Anti- Corruption Bodies

The balance between combating corruption and protecting of individual rights and freedoms.

When Parliament establishes an anti-corruption body, it seeks a powerful tool to eradicate corruption. These bodies are granted extensive powers, but without adequate checks and balances, they can ruin reputations and erode human rights.

The Separation of Powers is designed to provide checks and balances on power. Recently there has been an emergence of statutory bodies that sit ‘outside’ of the Legislature, Executive and Judiciary, intended to act as an additional check on corruption. These bodies are usually created by governing piece of legislation, which provides for their operational framework and jurisdiction.

Due to the nature of their role and the perception of corrupt activities, such bodies are often bestowed with wide reaching powers that can result in breaches of human rights of persons identified and investigated for corruption, impacting on just outcomes and the presumption of innocence for those persons.

The impact of a Flawed System: NSW ICAC

Case Study: Charif Kazal

Highlights the Human Rights breaches where ICAC makes a Corrupt finding but no criminal proceedings.

Case Study: Murray Kear

When the Courts and ICAC make contrasting findings.

Case Study: Nucoal

When Parliament reacts to ICAC findings.

Case Study: Margaret Cunneen SC

When ICAC acts outside its scope.

Case Study: NSW Independent Commission against Corruption

What is ICAC?

The NSW Independent Commission against Corruption (‘ICAC’) was established and is regulated by the ICAC Act 1988 (NSW). It is an independent statutory body created to investigate alleged corrupt conduct in the NSW public sector, with its jurisdiction extending across all NSW government agencies (including the parliament, judiciary and Governor), contractors working within the public sector and people performing public office functions. The ICAC’s powers do not extend to the NSW Police Force, the NSW Crime Commission or private citizens unless their actions are impacting upon or affecting public officials or public authorities, such as in the case of Mr Kazal below. A separate body, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission, is responsible for the investigation of corruption allegations in the NSW Police Force and the NSW Crime Commission.

According to the ICAC website:

“The ICAC aims to protect the public interest, prevent breaches of public trust and guide the conduct of public officials. The ICAC deals with corrupt conduct involving or affecting most of the NSW public sector, including state government agencies, local government authorities, members of Parliament and the judiciary.”

It is not able to prosecute any persons found to be, or suspected to be, involved in corrupt activities, rather must refer these matters to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP), who will then decide whether to prosecute in accordance with The Prosecution Guidelines (s13(1) Director of Public Prosecutions Act 1986 (NSW)).

If a citizen feels that they have been wrongly accused of corruption by ICAC, they can seek a judicial review with the Supreme Court of NSW, but this can only be done on a point of law.

What are some of the problems with ICAC from a rule of law perspective?

ICAC has been established to identify and investigate corruption in order to protect society and improve public confidence in the integrity of the processes and procedures of public administration in NSW.

However, the lack of transparency and accountability, and the public nature of investigations and hearings that ICAC conducts according to its governing legislation, is serving to undermine the processes the ICAC has been created to stamp out. In our resource, What are the flaws of ICAC?, we have outlined four concerns with the NSW ICAC model;

1. ICAC is not a Court but wields immense power

a. As ICAC is not a Court, it does not have the power to make findings of guilt or innocence

b. As ICAC is not a Court, it does not apply the same safeguards to protect an individual’s rights

c. As ICAC is not a Court, it can act as both investigator and judge

2. ICAC holds Public hearings and makes Public Findings

a. Public hearings can jeopardise the right to a fair and prompt trial

b. Public hearings cause reputational harm

3. ICAC’s Lack of options to review corruption findings

4. ICAC’s lack of Exoneration Protocol

By enabling ICAC to act in a manner that undermines the rule of law principles and the human rights that investigated individuals are entitled to in Australia, ICAC is exercising overreach and remains unchecked in its use of power. Further, ICAC remains able to publicly identify individuals as corrupt on its website indefinitely, even after the ODPP has cited a lack of evidence for prosecution and the matter ending without proceedings being initiated. This power has led to the destruction of careers, livelihoods and reputations, and such people are left without remedy or the ability to exonerate themselves.

The best way to understand the flaws in NSW’s ICAC design, is to see examples of real Australians who have not been treated fairly by ICAC.

The Rule of Law Institute of Australia has written extensive commentary about the flaws in the NSW ICAC Model- most recently in its Submission to the Committee on the Independent Commission Against Corruption: Inquiry into Reputational Damage on an individual being adversely named in the ICAC’s Investigations.

1. Case Study: Charif Kazal and Human Rights breaches.

Where, ICAC makes a Corrupt finding but there are no criminal proceedings

Procedural History of Charif Kazal

a. ICAC makes finding of Corrupt Conduct

On Friday 16 December 2011, NSW ICAC published the following findings:

ICAC FINDINGS

The ICAC has found that Andrew Kelly and Charif Kazal engaged in corrupt conduct.

ICAC RECOMMENDATIONS

The ICAC is of the opinion that the advice of the DPP should be sought with respect to the prosecution of Mr Kazal for an offence under the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 of giving false evidence to the Commission that he never intended to settle Mr Kelly’s accommodation account for the May 2007 trip.

ICAC’s basis of its finding of corrupt conduct was that Mr Kazal conduct was intended to influence or could constitute a criminal offence (‘the could test‘). As a result, Mr Kazal was declared ‘corrupt’ by ICAC not because a court found he had broken a law, but because ICAC decided he ‘could‘ have broken a law.

b. DPP decides to not commence proceedings for Criminal Offence

ICAC sought the advice of the DPP as to whether Mr Kazal should be criminally prosecuted. On 28 August 2012 the Solicitor for Public Prosecutions advised ICAC “that the DPP considers there was insufficient evidence against Andrew Kelly and Charif Kazal to commence proceedings for any criminal offence.”

c. Mr Kazal challenges the Jurisdictional Validity of ICAC findings at NSW Supreme Court

In 2013, Mr Kazal challenged the jurisdictional validity at the NSW Supreme Court and the Supreme Court found that the ICAC finding fell within its jurisdiction. (see Margaret Cunneen SC High Court case below when ICAC was found to have acted outside its jurisdiction)

d. Inspector of ICAC views Mr Kazal’s case and calls for Exoneration Process

One check on the exercise of the power of NSW ICAC is the Inspector of ICAC. As outlined on the NSW Government’s website:

The Inspector of the Independent Commission Against Corruption (the ICAC) is an independent statutory officer whose role and functions is to hold the ICAC accountable in the way it carries out its function.

In the extensive report by John Nicholson SC, Acting Inspector ICAC: Report by the Office of the Inspector of the Independent Commission Against Corruption on complaints by Andrew Kelly, Charif Kazal and Jamie Brown, tabled in the NSW parliament, June 29, 2017 Nicholson stated:

The consequence of that course, is that Charif Kazal will never have the opportunity to clear his name.

That finding [of corruption] having been made, however, leaves Charif Kazal with a stain upon his honour, reputation and his right to be considered as a person of good character with no means at law of being able to retrieve or recapture those qualities through recourse to the law or to have the findings of the Commission expunged from the records of ICAC and its publishings on the internet. It has impacted upon his presumption of innocence.

Nicholson’s report stated:

It offends the populous sense of the “fair-go” if a label of corrupt conduct can be place incorrectly upon a person without any real chance of him or her having the label reviewed. Even those convicted of corrupt dealings, and indeed those who have had their appeals finalised, still have mechanisms for having their innocence restored to them should it be the case that they are able to mount a compelling case that they are in fact innocent of a crime.

Nicholson shows he believes it is futile to complain to the office of ICAC’s independent inspector under provisions of the ICAC Act in an attempt to rectify an incorrect finding by ICAC.

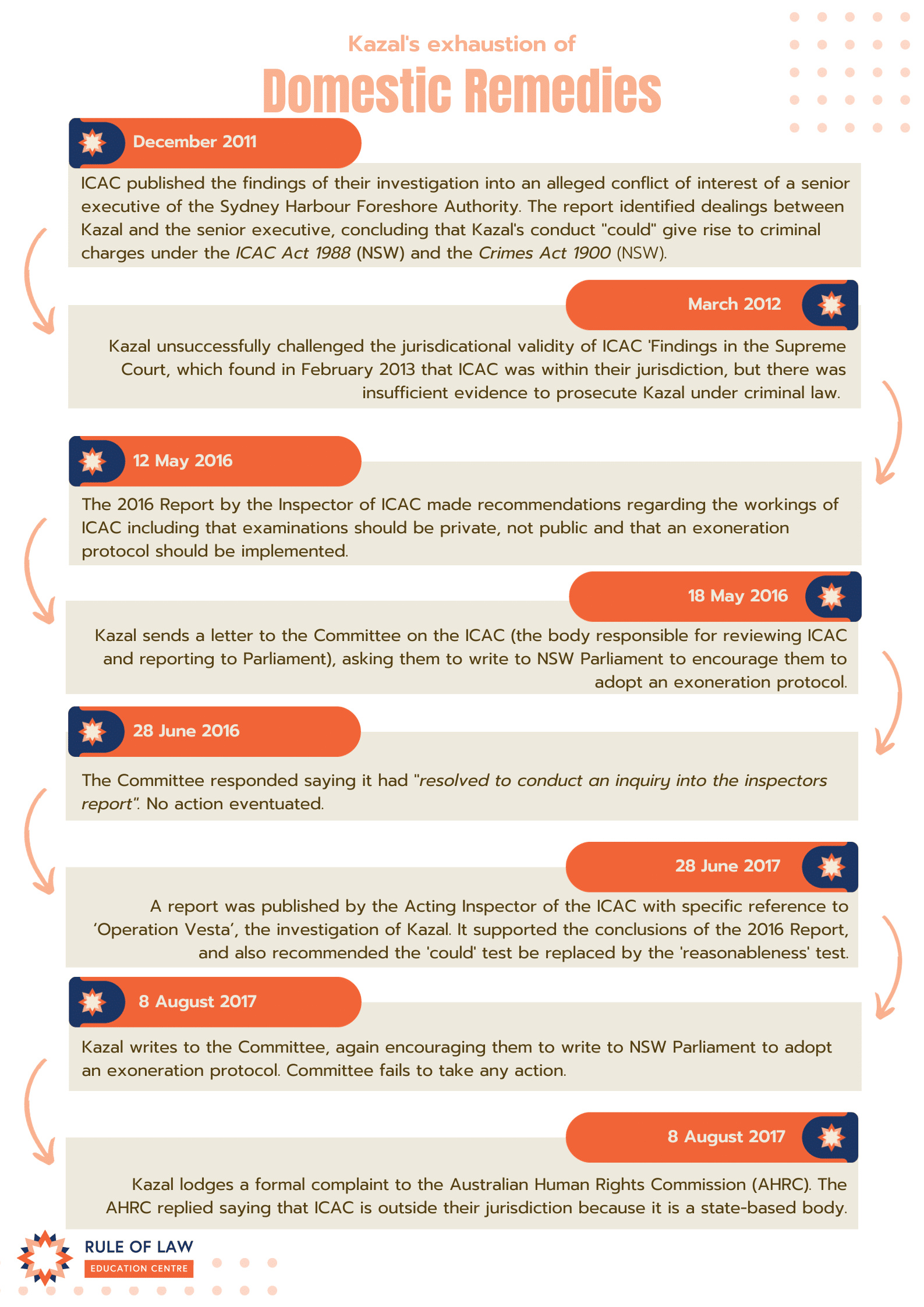

Exhaustion of domestic remedies for justice

As seen above and in the attached infographic, Mr Kazal tried every avenue within the Australian justice system to test the ‘corrupt’ finding made by ICAC.

No exoneration or ability to review the finding of ICAC was available.

Complaint made to the ICCPR for breaches in human rights

The final check on the power that ICAC is the United Nation Human Rights Committee.

On February 2022, Mr Kazal brought his complaint to the ICCPR UN Human Rights Committee.

138 Session (26 June 2023 – 26 July 2023) in late November 2023 released its findings regarding Mr Kazals complaint. It found that certain procedures at ICAC violated international human rights and the committee ruled that the federal government should compensate Mr Kazal and prevent similar violations. The report stated:

“ . . . the inquiry conducted by ICAC, and its adverse public findings made against [Kazal] which he could not challenge, amounted to a violation of [Kazal’s] rights under Article 17 of the Covenant”

The absence of reasons for ICAC’s decisions to hold a public hearing and make its findings public amounted to an arbitrary interference in Mr Kazal’s right to privacy.

It should be noted that the views of the UN Human Rights Committee are not legally binding and the federal government cannot be forced to live up to its treaty obligations. Stay tuned to see if our government is serious about resolving human right breaches when they are raised and whether they take steps to protect Australians.

Final Comments regarding Mr Kazal’s Case

Mr Kazal has been found by NSW ICAC as guilty of corrupt conduct but was not criminally charged nor able to challenge the findings of ICAC.

It would be a mistake, to view this absence of prosecution as beneficial for Mr Kazal. Because there is no merits review of ICAC’s determinations, a criminal trial would have given him the opportunity to have the facts that led to the commission’s finding subjected to scrutiny. Instead, he has been labelled as corrupt and denied access to the one forum that could have determined conclusively whether he was in fact guilty of wrongdoing: a criminal trial. He has had his reputation damaged which impacts his family and his ability to conduct his family business.

The case of Mr Kazal shows that there needs to be some mechanism for those labelled as ‘corrupt’ by ICAC to test the findings in a court of law and some form of exoneration protocol introduced.

Further articles:

The Rule of Law Institute of Australia has made the following submissions calling for changes to NSW ICAC which can be found here.

2. Case Study: Murray Kear

Murray Kear was the head of the NSW State Emergency Service (“SES”) and in 2013 was investigated by ICAC for dismissing a staff member allegedly in reprisal for the staff member making allegations about the conduct about another staff member. In December 2013, ICAC held a public inquiry into the allegation and issued a report in January 2014 finding Mr Kear had engaged in corrupt conduct. In early 2015 Mr Kear was charged by ICAC with dismissing the Deputy substantially in reprisal for the making complaints.

In the case of Mr Kear the full force of ICAC was brought against him for dismissing his Deputy.

- First, the inquisitorial powers of ICAC, search warrants, the obligation to answer questions, the public hearing, the cherry picking of evidence and exclusion in the report of evidence favourable to Mr Kear.

- Then, the public report of ICAC condemning him as corrupt.

- Then, being forced to retire, disgraced without an ongoing wage and being unemployable.

- Then, all the powers and resources of ICAC in prosecuting him with an offense which presumed guilt unless Mr Kear proved his innocence.

Mr Kear’s case went to the Courts and his trial lasted for 16 days.

On 16 March 2016, Magistrate Grogin dismissed the charge against Mr Kear and found him innocent of the charge. In the course of his judgement he stated:

“113. I find that there were many factors behind the dismissal of Ms McCarthy by the Defendant. The inability of Ms McCarthy to assimilate into, co-operate within and lead the SES was, I find, the primary and substantial reason for her dismissal by the Defendant. I am satisfied that the Defendant did not dismiss Ms McCarthy as a reprisal, substantial or otherwise, for her making public interest disclosures. I find that there was no element of revenge, pay-back or retaliation against Ms McCarthy by the Defendant.”

This was a finding not simply that Mr Kear was not guilty but a positive finding of innocence. The effect of the Magistrate’s judgement was that ICAC’s findings of corrupt conduct by Mr Kear was wrong.

However, there was no apology or form on exoneration from ICAC.

Irrespective of the Court’s decision, ICAC believes that their findings of corrupt conduct still stands. In ICAC’s Report to the Premier: The Inspectors Review of ICAC, 12 May 2016 it states:

“Criminal courts do not operate as a mechanism for review of Commission findings. The fact that a person found to have engaged corrupt conduct is not prosecuted for a criminal offence or, if prosecuted, not convicted does not “exonerate” that person from a corrupt conduct finding. In any event, criminal proceedings do not “exonerate” a person from a criminal offence. In a criminal court persons are “acquitted” or found “not guilty”. They are not found “innocent” or “exonerated”.”

Further articles:

ICAC’s ongoing smear of innocent Kear shows the need for reform

Rule of Law Australia Submission to the NSW Parliamentary Committee focusing on the Murray Kear Case and ICAC’s failure to presume innocence and provide fairness and justice

Miranda Devine writes in Daily Telegraph, ‘ICAC victims cleared but still left smeared’

3. Case Study: NuCoal

Chris Merritt outlines the story of Nucoal after ICAC made findings of corrupt findings. Merritt explains what happens when the presumption of innocence is cast aside, not just by a court, but more importantly by a Parliament.

4. Case Study: Margaret Cunneen SC

ICAC investigated Margaret Cunneen SC (former Deputy Crown Prosecutor and President of the Rule of Law Education Centre.)

The investigation was based on allegations of “attempting to pervert the course of justice”. The accusation revolved around an incident where Ms Cunneen purportedly advised her son’s girlfriend to fake chest pains to avoid a breathalyzer test after a car accident, bringing into question whether Ms Cunneen’s conduct amounted to corruption, an attempt to obstruct an investigation or an abuse of power given her position as a senior prosecutor.

As summarised in the Sydney Morning Herald on 17 April 2015,

“At the heart of the Cunneen case was a battle over the meaning of one type of “corrupt conduct” defined in the ICAC Act, involving the conduct of a private citizen that “could adversely affect” the exercise of a public official’s powers. The act says such conduct could also involve one of a number of specified criminal offences, such as perverting the course of justice.

ICAC has long operated on the basis this definition was wide enough to catch cases in which a person allegedly misled a public official to bring about a corrupt result.

This interpretation of its powers was confirmed by an independent report on the ICAC Act in 2005, which said the definition “requires no wrongdoing on behalf of the public official”.

During ICAC’s investigation into the matter, Ms Cunneen argued that the ICAC had failed to clarify why she was being investigated, and that it was therefore acting “beyond its powers”. She brought the case before the Court of Appeal and succeeded in her appeal, though the ICAC soon escalated the matter to The High Court of Australia. The High Court ultimately ruled that ICAC lacked jurisdiction to investigate Ms Cunneen based on these allegations. The court’s decision rested on the interpretation of what constituted “corrupt conduct” within ICAC’s jurisdiction, and it found that the allegations against Ms Cunneen did not fall within this scope.

This ruling invalidated ICAC’s claim against Margaret Cunneen and led to the dismissal of the investigation. The case highlighted the challenges and limitations faced by anti-corruption bodies when interpreting their jurisdictional powers and defining the scope of corrupt conduct, resulting in the investigation being deemed beyond the ICAC’s authority.

On the matter, a Sydney Morning Herald article by Louise Clegg (2015) comments:

Never in the history of the ICAC, have the facts of a case in ICAC’s sights so comprehensively failed to meet the statutory injunction in section 12A. ICAC’s decision to investigate and pursue an allegation that Cunneen allegedly told her son to tell his girlfriend to fake chest pains to avoid a breathalyser test at the scene of a motor vehicle accident amounted to nothing more than a decision to investigate a lie told to a police officer. No one would condone the telling of a lie to a police officer. Nonetheless, it was the glaringly obvious triviality of the allegation that led the legal community to collectively scratch its head, that likely prompted the legal challenge to ICAC’s jurisdiction and led to the High Court being required to grapple with the more technical issue of the meaning of corrupt conduct….

Why on earth, given Parliament’s insistence that ICAC should focus on serious or systemic corruption, was ICAC so intent on devoting scarce public resources to investigating an alleged lie told to a police officer at the scene of a motor vehicle accident?

Notably, even though Ms Cunneen had eventually quashed the ICAC’s allegations, their publication of the matter had severely disrupted Ms Cunneen’s personal life and right to privacy. She has since stated that the ICAC, among other acts of misconduct “attempted to seize [her] phone without a search warrant”. Moreover, the public scrutiny garnered by the investigation severely impacted her career and particularly, her prospects of being appointed a Supreme Court Justice.