International Treaty Bodies and the Rule of Law

Introduction

International treaties and associated treaty bodies serve as the foundation of international law, providing a framework for the recognition, promotion and enforcement of human rights both regionally and globally.

While Australia is widely regarded as having a strong human rights record, high levels of personal freedom and a robust commitment to the rule of law, the country has ratified numerous international treaties and conventions. Australia’s engagement in these treaties serves two key purposes: to enhance the protection of human rights domestically and to be a positive example of an active and responsible participant in global affairs.

However, some argue that these international treaties and their associated oversight bodies may undermine Australia’s sovereignty and legal autonomy. These treaty bodies monitor member states’ compliance and adherence to the articles of the treaty in question, which raises concerns about their influence on domestic governance and the potential for decision making to shift from democratic institutions to external, unelected international bodies.

This resource will examine the role of international treaty bodies in promoting and enforcing human rights in Australia, and how international legal obligations influence law making and government policy. It will provide an overview of these treaties and organisations, assess their effectiveness, and explore their impact on state sovereignty and the rule of law.

The Definition of a Treaty

A treaty is the most fundamental element of international law. According to the DFAT, a treaty is “an international agreement concluded in written form between two or more States (or international organisations) and is governed by international law. A treaty gives rise to international legal rights and obligations.”

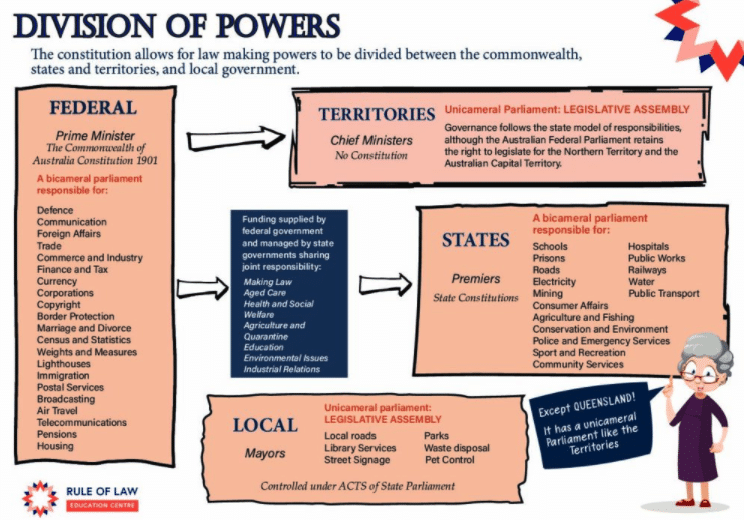

Section 61 of the Australian Constitution allows Australia to enter treaties as an exercise of Executive power. Section 51(xxix) allows the Federal Government to implement those treaties into domestic laws.

Click here to read our resource explaining the treaty process in Australia.

The key international human rights treaties and their associated bodies include:

-

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination – The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights – The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – The Human Rights Committee

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women – The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women

- The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment – The Committee against Torture and the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child – The Committee on the Rights of the Child

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families – The Committee on Migrant Workers

- The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance – The Committee on Enforced Disappearances

Australia has signed and ratified the first seven treaties.

Overview of International Treaty Bodies

When a nation agrees to the legal obligations of an international treaty (a process that differs depending on whether the country follows a monist or dualist system), it commits to upholding and promoting those obligations nationally.

The implementation of these treaty obligations is overseen by a committee, often referred to as a treaty body or subsidiary organ. These committees are responsible for monitoring how well member states adhere to the treaty. The committees are composed of recognised experts, nominated by their respective governments and elected by all member states through a secret ballot. These experts serve four-year terms, which can be renewed, and represent diverse regions of the world, regardless of their own country’s human rights record. Their work on the committee is not a full-time role, and they usually continue to hold separate professional positions during their tenure.

An Australian has been elected six times as a member of one of these committees.

Elizabeth Evatt AC and Professor Ivan Shearer AM served on the Human Rights committee. Professor Phillip Alston served on the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Elizabeth Evatt AC served on the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Professor Ron McCallum AO and Rosemary Kayess served on the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

No Australian expert has served on the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Committee against Torture or the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

According to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, eligible nominees must be persons of high moral characters and due consideration should be given to equitable geographical and gender representation.

Some ECOSOC resolutions establish formulas/quotas for ensuring geographical balance. For, example, ECOSOC resolution 1985/17, on the Committee on ESCR, requires that “due consideration be given to equitable geographical distribution and to the representation of different forms of social and legal systems.” It goes on to explain that of the 18 available seats, 15 must be equally distributed among the five key regional groups with the remaining three seats allocated proportionally to the increase in States per regional group.

Currently, some committee members include Russia, China, and other African and west Asian countries.

This style of election and membership has raised concerns among critics because there are significant differences in the recognition and enforcement of human rights in these countries and some have a particularly poor record of human rights protection. Critics have questioned whether these treaty bodies are democratically valid in Australia or beneficial at all to its citizens, especially given that the primary purpose of these committees is to monitor, support and assist states in the effective implementation of the treaty’s objectives.

Effectiveness of International Human Rights Treaties and Committees in Promoting and Enforcing Human Rights

International human rights committees, such as the Committee on the Rights of the Child, have played a crucial role in the advancement and enforcement of human rights worldwide. They typically achieve this by establishing frameworks and standards that members states are encouraged or incentivised to meet.

1. Implementation of Domestic Laws and Policies that Protect Human Rights

When a government becomes a party to an international treaty, it commits to international legal obligations that require it to respect, protect, fulfil and promote human rights. Often, this commitment translates into the adoption of domestic laws and policies that align with the treaty’s provisions. Given that Australia has a dualist system of law, international legal obligations must be incorporated into domestic law before they become enforceable in Australian courts.

For instance, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most widely ratified treaty globally, has driven significant improvements in children’s rights, both internationally and in Australia. Its ratification has led to the development of new laws and policies that enhance children’s access to healthcare, nutrition, education and protection from violence and exploitation.

Similarly, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), which Australia signed in 1966 and ratified in 1975, forms the foundation for the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) – the RDA.

2. Ensuring Accountability for Human Rights Protection

Member States are generally required to report on their implementation of treaty obligations to the supervising committee. For example, the Australian Government must submit a report every three years on its efforts to comply with CERD, combat racial discrimination and address any areas for improvement brought to it by the Committee.

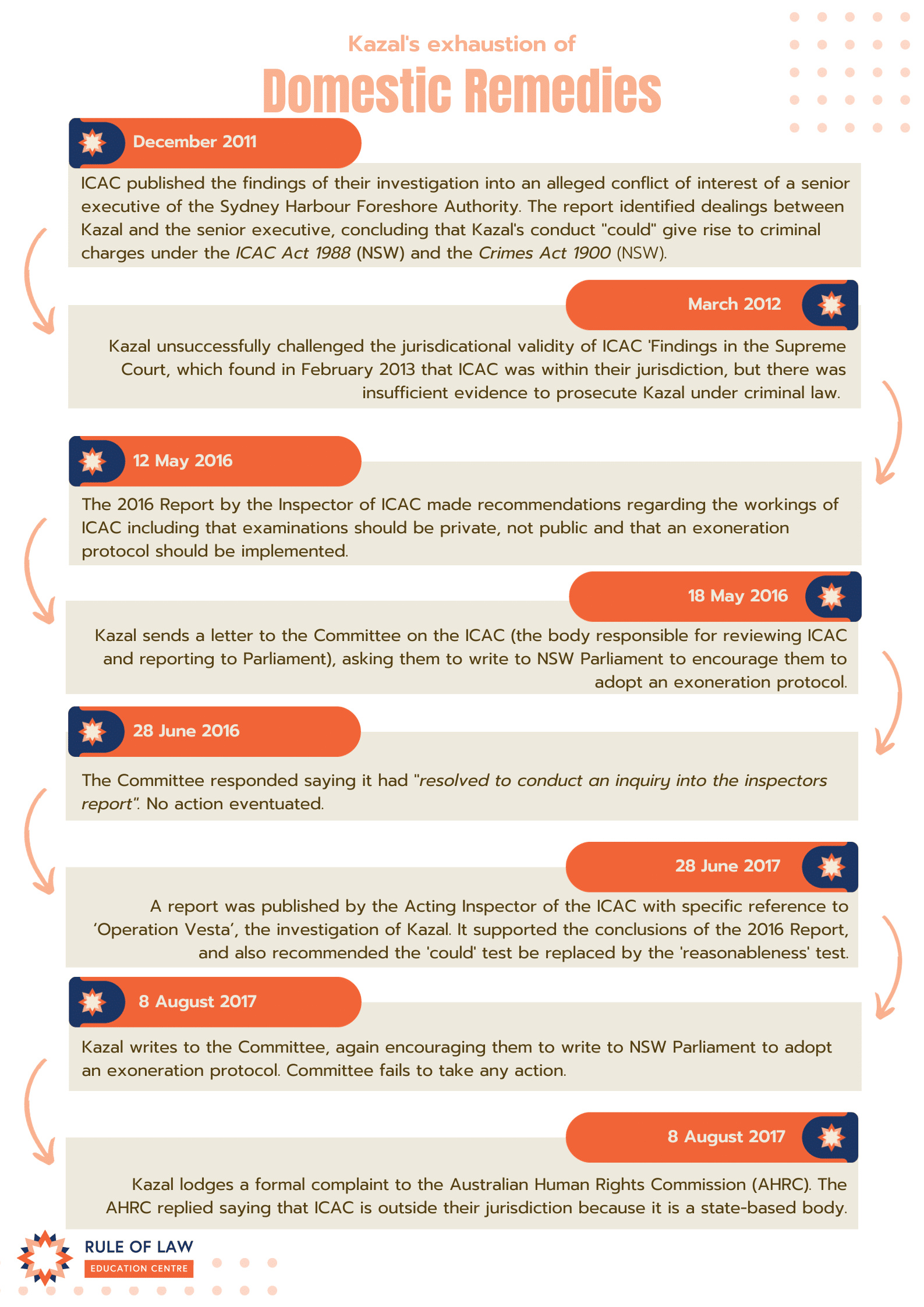

Accountability is further reinforced through complaints mechanisms. International human rights committees can address complaints from individuals who believe their rights have been infringed upon, or from one state alleging violations by another. However, for a complaint to be considered, all involved parties must be signatories to the relevant treaty and domestic remedies must be exhausted first.

For an illustrative example, consider the case of an Australian citizen, Mr Kazal, who lodged a complaint with the UN Human Rights Committee regarding a breach of his rights. The Committee found that procedures of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) violated Mr Kazal’s rights under Article 17 of the ICCPR. The Committee ruled that the Federal Government should compensate Mr Kazal and prevent future violations. Despite this finding, Mr Kazal is still awaiting a response from the Australian Government to the Committee’s recommendations.

Read more about Mr Kazal’s case here.

Ultimately, these committees provide platforms for dialogue, create social pressure, oversee humanitarian interventions, and can issue rulings against governments who breach their obligations. Despite their critical role in setting norms and advocating for human rights, their ability to enforce compliance is limited by the lack of formal enforcement mechanisms and their reliance on voluntary adherence by member states.

3. Reputation and Role Model

Research indicates that the impact of treaties is often more significant through socialisation and normative processes rather than through long-term legal enforcement. Thus, the moral popularity of treaties is vital in fostering a global civic culture and in the advancement of human rights protections throughout the world.

Compared to many other countries, Australia has a comparatively high alignment with international human rights. However, most argue that this outcome was not driven by Australia’s engagement with UN treaties or international legal obligations. Instead, it resulted from the liberal democratic traditions on which the nation was founded. Consequently, the overall impact of internation treaties on Australia’s human rights position has been minimal.

Concerns about the effectiveness of International Treaties and Treaty Bodies

International treaties and treaty bodies, while fostering global cooperation, can present challenges from a rule of law perspective.

1. Diminished Sovereignty

Sovereignty refers to a state’s absolute authority over its internal and external affairs and the people who live within its borders. However, in a globalised world, maintaining a positive international reputation often requires states to cede some degree of sovereignty. Critics argue that international treaties and treaty bodies can undermine national sovereignty by limiting a state’s ability to legislate and govern according to the will of its citizens. This is particularly concerning when international oversight, though important for protecting certain human rights, distances decision-making from the communities affected by the decisions.

The concept of a democratic deficit arises when decision-makers are no longer the elected representatives of citizens. As a result, people become increasingly removed from the law-making process, reducing the power and independence of State democracies. This can transform governance into a technocracy, especially when international bodies are geographically, culturally or economically disconnected from the nations they oversee.

Alexander Downer, former Minister for Foreign Affairs, argued that Australian law should be made in Australia by the Australian people.

“We believe that the protection of Australia’s national interests is most effectively upheld by Australians throughout our Parliaments, our courts and other bodies, and not through UN or other international committees that are ill-suited to playing any direct role in the Australian legal system and many of which are themselves widely recognised as being in need of reform.”

Australians are only legally bound by laws that are passed in Australia and treaty bodies cannot directly change or enact Australian laws. However, the ‘moral or political force’ can be so strong that Australia may feel compelled to incorporate them into its domestic legislation. Additionally, this power often comes from member States who have significantly poorer human rights records or vastly difference legal and cultural backgrounds from those people in Australia for whom the laws are made.

Consequently, many critics question the legitimacy of this influence. For instance, the CERD Committee consists of 18 members, currently, 11 of those members are from African nations, including Algeria and Cameroon. Other countries on the Committee include China, Turkey and Jamaica – all of which have significantly poorer human rights records regarding discrimination.

Professor Ron McCallum AO, former Chairman of the CERD Committee, remarked that “Australia, as a ‘wealthy’ state, can be an ‘easy target’, especially for treaty body members from poorer states.” This reflects a broader concern among western democracies like Australia that they are judged more harshly by UN treaty bodies. A notable example of this sentiment is former Prime Minister Tony Abbot’s comment that Australians were “sick of being lectured to by the United Nations”.

2. Lack of Accountability and Checks and Balances

International treaty organisations often lack the traditional checks and balances found in domestic democratic systems. These bodies may have no clear separation of powers and may oversee the implementation of their own provisions without strong accountability mechanisms. This raises rule of law concerns about fairness and transparency.

Treaties are often negotiated and signed without sufficient parliamentary scrutiny or public debate. In Australia, for instance, treaties are reviewed only after being signed by the Executive to determine whether they should be incorporated into domestic laws. This process significantly limits transparency, and the input people have in the law-making process.

The democratic deficit further complicates rule of law principles because supranational bodies are not accountable to the people, they do not include a representative government elected by the people and their decisions are not subject to scrutiny or consultation. An example of this issue is Australia’s membership to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which was created as a subset of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

3. Bypassing Democracy and law-making by the people

There is also an argument that adopting international treaties, either through the external affairs power or judicial decisions, circumvents democratic processes and bypasses law-making by the people.

a. The External Affairs Power in the Australian Constitution

Section 51 of the Constitutions limits the Federal Government’s legislative power to 39 specific areas. One of these is section 51(xxix), known as the external affairs power, which allows the Commonwealth to legislate in accordance with treaty obligations. Critics point out, however, that international treaties are not confined to these 39 areas, meaning the Federal Government can potentially extend its legislative powers beyond its original constitutional limits.

Many argue that using the external affairs power under section 51(xxix) allows the Federal Government to shift the balance of powers between the Commonwealth and the States more easily than through a formal constitutional amendment, which requires a referendum. Signing international treaties is an Executive action that, as above, does not require explicit approval from parliament or the Australian people.

A prominent example of this is the ratification of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention No.158.

Before this, the Australian people rejected six referendums seeking to give the Federal Government greater control over industrial relations, wage fixing and employment. However, by using the external affairs power, the government ratified the ILO Convention, effectively granting itself the powers that had been rejected by voters on multiple occasions.

Convention No. 158 had a particular focus on the termination of employment. By ratifying the treaty, the Commonwealth Government was empowered to legislate the conditions in which the termination of employment could occur. This legislation covered all Australian workers instead of only those employed under Federal awards. Consequently, Commonwealth industrial laws now have paramount control over all workers, including those originally covered by State awards and those outside the award system entirely.

The implied limitation in the Constitution does, however, act as an additional safeguard to prevent the Commonwealth Government from completely undermining the autonomy of the States. It ensures that the Commonwealth cannot legislate in a way that interferes with the state’s capacity to function as a state, including their ability to manage and employ public servants. This limitation protects states against blatant power grabs by the Commonwealth government, preserving the federal structure and ensuring that states retain control over their own affairs.

b. Legal Implications and Judicial Decisions

The democratic bypass is further exacerbated by some judicial decisions, especially when judges adopt pragmatic or activist interpretations of domestic law. This can lead to treaty provisions being indirectly introduced into Australia through common law.

The 1995 High Court decision in Minister of State for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs V Ah Hin Teoh HCA 20 is a key example:

Teoh, a Malaysian citizen convicted of heroin-related offenses, had his residency application denied on character grounds. However, the Court held that the authorities had failed to consider the best interests of his children. The High Court held that the ratified Convention on the Rights of the Child, although not formally incorporated into Australian law, created a legitimate expectation of procedural fairness. The court overturned the deportation order because the interests of his children were not made a primary consideration in the rejection of his application. The decision expanded judicial power beyond simply applying the law as written by Parliament.

4. Treaties bring no tangible benefits to the Australian people

Finally, there is ongoing debate about whether Australia’s involvement in international treaties offers any tangible benefits to its citizens. Do the advantages of signing international treaties outweigh the concerns raised?

Some argue that Australia’s patchwork approach to human rights protections has led to one of the best human rights records globally. These protections are grounded in democratic principles, including checks and balances and accountability to the people and have not been substantially improved with the ratification of international treaties.

How to address future global concerns

As the influence of international treaty bodies grows and global issues such as pandemics and environmental concerns become more pressing, Nations are faced with the question of how best to address these challenges effectively and legitimately without demolishing the existence of the state or their inherent sovereignty.

With the rise of new global concerns, new international organisations have also been created. These supranational bodies are similarly led by expert panels whose role is to advise on the promotion of public and environmental welfare. However, this raises questions: how will these organisations be funded and where will their authority come from?

The World Health Organisation (WHO), for instance, currently receives only 20% of its funding from member states through membership dues. The remaining 80% comes from voluntary contributions. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – a private entity is the second largest voluntary contributor to the WHO. Notably, 100% of their donation has been earmarked for a specific purpose of their choice. The ability of NGOs and other non-profit groups to wield so much influence over the activities of these organisations is concerning to many critics.

Similarly, the case of Daniel Billy et al v Australia highlights concerns about how these bodies exercise their legal authority and the potential they have to undermine the democratic process as the arbiter of truth.

In this case, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) found that Australia had breached its obligations under the ICCPR by not taking sufficient action to protect a Torres Strait Islander community from the impacts of climate change. The council found violations against articles 17 and 27. Australia was ordered to provide reparations and take meaningful actions […]. But these outcomes beg a question – who sets the standard that defines whether a nation is compliant and who decides whether a state has breached its obligations?

The authority of international organisations like the UNHRC comes from the agreements and treaties that member states voluntarily sign. However, while such agreements are designed to establish common standards for human rights, the growing influence of these bodies raises concerns about accountability and legitimacy. When these bodies make rulings that bind democratic nations, they wield significant power over national democracies without being directly accountable to the people of those nations.

In the case of Daniel Billy, Australia argued that climate change was a matter for international cooperation rather than domestic legislation. However, this raises another issue: should a global body, comprised of ‘experts’ have the authority to define the obligations of a sovereign, democratically elected government? Should a handful of foreign experts, who are not accountable to the Australian public, have the power to decide what constitutes adequate action on climate change?

Australia’s elected representatives are accountable to its citizens and must balance a wide range of policy considerations. However, international rulings like this could force governments to prioritise global standards and mandates over the preferences of their own populations. In effect, these bodies bypass democratic decision making and undermine the will of the people.

Additionally, while international experts may have specialised knowledge, their decisions will often reflect global trends or perspectives from their home countries that might not align with the Australian context or the values of its people. The issue of climate change, for example, is contested, with different countries having vastly different responsibilities, capabilities and approaches. Should Australia’s climate policy be dictated by global authorities, or should it remain under the control of the Australian people?

Case Study: Basel Convention & the Erosion of State Sovereignty

What is the Basel Convention?

In 1992, Australia ratified the Basel Convention, an international treaty designed to regulate the transboundary movement of waste material. This case study examines how the Basel Convention demonstrates a broader trend in international treaties that increasingly constrains national sovereignty and limits the role of Australia’s democracy.

The Basel Convention’s creation was significantly shaped by the influence of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as Greenpeace. While these organisations aim to address global challenges, they can sometimes conflict with national economic and social priorities, and can strain international relations.

NGOs, which are neither elected nor directly accountable, can exert considerable influence over policy decisions depending on the political climate, their public profile and the level of international support for their cause. As a result, countries like Australia can find themselves bound by agreements that significantly reduce their ability to govern independently.

Additionally, some also argued that Australia already had established legal frameworks and regulatory bodies that adhere to international standards for environmental protections. Australia’s

strong track record in this area without the use of treaties suggests that it can effectively manage its environmental responsibilities without the need for restrictive international agreements.

How was the Basel Convention implemented in Australia?

Given that Australia operates under a dualist system, legislation must be enacted for treaties to be enforced domestically. Using the external affairs head of power in s51(xxix) of the Constitution, the Commonwealth Government enacted the Hazardous Waste (Regulation of Exports and Imports) Act 1989 in anticipation of Australia’s membership to the treaty.

Section 4 of the Act defined ‘hazardous waste’ as waste belonging to any category identified in the Basel Convention. However, Australian lawmakers underestimated the Convention’s definition of hazardous waste. They assumed that scrap and recyclable materials, like old batteries, would not be classified as hazardous. As a result, the Australian Government had inadvertently broadened the scope of the law, making it subject to regulation by the multinational Basel Convention Compliance Committee.

The impact of the Basel Convention on Australia and its trading partners

One of the most direct impacts of the Basel Convention is its restrictions on the movement of scrap and recyclable materials, between OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) and non-OECD countries. For example, Australian exporters of computer scrap could no longer ship these materials to countries in the Asia Pacific, where such materials supported local industries and livelihoods. Critics argued that by disrupting established trade agreements, the Convention not only destabilised the global recycling industry but also harmed the economies of countries reliant on this trade.

Allowing an external multinational committee to control trade regulations has had substantial consequences for workers and industries both in Australia and its trading partners. Instead of receiving valuable recyclable materials, non-OECD countries are now flooded with low value waste such as plastic bottles, overwhelming recycling facilities in countries like Thailand.

The situation highlights how international agreements, though intended to protect the environment and associated human rights, can force governments to implement policies that disregard the needs of local industries and economies. Not only can this worsen the very issues they aim to address but it also fundamentally usurps the sovereignty and autonomy of states to control their exports and imports.

What were the implications for sovereignty and governance in Australia?

The Basel Convention has raised concerns about a ‘democratic deficit’. When Australia implemented the Basel Convention in 1989, key decisions about which materials would be subject to export bans had not yet been determined. These decisions were left to a committee based in Geneva, far removed from the Australian public and its understanding of issues regarding infrastructure and trade relationships relevant to Australia. This transfer of decision-making power from national governments to international bodies bypasses the democratic process, leaving citizens with limited input into laws and policies that directly affect them.

This growing separation between decision-makers and the people impacted by the decisions poses a challenge to the rule of law. The rule of law emphasises principles such as transparency, accountability and the idea that laws should be created through a democratic process. However, international treaties like the Basel Convention place significant governing power in the hands of international expert bodies who may prioritise global interests over national or local concerns. As a result, accountability to the people is weakened because these international bodies are not subject to direct oversight by the citizens of the countries affected.

In addition, the Basel Convention illustrates how international agreements can undermine national sovereignty. By committing to such treaties, Australia has ceded some control over its trade policies, particularly in areas related to waste management and environmental standards. This loss of autonomy reflects a broader trend in globalisation, where countries increasingly surrender aspects of self-governance to global expert bodies. For Australia, this shift means that certain decisions are no longer made solely by its elected representatives, but by international committees that may not reflect the specific needs or values of its people.

Conclusion

The Basel Convention highlights the need for careful consideration of the balance between international cooperation and national sovereignty. While environmental protection is an important goal, treaties should not compromise democracy or the ability of nations to govern themselves. As the number of treaties addressing global challenges such as trade, conflict and environmental issues increases, so will the number of regulatory bodies that oversee them. Governments should thoroughly evaluate the powers granted to these bodies before joining any treaty and consider whether participation would lead to tangible improvements that could not otherwise be achieved through domestic efforts. Protecting the principles of self-government and ensuring that treaties do not widen the democratic deficit is crucial in a rapidly globalising world.