Separation of Powers

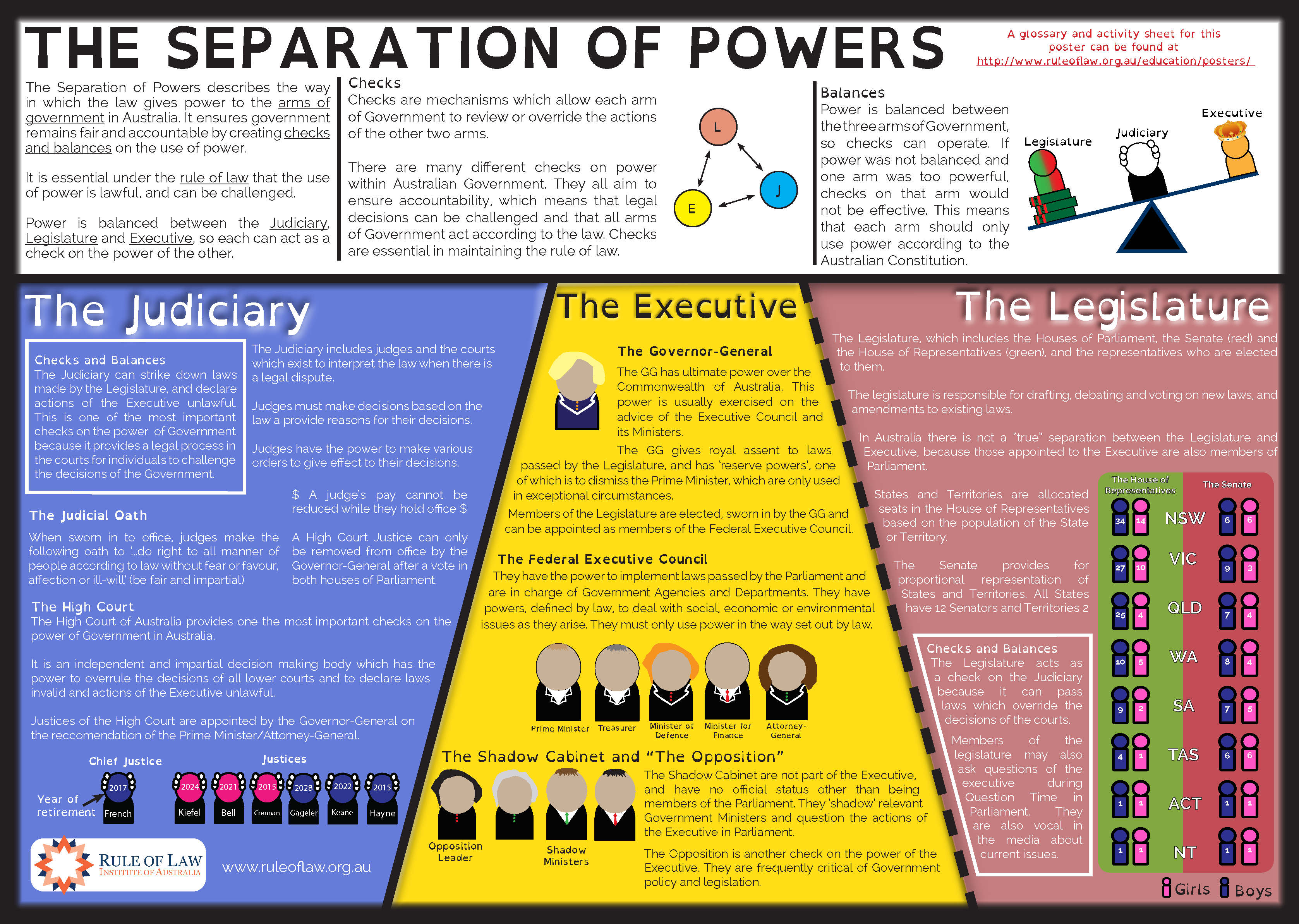

The separation of powers is a concept that requires that the arms of government act as checks and balances on each other’s power.

It is the ultimate protection of human rights as it ensures that it is the law that rules, rather than an arbitrary ruler, with an independent judiciary to determine people’s rights and obligations under the law.

The separation of powers requires that power is balanced between the arms of government, so no one person or body of people becomes too powerful.

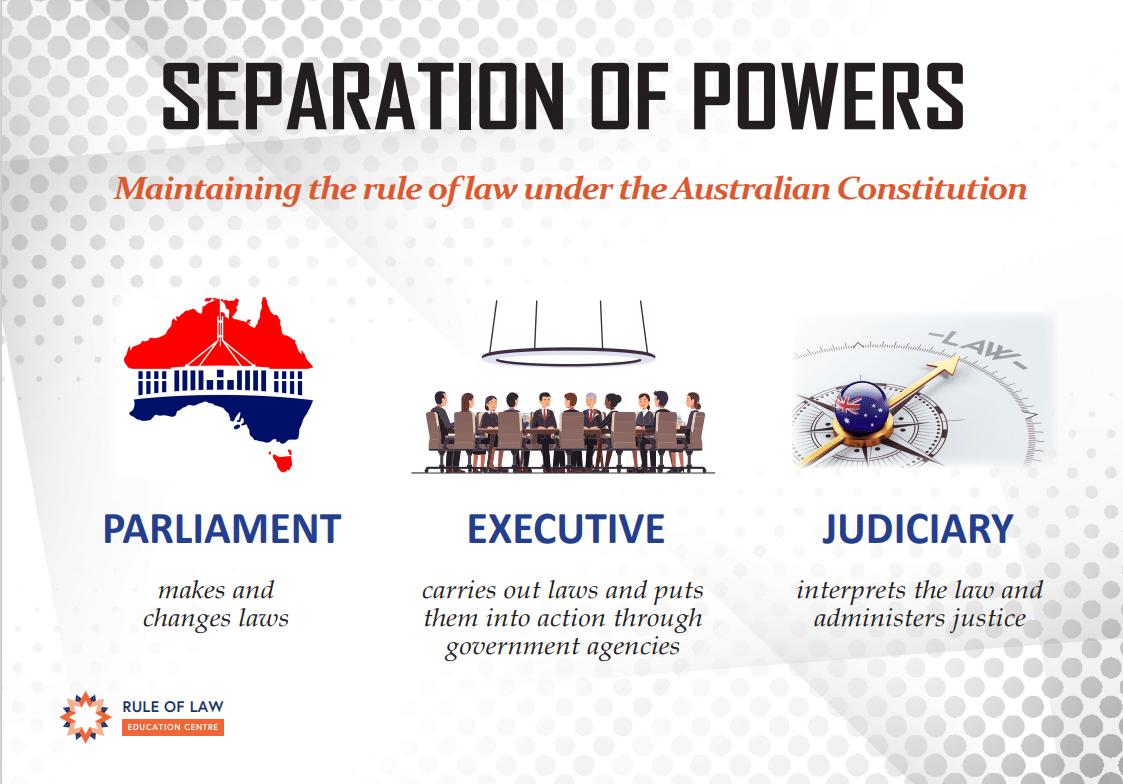

Power is balanced by spreading the power between those who make the law (the parliament), those who enforce/implement the law (the executive) and those who resolve disputes about the law (the judiciary).

The Origins of Separation of Powers

The separation of powers is a concept that stems back to French political thinker, Montesquieu in 1748, who believed that the concentration of power in any single person or group of people as a threat to liberty.

He said:

Constant experience shows us that every man invested with power is apt to abuse it, and to carry his authority as far as it will go….To prevent this abuse, it is necessary from the very nature of things that power should be a check to power….When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner.

The Separation of Powers in Australia

The Australian Constitution is a legal document setting out the basic laws for the government of Australia. It is structured so that the Australian people hold the ultimate power. The fundamental purpose of the Constitution is to define how power is shared within Australia. It outlines where the power lies, who can use it and how it can be used. The Constitution is structured into chapters to create a legal and political system that divides power through the Separation of Powers and Division of Powers.

Chapters I to III of the Constitution outlines the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the Commonwealth as the three separate branches of government ie the separation of powers. The Australian Constitution outlines how power is shared between:

a. Legislature (Parliament) has the power to make and change laws. Parliament is made up of representatives who are elected by the people of Australia

b. Executive has the power to enact law and administer the business of government through government departments, statutory authorities and the defence forces. The Executive includes Australian government ministers and the Governor-General.

c. Judiciary has the power to interpret law and conclusively determine legal disputes. Courts and judges are independent of parliament and government. The role of the High Court as the ultimate independent and impartial arbiter of judicial review

Importantly, the Constitution requires each arm of government operate in accords with the law. The High Court of Australia was established by the Constitution to be an independent arbitar of government action to ensure their actions are according to the law.

Accountability and transparency are also required of government agencies, especially those with coercive powers, to ensure that they act according to the law and not beyond it.

With power comes great responsibility, and the need for ongoing review of such power is essential. This draws in other rule of law principles such as:

Parliament (Legislature): Chapter I

Chapter I of the Constitution establishes the Federal Parliament, which includes the Crown represented by the Governor General, the Senate and the House of Representatives (Chapter I, Parts I–III of the Constitution).

Members of the Lower House (House of Representatives) are chosen by the number of seats from each state and territory. A seat is a geographically defined area which is equally apportioned by population and represented by a single member of Parliament. At the federal level, seats are called divisions and at state and territory levels, they are called electorates. In the Upper House (Senate), members are allocated by a system of proportional representation, which ultimately ensures the composition of the Senate more accurately reflects the votes of the electors.

Section 51 of the Constitution contains a list of topics that Parliament can legislate on. While the states can also legislate on these topics, in the event of any overlap between the laws of the Commonwealth versus the states, federal law will always prevail. Section 52 contains a brief list of topics that only the Commonwealth can legislate upon.

Before a proposed law (Bill) can become an Act of Parliament, it must be passed through both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Bill is then presented to the Governor General who assents to it in the Queen’s name (Section 5). The Bill becomes an Act of Parliament after it has been given this assent.

Section 57 provides a mechanism for resolving any irreconcilable differences between the House of Representatives and the Senate, as disputes can arise on whether a Bill should be passed in its current form. If this occurs, Constitutional power has been specifically created for the Governor General to call a dissolution.

A ‘dissolution’ refers to the act of dissolving something. A double dissolution dissolves both Houses of Parliament and is declared by the Governor-General. This means that all positions become vacant.

An election for both Houses usually follows a double dissolution. If the Bill, or Bills are still not passed after an election, then a joint sitting of the two Houses may be called. This event has only happened once in Australia, in 1974.

Executive: Chapter II

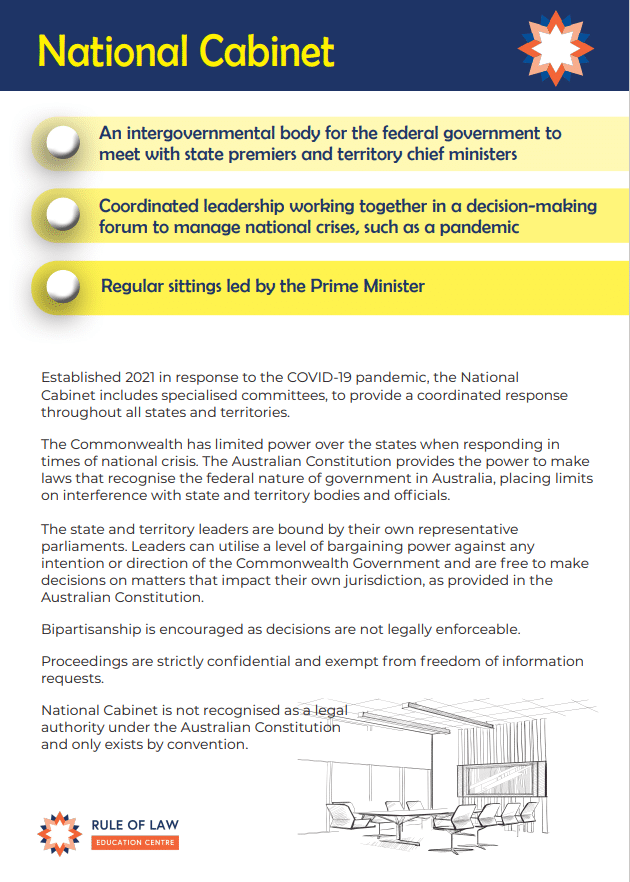

The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested nominally in the Crown; however, in reality it is exercised by the Executive Government of the Commonwealth. The Prime Minister and selected ministers are part of the executive government through a council called the Cabinet. Whilst the Constitution gives the Queen executive power, the Prime Minister and ministers perform the work of executive government.

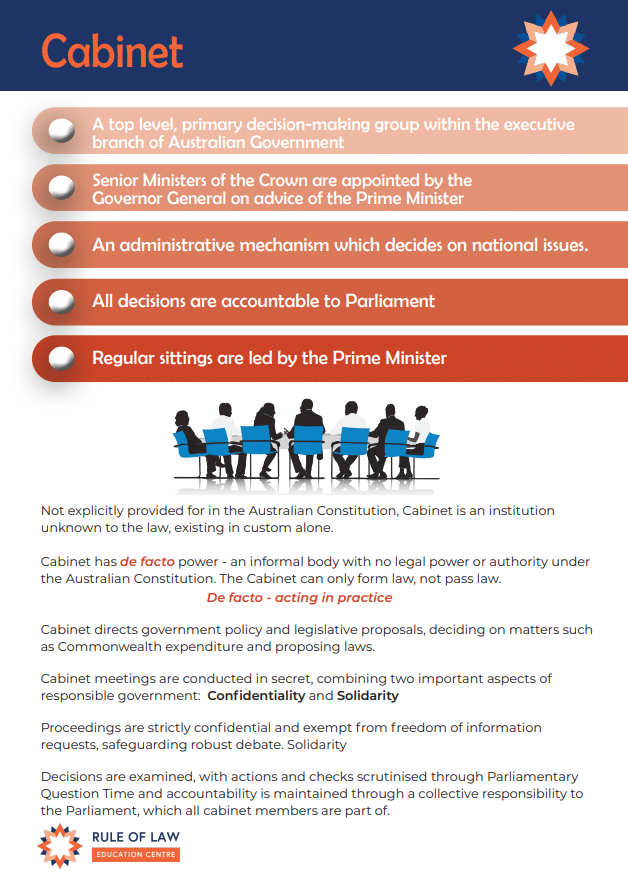

The Cabinet is a central point of decision making in Federal government, but it is not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution. It exists purely as a matter of administrative convenience for government decision making.

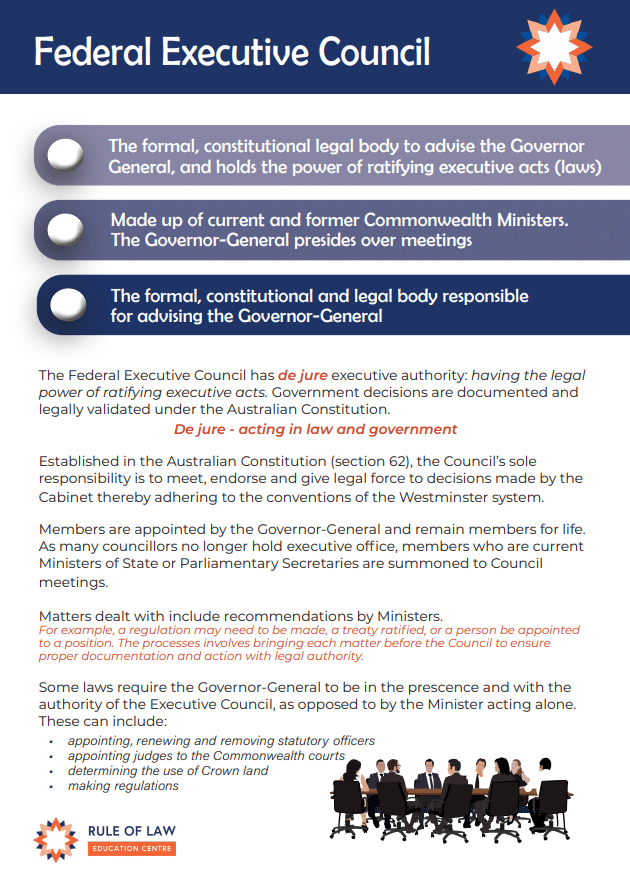

The Federal Executive Council (FEC) is comprised of all ministers of State and advises the Crown, represented by the Governor-General. Its principal functions are to receive advice and approve the signing of formal documents, such as regulations and statutory appointments. While certain decisions of government may be made by the Cabinet, those decisions can only be formally implemented by the Federal Executive Council.

Section 64 of the Constitution provides for the appointment of ministers and the creation of government agencies, to administer the business of the Commonwealth government. Ministers must become members of Parliament and also members of the political party or coalition of parties which holds a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. The Prime Minister must be a member of the House of Representatives, while other ministers can either be members of the House of Representatives or members of the Senate.

Ministers are required to sit in Parliament and adhere to the concept of responsible government. The wording of Section 64 ensures a necessary connection between the executive and the legislature. Any person can be appointed as a minister, but their appointment lapses if they do not gain a seat in either houses of the Parliament. This ensures that only current ministers can take part in executive council business.

In summary, the principle of responsible government supports the executive powers of the federal government, which are almost always exercised on the advice of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Furthermore, according to political convention, the executive powers of the Governor General are exercised on the advice of the Federal Executive Council (FEC).

Posters:

Explaining the difference between the Federal Executive Council, The Cabinet, and the National Cabinet to understand their part in maintaining ‘responsible’ governance.

Judiciary: Chapter III

The High Court of Australia ensures judicial power is kept separate from legislative and executive powers. The High Court and state and territory appeal courts, exercise power of judicial review so legislative and executive branches do not overstep the constitutional and legal limits of their authority.

Chapter III of the Constitution establishes the federal judiciary and empowers the High Court to review government actions. The Constitution provides a key principle of the rule of law in that government should be held accountable and be subject to scrutiny.

Chapter III of the Constitution vests power to federal courts and the courts of the states and territories to exercise judicial review. Section 75 provides for the High Court’s jurisdiction and Section 80 guarantees trial by jury for indictable offences against the Commonwealth.

Section 72 outlines the two pillars of judicial independence – tenure and conditions of service. The remuneration and length of service must remain independent of the executive and legislature to safeguard impartial administration of the law.

Further resources on Separation of Powers

- Check and Balances Explainer

- Australian Constitution Explainer

- Simple Explainers on Democracy and Government (including student activities)

- Separation of Powers Posters