable interpretations of legislation in the Covid cases…There was no case in which courts overturned a decision on the basis that it was incompatible with human rights.”

Under the Rule of Law, individuals are free to act within legal boundaries, meaning you can do anything not expressly prohibited.

Writing down rights and freedoms, however, risks fostering a culture that inverts this principle, i.e., you have no rights except those explicitly granted by law.

At the Rule of Law Robin Speed Memorial Address, Walter Sofronoff KC illustrated this phenomenon with his experience in Russia. While walking in a park in St Petersburg, Sofronoff KC stepped off the path onto the grass. His Russian friend quickly pulled him back, stating that walking on the grass was not allowed. When Sofronoff KC pointed out the absence of a sign, he realised the fundamental difference: in Australia, signs, i.e., laws, indicate what you cannot do; whereas in Russia, they indicate what you can do. Thus, it is argued that writing down rights will both restrict our freedom and fundamentally change our system of democracy.

2. Issues with conflicting rights

a. Human rights evolve

Rights, being a reflection of societal values, inevitably evolve over time, particularly in multicultural societies, like Australia where diverse perspectives coexist. For instance, the concept of property rights or the definition of the right to life may vary drastically among different cultural or ideological groups. By codifying rights into law, we risk stifling the necessary dialogue and evolution that should accompany societal progress.

3. Changes the arbiters of conflicting rights

a. Transfers decision-making power from Parliament to the Courts

If rights are embedded in an Act or in the Constitution, they require interpretation because they are neither absolute nor straightforward. For example, the right to free speech does not permit slander or incitement to racial or religious hatred, and the right to privacy does not allow one to conceal information from tax authorities. Rights often conflict with each other and with the public good. Consequently, if these rights are enshrined in legal documents, unelected judges will be tasked with balancing them to resolve complex social policy issues.

This raises the key question; who should make the final decision?

Is it better to have elected politicians, accountable to the people responsible for determining the balance between individual rights and the common good. Or unelected judges making these decisions?

b. Politicises judicial appointments

Transferring decision-making power to the courts could also increase the risk of politicised judicial appointments, mirroring the American experience where Constitutional interpretation by the Supreme Court is heavily influenced by political considerations.

This could erode the impartiality and independence of the Judiciary, as political parties strive to nominate ideologically sympathetic judges who could interpret the Human Rights Act to align with their policies.

The resulting increase in policy-driven judgements and political influence on the Judiciary could undermine Australia’s democratic principles, blurring the lines between Judicial and Legislative functions and diminishing public confidence in the impartiality of the Judicial system.

The American Bill of Rights

When discussing the effectiveness of the Bill of Rights in protecting fundamental liberties, U.S. Judge Amul Thapar argued that while the Bill of Rights is important, it is not the primary defender of freedoms in the United States.

According to Thapar, the most reliable protectors of rights in America are the separation of powers and the rule of law. He highlighted that countries like North Korea and Russia, despite each having an extensive Bill of Rights on paper, experience significant human rights abuses. This is because the written rights themselves are not enforced; these nations lack the rule of law and are governed by centralised powers. Therefore, although a Bill of Rights is valuable, a system of checks and balances is the most effective protector of individual rights and freedoms because it ensures that citizens are governed by the rule of Law and not by the rule of man. Click here to watch the full interview with Amul Thapar.

Further Reading

Arguments For a Human Rights Act:

- The Hon. Pamela Tate AM KC, submission 61, Inquiry into Australia’s Human Rights Framework (2023).

- Rosalind Croucher AM FAAL, Monash University Castan Centre for Human Rights, A New National Human Rights Framework for Australia (2023).

- Australian Human Rights Commission, Free & Equal, Position paper: A Human Rights Act for Australia (2022).

Arguments Against a Human Rights Act:

- Don’t Leave Us with the Bill: The Case Against an Australian Bill of Rights, Edited by Julian Leeser and Ryan Haddrick (2009).

- Professor Nicholas Aroney, Professor Richard Ekins KC (Hon) and Dr Benjamin Saunders, Submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Australia’s Human Rights Framework: Why the Australian Parliament should not enact a Human Rights Act (2023).

- James Allen, Chapter 8, A defence of the Status Quo (2003).