Civics education, engagement, and participation in Australia

Submission to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters- Inquiry into civics education, engagement, and participation in Australia

May 2024

Submission Summary

For formalised civic education to be effective it needs to:

- contain key elements, all of which are important for completeness;

reflect Australia’s system of parliamentary democracy (government and laws) and the specific rights and responsibilities that Australians have; - be formally and explicitly taught in schools and universities; and

- be a priority within curricula and teacher education programs.

In Australia, some of the inequitable access to civics education can be attributed to different curriculums containing a variance of content about civics used in each State and Territory, and teacher knowledge of and motivation to deliver civics content.

To address these inequalities, RoLEC recommends that formalised civics education reflect our commitment to parliamentary democracy and needs to:

- Be a mandated education priority across all educational jurisdictions in Australia.

- Be included as a cross-curriculum priority, alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures, Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia and Sustainability.

- List core civics concepts and content for each level of education (K-12) to ensure consistency of civic learning across educational jurisdictions. All State and Territory Education Standards Authorities must be obligated to ensure that these are incorporated wholly into relevant syllabus areas as determined by them.

- Have a system of accountability for those States that take an ‘adopt and adapt’ approach to ensure adequate civics and citizenship content is included in those curriculums.

- Be age appropriate and sequenced across the school experience to ensure that students come to a full understanding of their role as active and informed citizens over time in a parliamentary democracy, maximising their preparation for participation in systems of law and governance as young adults that will continue over their life course.

We also recommend structured teacher education programs specific to civics education be provided for pre and in service teachers and that they:

- Be a priority within all Education Degrees offered by tertiary institutions;

- Be available for both pre-service and in-service teachers; and

- Develop enthusiastic and community minded teachers.

Finally, we recommend informal mechanisms provided by government agencies are balanced, providing multiple perspectives and model desired civic engagement. Specifically, we recommend:

- People and organisations in positions of authority act with integrity and transparency and be held accountable;

- Government leaders model respectful debate to encourage critical thinking and analysis in the community when proposed changes to laws are being decided;

- Governments, specifically those providing education materials, provide accurate and balanced information; and

- Review current civics programs supported by the government to assess if they teach key concepts of Australia’s parliamentary democracy under the rule of law.

Discussion of Issues and Reasoning for Recommendations

What Should Formalised Civic Education Include?

i. Civics education comprises key elements, all of which are important for completeness.

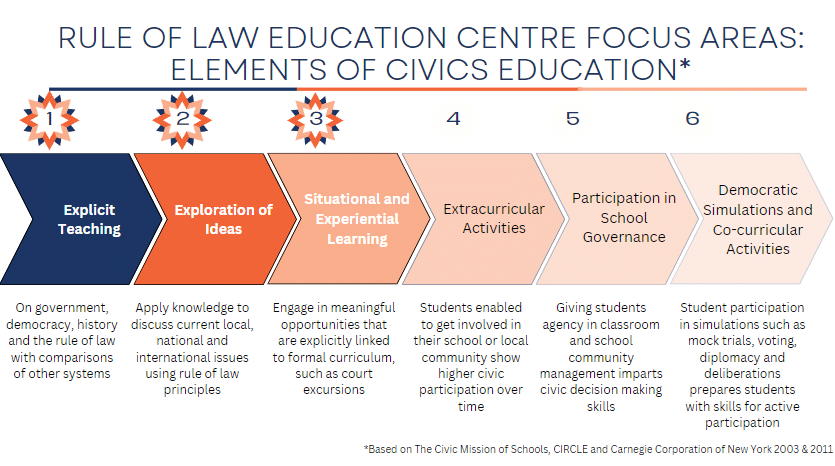

Effective education in civic concepts that properly prepares young citizens for their democratic and civic responsibilities in their future requires a combination of knowledge and skill learning. For a citizen to be adequately informed, they not only need to learn about the skills needed for active participation, but they all need explicit teaching and the opportunity to debate and understand the key principles of our government, democracy and laws.

Figure 1 provides and overview of the core elements of civics education that are needed for successful participation in systems of governance and law.

The specific key elements for formalised Civics and Citizenship education in Australia were agreed upon and articulated in 2012 by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (on behalf of all the States and Territories in Australia). The Statement of Learning for Civics and Citizenship provided a description of ‘knowledge, skills, understandings and capacities that all student in Australia should have the opportunity to learn and develop in the Civics and Citizenship domain.’ ‘The Statements of Learning for Civics and Citizenship … are structured around three broadly defined aspects of Civics and Citizenship curriculums that are considered essential and common.’ These aspects are Government and Law, Citizenship in a Democracy and Historical Perspectives.

Although these key elements of a formalised civics and citizenship education have been identified and agreed upon by the States and Territories, there has been no method of review or audit of each State or Territory’s curriculums to make sure they contain the minimum civics and citizenship content that was agreed upon in the Statement of Learning.

Where those states, such as NSW, embed Civics and Citizenship content across History (and Geography) and the elective subject Commerce, many of these key elements are not covered in any explicit or compulsory way for all students.

This lack of accountability has meant that students’ opportunities for a formalised civics education vary significantly between different States and Territories based upon the individual state curriculum and the education authorities responsible for each state’s curriculum.

ii. Civic Education must reflect Australia’s system of government and the specific rights and responsibilities that Australians have.

Australia is a liberal democracy with a system of compulsory voting and compulsory civic duties, such as jury service. Our system of government and laws, though based on the United Kingdom and United States models, are unique to Australia. As such, it is vital all citizens, whether through birth or migration, are equipped with the knowledge and skills to be active and informed participants in the Australian community through systems of governance and law as is their right and responsibility.

Active participation as a citizen requires specific knowledge and skills. These include:

- the origins of and reasons for the systems of governance and law that we have in place;

- how those systems influence aspects of daily life in the Australian community;

- legal literacy, enabling individuals to recognise and understand their rights and responsibilities as community members. This then serves to improve compliance with responsibilities under the law, and equips citizens with the knowledge needed to seek a remedy through the legal system where an individual’s rights have been breached;

- the ability to have respectful discussions regarding different perspectives on issues of local, national, and international importance; and

- the capability to participate in decision making systems that impact on community life, such as elections across all tiers of government and jury service.

Importantly, civics and citizenship education must reflect the need for active engagement of Australians. It must be more than an education in following the law, like what may occur in the education system of an authoritarian regime.

Instead, the education must reflect our system of democracy under the rule of law where citizens, and those in power, trust and are willing to follow the law and that supports, and where needed, hold those in power to account when they do not act according to the law.

“It is an environment where the population abides by the law because it believes that it provides a fair and just response to the needs of individuals and society as a whole.” (UNODC, Strengthening the Rule of Law Through Education)

iii. Civics Education must be formally and explicitly taught in Schools and Universities

Formalised civics education is needed in Australian schools across the span of the school experience and in universities to create equity and access for all citizens. This formalised education should be:

- explicit and deliberately structured;

- consistent across states; and

- continuous as students progress through the school experience.

Whether the content should be embedded in history/geography or a separate civics and citizenship unit has been debated thoroughly in the past during the formulation of the Australian Curriculum, and is beyond the scope of this submission. The more important issue is whether sufficient formal and explicit content is presented to students either in the embedded subjects or as a stand-alone unit.

Schools and universities must ensure that students are equipped with the right knowledge and skills that represent the Australian system of parliamentary democracy under the rule of law and the rights and responsibilities that come from being an Australian citizen.

This is particularly important as a growing number of students in contemporary Australia are either the children of migrants whose understanding of civic obligations contrasts to those that they have originated in, or migrants themselves. Providing accurate and digestible information about our democracy at school will assist migrant families that may face linguistic and cultural barriers to full civic participation. Creating reliable and relevant understanding in children of migrant parents will assist to bolster knowledge in migrant populations from contrasting political and legal systems. Children of migrant families often become an important information source for familial and cultural community elders, bolstering their ability to participate in community obligations.

iv. Civic Education Must be a Priority in Education Systems

Civics education must be expressly stated as a priority area in education systems across Australia, and have the syllabus supports in place to ensure that civic content is explicitly taught in schools.

All curriculums set across Australia have educational priorities set by the relevant State or Territory curriculum authority. For most States and Territories that follow the Australian Curriculum, these are often cross-curriculum – areas that are incorporated in the content taught across all subject areas as they are relevant across subjects and important for all students to know. For syllabuses to contain content for teachers to explicitly teach across subjects, concepts must appear as a priority area.

In its previous iteration, v.8.4, and the most recently approved iteration, v.9, still being implemented in schools, the Australian Curriculum contains 3 cross-curriculum priorities, which are.

- “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures

- Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia

- Sustainability.

In the Australian Curriculum, cross-curriculum priorities are incorporated through learning area content; they are not separate learning areas or subjects. They provide opportunities to enrich the content of the learning areas, where most appropriate and authentic, allowing students to engage with and better understand their world.”

Source: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/f-10-curriculum-overview/cross-curriculum-priorities

These are mirrored by the Victorian Curriculum v.9.

However, civics education has not been stated as a priority for Australian students undertaking the Australian Curriculum, despite our systems of compulsory voting and civic participation throughout the span of adult life.

In NSW, NESA expressly states the curriculum priorities as such:

“The priorities develop students’ understanding of communities, contemporary issues and the world around them. The priorities are:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures

- Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia

- Sustainability

- Civics and citizenship

- Diversity and difference

- Work and enterprise.”

Source: https://curriculum.nsw.edu.au/about-the-curriculum/capabilities-and-priorities#priorities

When civics and citizenship is one of many priorities (and not one of the top 3 cross curriculum priories of Aboriginal and Torress Strait Islanders, Asia and Sustainability) its inclusion is often left out when juggling the competing interests in a crowded curriculum.

For example, despite being stated as a priority area for curriculum in NSW, civics and citizenship concepts are vastly underrepresented throughout the syllabus, particularly at a high school level. Presently in NSW, the majority of compulsory education in civics occurs in Stage 3 (years 5 and 6) through the mandatory history syllabus. This leaves young adults without recent learning relevant to the civic duties they are preparing to undertake upon reaching adulthood. The majority of civics content in the lower and middle high school curriculums is contained in the optional subject of Commerce, and at senior levels, Legal Studies.

In order to ensure equity across educational jurisdictions, education systems need to prioritise consistent content and standards in curriculum and syllabuses that create the conditions for equitable outcomes and access to rights and responsibilities for all Australians.

Recommendation/Opportunities for Improvement:

Formalised civics education needs to:

- Be a mandated education priority across all educational jurisdictions in Australia.

- Be included as a cross-curriculum priority alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures, Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia and Sustainability, enabling explicit teaching of concepts throughout syllabuses.

- Each State and Territory Curriculum must be objectively assessed against the agreed content as outlined in ACARA’s Statement of Learning for Civics and Citizenship.

Different Curriculum Between Each State and Territory Impacts on Equitable Access to Civics Education.

Even though every State and Territory has endorsed the Australian Curriculum, States and Territories can choose their own Curriculum.

To ensure all students have equitable access to civics education, civic content should be built into compulsory curriculum across States and Territories and should feature in every student’s education regardless of their State, choices in schooling or subject selections.

Each curriculum must include sequential learning that develops concepts over time. The foundations of law and governance and their origins should begin early in the schooling experience, with these ideas progressing in depth and contemporary application across the learning experience. This will couple with the development of critical thinking skills over time. It is important that these concepts are also represented in later high school years in subject areas across the curriculum and are not confined to humanities and social sciences. The teaching of civic concepts is relevant to all aspects of community life, regardless of the career or life path chosen, and as such, concepts should be embedded in learning across the spectrum of subject areas.

Presently, some civic concepts are taught in the Australian Curriculum v.9 in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) curriculum, through the History and Civics and Citizenship syllabus streams. Victoria and NSW are the notable examples who not only educate the majority of Australian School students but who have chosen not to enact the Australian Curriculum for their students.

The Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA), responsible for curriculum and syllabuses in Victorian schools, has opted to largely incorporate the Australian Curriculum into the Victorian Curriculum v.9, adjusting for Victorian priorities. The Humanities Curriculum includes a Civics and Citizenship Syllabus as per the Australian Curriculum, which closely follows the Australian Curriculum syllabus for content teaching across the school experience.

NSW has chosen to ‘adapt and adopt’ the Australian Curriculum, meaning that the NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) chooses what aspects, if any, of the Australian Curriculum to incorporate into the NSW curriculum and where these aspects will be placed in the syllabus. Presently, syllabuses from Kindergarten (K) to year 12 in History (a compulsory subject across K-10), Commerce (an optional subject in year 7-10) and Legal Studies (a senior school elective in years 11 and 12) comprise a limited amount of content contained in the Australian Curriculum related to civics and citizenship.

Concerningly, based on current curriculum and syllabuses used in NSW, the 2022 Report of the State of Civics and Citizenship Education in NSW by the Rule of Law Education Centre found that “in New South Wales, it is possible for students to experience no, or very limited, exposure to civics and citizenship ideas in a historical or contemporary Australian context throughout their entire New South Wales schooling.”

Explicit and compulsory civics concepts in core aspects of the curriculum and syllabus in NSW are vastly underrepresented. As a result, there are very few opportunities for students to be exposed to civic concepts across their school experience, particularly if students do not choose a humanities or social sciences stream in middle and senior high school.

The NSW HSIE/History Curriculum also does not contain sequenced learning of civic content. A student in year 5 may miss two weeks of school and could miss the one opportunity that is included in the primary curriculum to learn about laws, the purpose of laws and law making. If they do not elect to study Commerce or Legal Studies in their senior years, they will have no other opportunity to learn about this key part of civics education.

The NSW Curriculum is currently being developed to address the significant lack of civics and citizenship content. As outlined in our submission to NESA on Version 2 of the K-12 History Draft Syllabus, we have serious concerns about the lack of explicit and compulsory content in the draft curriculum. In particular:

- The lack of content relating to the rule of law such as laws, the judiciary and fair trials;

- The lack of outcomes and core content sequenced over time for key civics content;

- The focus on colonisation only from an Indigenous perspective rather than all different perspectives; and

- The need for a dedicated unit in Civics Education for pre-service teachers

Given that NSW educates just over a third of all students in Australia, this is of great consequence to our democratic future.

It is important to note that although some civic concepts are contained in syllabus streams across Australia as noted above, these syllabuses vary resulting in inequitable access to civics education between States and Territories across Australia.

In order for civic education to be equitable and consistent for all Australian students, a core set of civics concepts and content inclusions should be developed for each year of schooling (K-12) that can be incorporated into syllabuses as set by the relevant education authority. Further, education standards authorities must be mandated to include these at each relevant level to ensure consistent access for all students at the same level of schooling across jurisdictions. These measures will serve to create greater opportunities for students to engage with civics content in a way that is consistent with their age/ stage peers, producing consistent outcomes across jurisdictions.

This content must be designed in a way that is age appropriate for each stage of the learning journey, and should develop concepts over time in a way that explores the origins of the idea or system (‘the why’), discovers the role of those systems and how the operate (‘the what’), and lead to a critical examination of the use systems in a contemporary context, including real life applications, such as case studies (‘the how’).

Recommendation/Opportunities for Improvement:

- A list of core civics concepts and content for each level of education (K-12) be developed to ensure consistency of civic learning across educational jurisdictions. All State and Territory education standards authorities must be obligated to ensure that these are incorporated wholly into the relevant syllabus areas as determined by them. This will produce consistent and equitable outcomes across all educational jurisdictions.

- Learning must be age appropriate and sequenced over time to ensure that students come to a full understanding of their role as active and informed citizens over time, maximising their preparation for participation in systems of law and governance as young adults, continuing over the life course.

- A system of accountability for those States that take an ‘adopt and adapt’ approach to ensure adequate civics and citizenship content is included in those curriculums.

Teacher impact on equitable access to Civics Education.

The variance in civics education across Australia may also be attributed to the variance in teacher engagement with civic concepts. This dis-engagement stems from inbuilt flexibility in syllabuses that leads some teachers to ‘opt-out’ of civics content, teacher knowledge and confidence in teaching civics content and the de-prioritisation of civics as a priority area of teaching practice.

Across syllabuses, many areas of civics and citizenship education are up left to teacher discretion due to the flexibility element built into most syllabuses. Flexibility is built in to allow schools and teachers to opt in and out of optional areas of syllabus content based on factors such as teaching time available, teacher expertise, student interest and teacher knowledge/ interest. If a teacher does not feel equipped and confident to teach an area of content, or if they are disinterested, then they can choose to focus on a different content elaboration contained in the syllabus to meet the teaching hours requirements for that subject area. Inequitable access to civics education is the unfortunate result of teachers choosing their own elaborations and content.

Many of our teacher members have reported that, when given the flexibility of content choice, they opt out of civics-based content and topics due to a number of reasons, including:

- their colonial links being incompatible with current social commentary and a fear of repercussions from engaging with such;

- their own lack of knowledge, leading to a lack of confidence in content teaching. This is particular to both young teachers, who themselves have experienced little civic education throughout their own schooling, and teachers who are teaching out of their area of expertise due to staffing shortages in schools;

- a lack of confidence in leading respectful debate in their classrooms as these skills are not explicitly taught in teacher education courses and rely on good mentoring during teaching practicums, classroom experience and support from school leadership; and

- time pressures of syllabus completion meaning that optional areas can often be uncovered or minimised in order to meet teaching time constraints.

Specific to subject based teaching, evidence suggests that a lack of knowledge in teachers inhibits effective teaching of concepts and relevant terminology needed for students to develop deep understanding. A lack of specific teacher training will lead to the same outcomes with civics content, particularly in teachers that have been school leavers since the de-prioritisation of civics education, migrant teachers who have limited understanding of systems of governance and law in Australia and teachers who are not trained in traditional areas of civics education (humanities and social sciences).

If the quality and quantity of civics education is based upon the teacher’s confidence level in the subject area, inconsistencies arise as to what and how civic concepts are being taught, and often leads to incomplete information related to civic concepts. Based upon research of the decline in civic education and proficiency since 2004, this would also mean that any student who has a teacher who has graduated after 2004 will also have inequitable access to civics education as the teacher will mostly likely be ill-equipped to teach civics-based content.

Further, civics is not stated as a priority area for teacher learning, leading teachers to de-prioritise civics in planning for their own professional growth. Civics education for teachers is not expressly stated as a priority for teaching practice, meaning that it is not a target area for professional development/ learning in either pre-service teachers (student teachers) or in-service (practising) teachers. For example, the NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) is the body responsible for teacher accreditation and professional development in NSW. The teaching priority areas for teacher accreditation and training as identified by NESA are:

“Priority areas are areas of teaching practice that are a priority for all NSW teachers’ ongoing professional growth, and in which NSW teachers must complete PD [Professional Development] to maintain their accreditation.

There are mandatory priority areas and an optional priority area. Teachers must complete at least one NESA Accredited PD course from each of the mandatory priority areas:

- delivery and assessment of the NSW curriculum/Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF)

- student/child mental health

- students/children with a disability

- Aboriginal education and supporting Aboriginal students.

Teachers may also complete NESA Accredited PD in the optional priority area:

- leadership to support the learning outcomes of students/children.”

If civics is to be made a curriculum priority, it must also be made a teaching practice priority to ensure our teachers are properly equipped with the relevant knowledge and have adequate access to professional learning opportunities that support explicit and effective teaching of civics content. In addition, civics and citizenship education should be implemented for all teachers in all subject areas, so they can model active and engaged citizenship within their school communities and be enabled to confidently teach civics content regardless of their subject specialisation.

Civics must be made a priority for teacher knowledge and learning for successful educational experiences. Teacher education programs are needed to address the content and pedagogical demands outlined in the specific syllabus points. This teacher education program needs to:

- Be a priority within University Education Degrees, with a dedicated unit as part of their degree program;

- Be available for both pre-service and in-service teachers; and

- Develop enthusiastic and community minded teachers.

Civics education must be expressly stated as a priority for teacher accreditation with the relevant curriculum and assessment authority. Where civics education is a priority, it follows that there must also be formalised, consistent and compulsory teacher training in civics concepts and content for all pre-service tertiary education courses. Additionally, civic learning should become a professional development priority for all in-service practicing teachers to maximise the opportunities for learning across the school experience and across the curriculum.

Finally, teacher education needs to not only focus on the explicit civics content within the specific syllabus, but also must develop a teacher’s personal citizenship engagement and personal civic skills. Research shows that the degree to which a teacher is politically engaged outside the classroom is a strong predictor of how often they engage their students with issues. Such engagement includes following the news, participating in civic life, engaging in discussing of issues of public concern. This teacher training will include learning how to access relevant and reliable information, how to have an informed debate and different ways citizens can democratically engage to bring about change.

Recommendation/Opportunities for Improvement:

-

Civics education becomes a mandated teacher practice priority.

-

Civics education be made mandatory for all teachers, both pre and in-service. Civics education should not be tied to specific content and pedagogical demands of the syllabus, ensuring all teachers are well equipped to be informed and active citizens and able to provide guidance to all students using the relevant concepts in their area.

Informal Mechanisms That Support Civic Education

Informal mechanisms of education are equally important to the civic education of our citizens, and are two-fold in relation to civic education:

- Those in positions of authority must model the behaviours that we wish to be emulated in communities; and

- As an information provider, government authorities must provide balanced, unbiased views that consider all valid perspectives from the standpoints of law, governance and equity.

To this end, members of parliament and those working for the government must be seen to be in support of and compliance with the principles, values and mechanisms that uphold Australian democracy. This requires a ‘top-down’ approach to modelling democratic and civic practice – citizens who see the example of elected leaders, independent judicial officers and an executive operating with transparency and integrity, engaging in respectful debate, and acting in compliance with the regulations that oversee their operations will be motivated to support and participate in supporting systems. In addition, it is equally as important that there is seen to be consequences for those in authority operating outside of those responsibilities. Citizens that see the value of and trust in the systems that govern them are encouraged to engage due to the validity of their participation in the processes underpinning these systems.

i. Informal Mechanism: Respectful Debate

A key element of our parliamentary democracy are the systems of checks and balances that prevent excessive concentration of power. Many of these checks and balances such as freedom of the press, an independent judiciary and a bi-cameral system with open and transparent law making, are systems of accountability, where those checks and balances make comments and question those in power to ensure their actions are lawful and in accords with our democratic and rule of law principles. It is critically important then, that those in positions of authority through their own actions do not erode these principles and public trust in these important checks. Of particular importance in a parliamentary democracy (as opposed to an authoritarian regime) is the ability of citizens to engage in respectful debate and to question and require accountability for those in authority.

Respectful debate enables Australians to seek and receive information about Australia’s democracy. It enables critical analysis of change and helps Australians be better informed. It allows the differences in our communities to be recognised and accounted for. It enables citizens to be heard. It creates confidence in the decision-making process and respect for the outcome, even if not the individual’s preferred option. Importantly though, it is vital for instilling confidence in the integrity of the systems that we have in place. Respectful debate, that is not censored or controlled by those in authority, allows openness, transparency and testing of facts to ensure accurate information is supplied by trustworthy sources.

To contravene the ability of people to have access to accurate facts and key knowledge representing the multiple perspectives and outcomes of a decision-making process undermines trust in these systems and enables misinformation to flourish. This forces citizens to turn to unreliable sources of information in the absence of balanced resources from government organisations that will provide accurate information to support decision making processes. This in turn leads to the loss of respectful debate where differences of opinion become sources of unrest and dispute rather than a recognised and respected difference of opinion based in consideration of one’s own culture, background and priorities.

ii. Informal Mechanism: Education Materials from Government funded organisations

There is a vast array of informal opportunities for students to receive information about Australia’s government and laws. In particular, the programs at the Museum of Modern Democracy Canberra, the Australian Constitutional Fund at the High Court and other state-based programs such as the Education tours of respective State Parliaments. In addition, there are many online resource hubs supported by the Australian Government to provide information to students about elements of our democracy. One such online resource was Discovering Democracy, which provided excellent material (albeit with dated pictures) but has now been removed from the online site.

However, there is no oversight and audit of these resources to ensure consistency and completeness in accords with the Australian system of parliamentary democracy. Many of these bodies provide excellent resources that inform students about their civic responsibilities and working together as a community. However, in our experience, these informal education materials from government funded organisations look no different to material that is produced by an authoritarian regime.

Before any further government funding is given to civics education, a review needs to occur to:

- Audit those Government Education bodies to assess whether they are promoting Australia’s democracy under the rule of law. If a parliamentary democracy is about active participation, holding those in power to account, checks and balances and respectful debate, then these informal education resources should also reflect these principles;

- Review the current programs to assess their effectiveness. For example, when Year 5 and 6 students visit Canberra, do they come away with an understanding of why there is separation of powers? Do they learn about our Constitution and how it is a document for the people? Do they learn to appreciate why we have a High Court and an independent judiciary?; and

- Learn from past programs. A significant amount of funding was spent on the Discovering Democracy program, yet it is no longer used in schools. The Review of the Discovering Democracy program highlighted the need for content to be included in the curriculum and teacher training. These lessons remain true today as they did with the Discovering Democracy program.

iii. 2023 Referendum and Voice: Failed opportunity to inform Australians about our democracy and encourage better participation.

The 2023 Voice to Parliament Referendum was a perfect opportunity for informal education for Australians to learn more about our system of government and be encouraged to better participate in the electoral system. This, however, was a failed opportunity.

Those in positions of authority did not model behaviours, such as respectful debate that they wished to be emulated in community debate. There was no Constitutional Convention to openly debate or provide community buy-in. Private sector organisations provided most of the information for an extended period of time in support of the Yes campaign, and many organisations, both public and private, made public statements in support of the Yes campaign. Individuals who suggested changes to the proposed wording, or questioned the relevance and consequences of the proposed model were publicly criticised, often by those in Government, and even at times by the Prime Minister.

Rather than providing an informal education in our system of democracy, the 2023 Referendum and the behaviour of those in power, undermined the integrity of the process.

Another informal mechanism that could have encouraged active and informed citizens during the Voice referendum was education materials from government-funded organisations. The only balanced resource that RoLEC found from a government body was the official Australian Electoral Commission Booklet outlining both sides of the Voice Argument. Instead, education materials from government funding organisations only promoted voting YES on the Voice to Parliament.

What should have been provided by government funded education organisations were resources that aimed to inform students about why we have a constitution, what the purpose of a constitution is, how the voting process works, how to have a respectful debate about both sides of the Voice debate and what the proposed changes will mean to our system of parliamentary democracy.

ShapeIf such resources had been developed by government funded education organisations, this would have supported formalised civics education, and provided teachers with impartial information to better participate in decision making within our democracy.

Recommendation/Opportunities for Improvement:

- People and organisations in positions of authority act with integrity and transparency and be held accountable.

- Government leaders model respectful debate to encourage critical thinking and analysis in the community when proposed changes to laws are being decided.

- Governments provide access for citizens accurate and balanced information that presents a range of models for regulation, perspectives and acknowledges potential outcomes of each proposed model.

- Review Current Civics Programs supported by government to assess if teach key concepts of Australia’s parliamentary democracy under the rule of law.