In the first post of 2017 in our ongoing collaboration with New South Wales Young Lawyers’ International Law Committee, Joshua Wood explores the intricacies of international customary law and the rule of law.

‘The most difficult thing about international law’, Professor G.R. Watson of Columbus School of Law once wrote, ‘is finding it.’1

Perhaps the field where this rings most true is that of ‘customary international law’. Despite appearing in treaties, international court decisions, and United Nations resolutions (and in fact being older than the United Nations itself), customary international law is a concept rarely discussed in mainstream public discourse. Yet it has profound consequences for the international rule of law.

Defining customary international law

Like many concepts of international law, there is unfortunately no comprehensive definition of customary international law to which there is total agreement. The closest we have to a universal definition is and adopted by nearly every country (or ‘state’) in the world as members of the United Nations.

One authority that has attempted to build upon this (rather limited) definition is the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which was set up under the Statute. Despite being(Statute Article 59), the ICJ is the “principal judicial organ” of the United Nations and its decisions tend to be followed by other international courts.2 Its decisions are therefore of great influence for international legal scholars and jurists.

The ICJ and Customary International Law

In North Sea Continental Shelf the ICJ explained that there are actually two types of customary international law.3

The first, often overlooked, type comprises legal rules that are logically necessary and self-evident consequences of fundamental international legal principles. For example, because it is a fundamental legal principle that each state is sovereign, it is logically necessary (and thus customary international law) that the sovereignty of each state extends throughout that state’s own borders.

The second type, which is the focus of this article, comprises rules called “opinio juris” (‘an opinion of law’). To be considered opinio juris a rule must satisfy two criteria:

- It is settled and uncontroversial practice of states to act (with general consistency – Nicaragua v. USA)4 in obedience to the rule; and

- States obey this rule because they consider themselves legally bound by it (i.e. not just because of tradition, politeness, or convenience).

The ICJ has said that evidence of satisfaction of these criteria mainly comes from how states physically act (Libya/Malta),5 but it can also come (to a lesser extent) from the treaties they adopt and other governmental actions.6

Some opinio juris rules are sensible and unsurprising – for example, that acts of self-defence must be necessary and proportionate (Nicaragua v. USA7).

Others are much more niche, such as Costa Rican inhabitants’ right to subsistence fishing on their side of the San Juan River border with Nicaragua (Costa Rica v.Nicaragua).8

The Problem of Clarity in Customary International Law

Considering that the binding rules of opinio juris are created solely on the basis of what states believe and how they act, we can see why academics have variously described customary international law as “scattered”9, “primitive”10, and “mysterious”11. Any unwritten body of law that materialises and develops on this basis is bound to be blurry and raise awkward questions.

Some questions:

Is it not paradoxical that a state has to believe a rule is legally binding before it actually becomes law?12

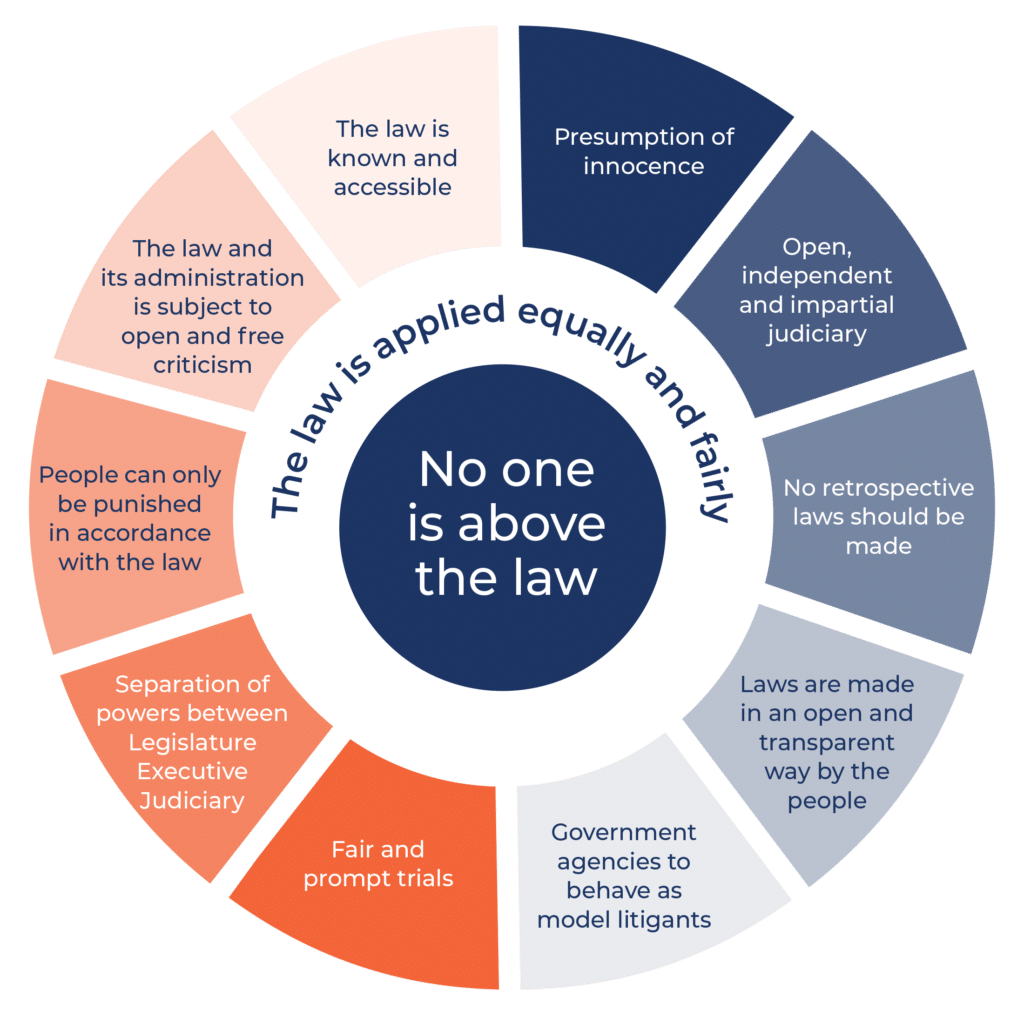

All this uncertainty creates significant problems for the rule of law. If a law cannot be readily knowable or ascertainable, states cannot adapt their behaviour and the law cannot be applied uniformly and fairly.

The United Nations, in its defence, acknowledged this problem back in 1947 when it created the International Law Commission to “consider[s] ways and means of making the evidence of customary international law more readily available”. Over the past seventy years the International Law Commission has made undeniable progress by attempting to ‘codify’ (record) customary international law.13 However this effort, by its nature, is retrospective and fleeting. Even if every aspect of customary international law were codified today, this would merely be a snapshot of opinio juris. As soon as state behaviour alters, which is inevitable given social and governmental change, opinio juris by definition will re-formulate. Any codification of opinio juris is therefore prone to go out of date and cause even greater confusion.

Indeed, even if there were a way to keep a written and accessible code completely up to date, this would actually serve to exacerbate the other negative trait of customary international law: it binds states without express consent.14

Consent and International Customary Law

It is commonly said that the international community is ‘anarchical’, in that there is no layer of higher government with absolute power to treat states like citizens. This is in a way unsurprising, since most states could (if pressed) rely solely on themselves for survival. States are thus in a position, unlike individual humans, to refuse the benefits and reciprocal responsibilities of participating in a community under law.

In recognition of this reality, it has long been a tenet of international law that a state must expressly consent to a rule (by, for example, signing a treaty) before it can be legally bound by the rule.

Customary international law not only upsets this idea of consent, it does it by stealth.

The ICJ, Consent, and Opinio Juris

At first, in some of its earliest decisions, the ICJ acknowledged the importance of consent when it suggested a state could exempt itself from an opinio juris rule if that state had expressly and repeatedly rejected the rule’s application from inception (“persistent objector”) (United Kingdom v.Norway15).

Soon thereafter, however, the ICJ reversed position and has since frequently ruled that states cannot opt out of customary international law either in full or in part. Opinio juris rules are instead equally and wholly binding on all states (North Sea Continental Shelf16, Canada/United States17), even in disputes where both sides believe otherwise (Nicaragua v. USA).18 The consent of the state is, quite clearly, not required.

Indeed, most worryingly, customary international law can render meaningless a state’s choice to join (or not join) a treaty, despite treaties being the most basic legal expression of a state’s consent. For, under the customary international law system, the widespread adoption of a treaty can be taken as evidence that the rules agreed to in that treaty are opinio juris – and therefore binding on all states regardless of whether they adopted the treaty itself (North Sea Continental Shelf).19 Opinio juris rules can even come from treaties that are not in force (Libya/Malta)20 and old discarded drafts of treaties (Libya/Tunisia 21). A state is not necessarily shielded even where it has adopted a different treaty that directly contradicts the opinio juris rule (Nicaragua v. USA22, North Sea Continental Shelf23, Costa Rica v. Nicaragua24).

Some opinio juris rules, in fact, go so far as to literally render treaties void. Called “jus cogens” (“compelling law”) and recognised by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), these are customs considered so fundamental and universally accepted (such as the prohibition of torture – Belgium v. Senegal25) that they can only be modified or superseded by a change in jus cogens itself (VCLT Article 53).Any part of a treaty that attempts to contravene a jus cogens rule is automatically invalid (VCLT Article 71), even if the treaty preceded the rule. Concerningly, for such a powerful concept, the ICJ has not provided clear criteria as to how jus cogens principles arise,26 even despite the International Law Commission acknowledging as far back as 1966 that the existence of jus cogens makes the idea of states’ consent “difficult to sustain”.27

Now it is true that it is the states themselves that allow this customary international law regime to continue. Legally speaking, were enough states willing to withdraw from or re-write the VCLT (and any other treaties like it), the states could dismantle the customary international law regime or at least give themselves greater power of consent. Instead the states have done the opposite – close to 2/3 of UN members have ratified the VCLT – and, ironically, the ICJ has deemed the VCLT itself to contain opinio juris and as such binding on all states (Costa Rica v. Nicaragua).28

Admittedly, therefore, it cannot be said that the customary international law regime is being forced wholesale on the states. The states did, at least to begin with, give their consent to exist under the customary international law regime in the first place. By failing to take that control back, the states have in a sense continued that consent.

What should worry proponents of the rule of law, though, is the poor quality of this continued consent. Given that opinio juris is not easy to measure or monitor accurately, it is difficult for states to give informed consent. Meanwhile, in the instances where opinio juris is clearly defined and therefore more easily invoked, the regime’s incrementalist nature (a decade being a “short period” of time even if new state behaviour is consistent and widespread (North Sea Continental Shelf)29) means a state can be ‘locked’ into those rules for as long as it takes for the rest of the international community to change behaviour. All the while, states do not have the luxury that humans do (in theory at least) of being able to move to jurisdictions with more agreeable laws.

Conclusion

Customary international law is, evidently, a troublesome issue for the rule of law. Few legal regimes claim the ability to ‘discover’ and apply amorphous laws to every state on the planet, no matter the ambiguous discretion involved and the inability of those on the receiving end to predict it. Fewer still can claim the ability to impose laws on states without express consent and in contradiction to international treaties.

To be sure, were customary international law in the hands of a universally-recognised judicial body with a well-defined mandate to use it, it would be a powerful legal tool in holding to account renegade states that create transnational problems and reject basic human ideals. But amidst the current reality, with supranational bodies worldwide in crises of legitimacy and the existing regime of international customary law opaque and non-consensual, it is one that international jurists today would be ill-advised to use.

Joshua Wood

NSWYL International Law Committee

Notes:

- Quoted GR Watson The Oslo Accords: International Law and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement 308 (Oxford University Press, 2000); cited in Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 47. ↩

- Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 101. ↩

- North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 3. at para 39, 77. ↩

- Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14 at para. 186. ↩

- Continental Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta) Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1985, p. 13, at para 27 ↩

- Wood, M. 2014, Second report on identification of customary international law, International Law Commission, Sixty-Sixth Session, Official Records of the General Assembly (A/CN.4/672) at para. 41. ↩

- Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v.United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14, at para. 176, 194, 237. ↩

- Dispute regarding Navigational and Related Rights (Costa Rica v. Nicaragua), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2009, p. 213. at para 144. ↩

- Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 36. ↩

- Kammerhofer, J 2011 Uncertainty in International Law: A Kelsenian perspective, Routledge, p.72. ↩

- Lepard, BD 2010 Customary International Law: A New Theory with Practical Applications, Cambridge University Press, p. 31. ↩

- Kammerhofer, J 2011 Uncertainty in International Law: A Kelsenian perspective, Routledge p. 78-80. ↩

- Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 36, 57-59. ↩

- Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 40. ↩

- Fisheries case, Judgment of December 18th, 1951: I.C.J. Reports 1951, p. 116 at p. 131; cited in Lepard, BD 2010 Customary International Law: A New Theory with Practical Applications, Cambridge University Press, p. 37 and in Gunaratne R 2008, ‘Anglo Norweigan Fisheries Case (Summary on Customary Law)’ Public International Law, web log post, 22 April 2011, viewed 31 January 2017, https://ruwanthikagunaratne.wordpress.com/tag/persistent-objector/ ↩

- North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 3. at para 63. ↩

- Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Gulf of Maine Area, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1984, p. 246. ↩

- Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14 at para. 184. ↩

- North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 3. at para 63 ↩

- Continental Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta) Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1985, p. 13, at para 26-27. ↩

- Continental Shelf (Tunisia/Libyan Arab Jamahiriya), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1982, p. 18 at para. 49, 109; cited in Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 37. ↩

- Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14 at para 174-175 ↩

- North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 3. at para 63-65. ↩

- Dispute regarding Navigational and Related Rights (Costa Rica v. Nicaragua), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports

2009, p. 213. at para 35-36. ↩ - Questions relating to the Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite (Belgium v. Senegal), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2012, p 422. at para. 99. ↩

- Rosenne, S 2004 The Perplexities of Modern International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 361-363. ↩

- International Law Commission, 1966, Report of the of the International Law Commission on the work of its Eighteenth Session, 4 May – 19 July 1966, Official Records of the General Assembly, Twenty-first Session, Supplement No. 9 (A/6309/Rev.1) at page 247. ↩

- Dispute regarding Navigational and Related Rights (Costa Rica v. Nicaragua), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2009, p. 213, at para. 47. ↩

- North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 3. at para 74. ↩