Open and Free Criticism

The rule of law requires open and free criticism of the law and the administration of the law. This principle is underpinned by the concept of freedom of speech, which includes the freedom to express and communicate one’s opinion publicly, freedom of conscience, freedom of belief as well as freedom of expression

Sometimes known as the right to freedom of opinion and expression, people have the right to hold opinions without interference. This extends to any medium, including written and oral communication, public protest and the media.

In a democracy, where the laws are made and administered on behalf of the people, there must be openness and transparency about their implementation. Freedom of speech, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly and association provide opportunities to hold those in power to account for the decisions they make on behalf of the people.

It provides an opportunity for civic participation where the people can participate in the creation and refinement of laws that they must subsequently live by.

Open and Free Criticism: Press Freedom, Free Speech and the Media

The rule of law requires freedom of speech and freedom of the media. People must be free to comment and assemble without fear and be able to criticise the actions of government.

The role of newspapers and journalists in this process is pivotal. The media remains an effective means of promoting accountability in government, and journalists play an essential role in upholding the rule of law. This requires the media (the newspapers, press, publishers) to be independent of those in Government. It also requires journalists to have protections for their sources of information and from legal action that prevents them from reporting in the public interest. Uniform shield laws for journalist’s sources should be implemented across all Australian jurisdictions and should provide certainty and adequate protection for journalists and their sources.

Australian Constitution and Press Freedom

On 1 January 1901, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (1901) came into effect. The Australian Constitution contains an underlying assumption that the rule of law should be upheld in Australian society and democracy. It ensures that all individuals, including those in positions of authority, are subject to and governed by the laws of Australia.

The Australian Constitution does not explicitly safeguard freedom of the press or freedom of expression.

However, the High Court has found an implied freedom of political communication within the text. This implied freedom has played a crucial role in safeguarding the press’s ability to report on political and governmental matters, thus enabling the public to make informed decisions in exercising their democratic rights, particularly in the context of electoral participation.

Common law protections of Press Freedom

The common law is the starting point for the protection of rights, as citizens are free to do anything they like unless it is expressly limited by the law.

As per the High Court of Australia, freedom of speech ‘is a common law freedom.’ The High Court held ‘there are many common law rights of free speech, ’ with the common law recognising a ‘negative theory of rights’ where rights are marked out by ‘gaps in the criminal law’. Attorney-General (SA) v Corporation of the City of Adelaide (2013) 249 CLR 1, [145] (Heydon J)

The Courts have also held, however, that freedom of speech is also not absolute and there may be times when it may be restricted.

International Human Rights and Press Freedom

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) considers freedom of speech.

Article 19 states:

“1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

( a ) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

( b ) For the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals.”

Although Australia has signed and ratified the ICCPR, only some articles have been enshrined in statutes such as the Racial Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) and Anti Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW).

In her interview with the Rule of Law Education Centre about Freedom of Speech, Lorraine Finlay, Australian Human Rights Commissioner said;

“human rights are often expressed through law, but they’re not a gift of the law, because if human rights are only found in laws that are written by government, if they’re the gift of government, then government can take them away.

And my view, and it’s set out in the Universal Declaration, is human rights are inherent in us. They’re certainly expressed through legislation, but that’s not actually where they ultimately reside.

And it’s really important that we all think about what our human rights are, why they matter to us, and what we can do to help strengthen human rights in Australia without just leaving that to be entirely the responsibility of government.”

Press Freedom and the Magna Carta

The laws of England, with legal principles and protections developed over many centuries, starting with the Magna Carta in 1215, The Habeas Corpus Act in 1679 and the Bill of Rights in 1689.

The Magna Carta, an important medieval document, was sealed in 1215 by King John of England. King John, known for his arbitrary and cruel rule, was compelled to agree to follow the laws of the land, marking a significant moment in the establishment of the rule of law in England.

The Magna Carta introduced the concept that all citizens, including the King, are bound by the law.

Magna Carta: Punishment only under the Law

Clause 39 of the Magna Carta embodies the fundamental principle that punishment should be administered only in accordance with the law. This means that individuals enjoy the freedom to conduct themselves as they wish unless specifically restricted by law.

Clause 39 reads:

“(39) No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land”

As outlined by Malcolm Stewart in his article Freedom of Speech and the Rule of Law, clause 39 of the Magna Carta highlighted:

“The absolute supremacy or predominance of the law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power. We are ruled by the law and the law alone. We can be punished for a breach of the law but nothing else.”

Although not explicitly stated in the Magna Carta, freedom of the press is a crucial factor in upholding the rule of law. Firstly, pre-publication censorship through press licensing laws restricts the freedom of information before it is even expressed. Under clause 39 where punishment is only for breaches in the law, prepublication censorship limits the ability to receive or impart information before a breach has even occurred and before a law has even been broken.

Secondly, the Magna Carta’s significant legacy includes the power to criticise the King and hold him accountable. Restricting the ability to question those in power would be contrary to the spirit of the Magna Carta, limiting criticisms to only those approved by the King.

Open and Free Criticism: Academic Freedom

In his paper ‘The Peter Ridd case- a pyrrhic victory for James Cook University’, Chris Merritt writes “Academic freedom is a category of freedom of speech where the public interest in protecting this right predominates.. it outweighs any assertion that people need to be protected from the risk of professional embarrassment where shoddy work is exposed…

According to Mill’s great essay, On Liberty, whilst a prohibition upon disrespectful and discourteous conduct in intellectual expression might be a “convenient plan for having peace in the intellectual world”, the “price paid for this sort of intellectual pacification, is the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind.”.

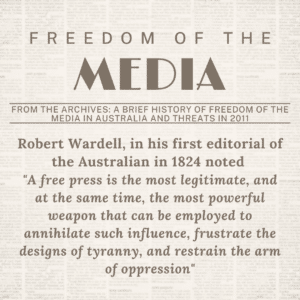

Upholding the Freedom of Press in the Early Penal Colony of Australia

In 1788 when the British established the penal colony of New South Wales, it was governed by English Law.

As Sir William Blackstone wrote in the Commentaries on the Laws of England, “those who sent to settled colonies carried English law with them as a birthright…”. The laws of England were considered a birthright and inheritance, providing protection of rights and freedoms for citizens.

Upon Governor Darling’s arrival in New South Wales in 1825, the NSW Act 1823 (UK) had just been passed. This Act provided checks on the Governor’s power with a Legislative Assembly and the NSW Supreme Court.

The NSW Act required the Governor to consult with the Chief Justice of the NSW Supreme Court before passing any new laws to ensure they were not ‘repugnant’ (conflicting) to the laws of England.

Press Freedom challenged in the early colony

During this period, the colony of NSW consisted of convicts, ex-convicts, children of convicts, and free settlers. The Sydney Gazette was a newspaper that published favourable articles about the Government. However, other newspapers such as The Australian and Sydney Monitor, advocated for freedom of the press and the right to critique those in power.

In 1827, Governor Darling, displeased with critical articles published by The Australian and Sydney Monitor, sought to impose an annual license fee on newspapers. This fee would grant the Governor the authority to decide which newspapers were permitted to publish and could be utilised to censor any publications that opposed his leadership.

Before the law could be passed, Chief Justice Forbes was required to certify that it was not repugnant to the laws of England. There was a heated dispute between Governor Darling and Chief Justice Forbes regarding the passage of the law and whether it was ‘repugnant to the laws of England.’

Press Freedom upheld in the early colony

Chief Justice Forbes refused to allow the Governor’s proposal to enact legislation that would implement a licensing system that curtailed the freedom of the press.

Forbes wrote his reasons in a letter:

“By the laws of England… every free man has the right of using the common trade of printing and publishing newspapers; by the proposed bill this right is confined to such persons only as the Governor may deem proper. By the laws of England, the liberty of the press is regarded as a constitutional privilege … every man enjoys the right of being heard before he can be condemned either in his person or property... [by the proposed bill] the Governor, with the advice of the Executive, may revoke the licence granted to any publisher at discretion, and deprive the subject of his trade, without his having the means of knowing what may be the charge against him, who may be his accuser, upon what evidence he is to be tried, for what violation of the law he is condemned. The Governor and Council may be both complainants and judges at the same time, and in their own cause—-that cause one of political opposition to their own measures, and consequently their own interests, of all others the most likely to enter into their feelings and influence their judgment.”

[Historical Records of Australia, I, xiii, p.293-4]

Forbes’ view would have been derived, in part, from his reading of Blackstone’s Commentaries, which Chief Justice Forbes brought with him to the colony.

The Blackstone Commentaries (Volume 4) stated:

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications… Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if (an individual) publishes what is improper, mischievous, or il-legal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.”

The freedom of the press and freedom of expression, as articulated by Blackstone, are fundamental human rights. Freedom of speech encompasses not only the right to hold an opinion, but to also discuss and express those opinions, and the freedom of belief as well as freedom of conscience. Consequently, freedom of the press should not be subject to prepublication censorship, as this would suppress the voicing and debating of opinions.

Forbes expressed a similar sentiment when he stated: “Every man has the right to be heard before being condemned, whether in his person or property.”

Blackstone also emphasised that freedom of the press is not an absolute right. There are instances when freedom of speech can encroach upon other rights and there should be consequences for such ‘temerity’.

As Forbes contemplated passing press licensing laws, considerations around the suitability of freedom of the press in a settlement established as a convict colony would have been made. This would involve assessing whether both convicts and non-convicts should be entitled to the protections offered by a free press. Additionally, Forbes would have evaluated the necessity of limiting these rights, especially if the colony was in a state of emergency and the overall safety of the community was at stake.

As explained by Sir George Murray, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, on 30 August 1828 in considering Forbes’s decision to refuse the press licence:

“…of such extreme urgency as to supersede the application of all ordinary principles of law”, and for such emergencies “temporary provision” would have to be made. “But in any ordinary state of society,” he concluded, “the previous condition of obtaining a licence must not be required. ” Cases may arise of “such extreme urgency to supersede the application of all ordinary principles of law” but such emergencies were only to be temporary measures.“

Quote taken from Sir Francis Forbes by CH Currey

Resource on Free Speech

- RoLIA Submission on Public Interest Disclosure Bill 2013, submission

- Limits to freedom of political communication in Australia, essay

- Free speech, rule of law and political debate in Australia, research guide

- Peter Ridd’s case- a pyrrhic victory for James Cook University, paper

- Robin Speeds Paper from 2011 on the history of Freedom of the Media in Australia and challenges in 2011